From the Mainland to the Islands: A Taíno Genesis

The story of the Taíno begins not in the Caribbean islands, but in the heart of South America. As speakers of an Arawakan language, their ancestors originated in the Orinoco River delta region of modern-day Venezuela. Around 2,500 years ago, they began a remarkable maritime migration. Using massive dugout canoes that could hold dozens of people, they journeyed north, island by island, through the Lesser Antilles and into the Greater Antilles—the islands we now know as Cuba, Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico, and Jamaica.

By the time Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492, the Taíno had established a vast network of communities across these islands. They were not a monolithic empire but a collection of independent chiefdoms, bound by a common language, culture, and trade. They were the dominant culture of the Greater Antilles, having displaced or absorbed earlier peoples, and they occasionally clashed with the Kalinago (Caribs) of the Lesser Antilles.

A Society of Chiefs, Nobles, and Spirit

Taíno society was far from the “primitive” caricature painted by early European chroniclers. It was a well-organized hierarchy led by a chief, or cacique. This position, which could be held by both men and women, was often inherited matrilineally, passing through the mother’s family line—a detail that astonished the patriarchal Europeans.

The social structure was divided into three main tiers:

- Nitaínos: The noble class, which included the caciques and their families. They were the political, military, and religious leaders.

- Naborias: The vast majority of the population, who were the commoners responsible for farming, fishing, and crafting.

- Bohiques: The shamans or priests, who were respected healers and mediators between the physical and spiritual worlds.

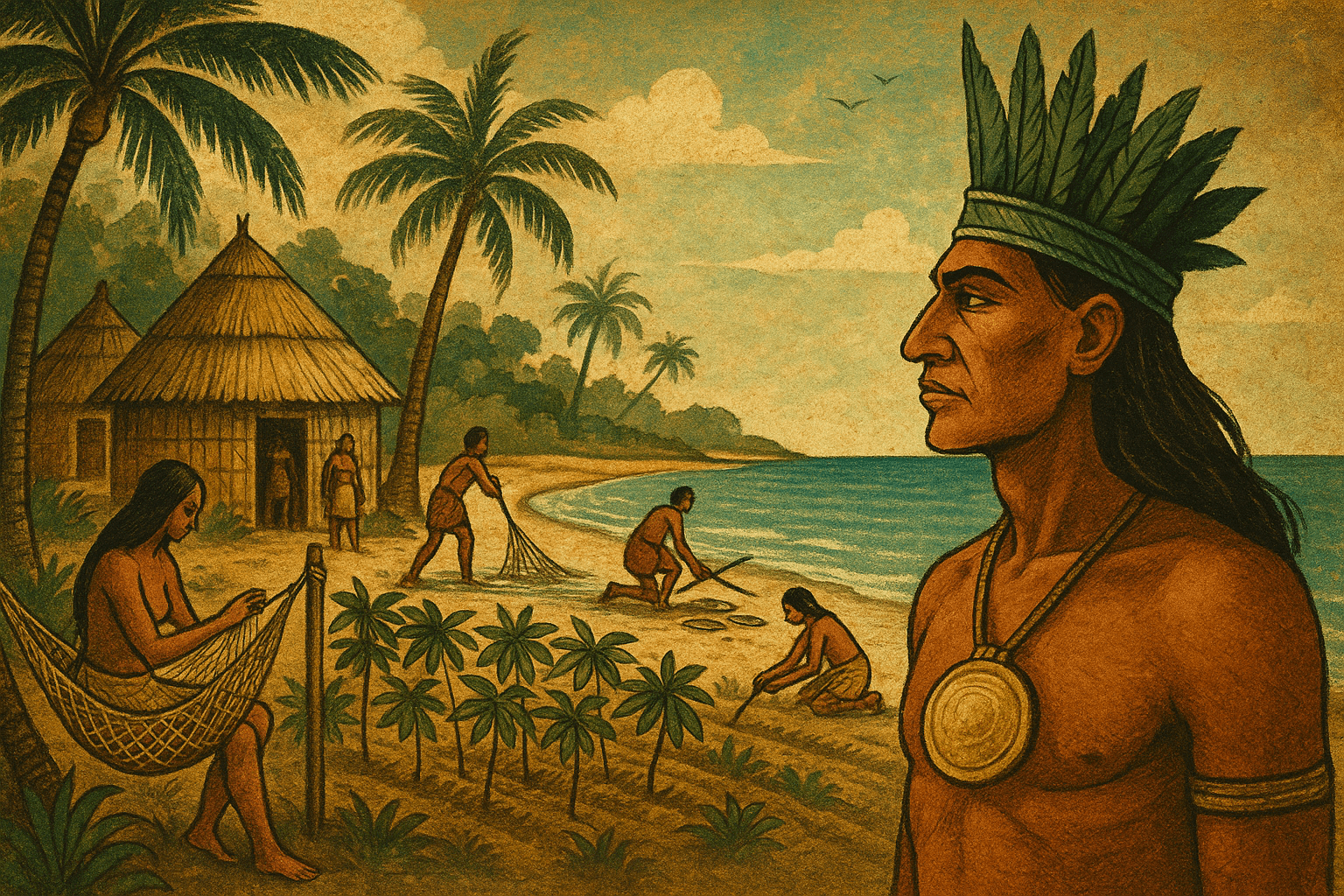

Life centered around villages called yucayeques. These were often built around a central plaza, the batey, which served as a space for public ceremonies, dances, and a ceremonial ball game. Homes were impressive feats of architecture, primarily the circular bohío for commoners and the larger, rectangular caney for the cacique, all built from wood and thatch with remarkable durability against the region’s hurricanes.

Life, Sustenance, and the Sacred

The Taíno were master agriculturalists. Their primary innovation was the conuco, a raised mound of earth that improved drainage, prevented soil erosion, and increased crop yields. This brilliant technique allowed them to cultivate a rich variety of foods, most importantly yuca (cassava). They knew how to process this poisonous root into a safe, nutritious flour to make cassava bread, a staple of their diet. Other vital crops included maize (corn), sweet potatoes, beans, peppers, peanuts, and tobacco, which they smoked in pipes for both recreation and ritual.

Spirituality permeated every aspect of Taíno life. Their universe was populated by deities and ancestral spirits known as zemís (or cemís). These were not just abstract concepts; they were physically represented in intricately carved objects made of wood, stone, bone, or cotton. The two principal deities were Yúcahu, the great spirit of creation, cassava, and the sea, and his mother Atabey, the goddess of fresh water, fertility, and childbirth.

The areíto was the ultimate expression of their communal and spiritual life. It was a grand ceremony of song, dance, and oral history, where the community recounted its myths, legends, and major events, ensuring their culture was passed down through generations.

The Cataclysm of 1492

The arrival of Christopher Columbus’s three ships in the Bahamas on October 12, 1492, marked the beginning of the end for the Taíno world as it had existed for centuries. The initial encounters were filled with curiosity. The Taíno, possessing a culture rooted in hospitality, generously shared their food and resources. Columbus, in his own journals, noted their peaceful nature and lack of iron weapons, remarking how easily they could be “subjugated and made to do all that one wished.”

This observation quickly turned into a brutal policy. The Spanish obsession with gold led to the establishment of the encomienda system, a grant of Taíno labor to Spanish colonists that was, in effect, slavery. The Taíno were forced into mines and fields, overworked, and subjected to horrific cruelty. Those who resisted were met with overwhelming military force.

Leaders like the fierce Caonabó and the revered female cacique Anacaona on Hispaniola led valiant, but ultimately doomed, uprisings. Yet, the deadliest weapon the Europeans brought was not the sword, but disease. Smallpox, measles, and influenza, to which the Taíno had no immunity, swept through the islands with catastrophic speed. Within a few decades of contact, the Taíno population plummeted by an estimated 80-90%—one of the most devastating demographic collapses in human history.

Legacy and Reawakening

For centuries, the official history was that the Taíno had been completely wiped out. This narrative of extinction, however, is a simplification. While their society and political structures were shattered, their people were not entirely erased. Many Taíno, particularly women, survived by intermarrying with Spanish colonists and enslaved Africans, creating the foundation of the modern Caribbean population. Their DNA, their knowledge, and their culture lived on, woven into the very fabric of an evolving Creole society.

Their influence is still present in our everyday language. Words you may use without a second thought have Taíno roots, including:

- barbecue (barbacoa)

- hammock (hamaca)

- hurricane (hurakán)

- canoe (canoa)

- tobacco (tabaco)

- iguana (iwana)

Today, a powerful Taíno revival is underway. Across Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and the diaspora, descendants are reconnecting with their indigenous ancestry. Through genetic research, cultural reclamation, and political advocacy, they are challenging the extinction myth and proudly asserting their identity. The story of the Taíno is no longer just one of tragedy; it is a story of profound resilience and the enduring power of a people who were the first to call the Caribbean home.