In the grand tapestry of world history, some threads are vibrant and well-documented, while others are frayed, mysterious, and known more by the chaos they wrought than by their own story. Into this latter category fall the Hephthalites, a ghost-like confederation of nomads who thundered out of the Central Asian steppes in the 5th and 6th centuries. Dubbed the “White Huns” by contemporary writers, they were a force of nature that humbled the mighty Sasanian Empire of Persia and broke the back of India’s celebrated Gupta Empire, forever altering the political landscape of Asia.

The Enigma of the “White Huns”

Who exactly were the Hephthalites? This question has puzzled historians for centuries. Unlike the Huns of Attila who terrorized Europe a generation earlier, the Hephthalites remain shrouded in mystery. The name “White Huns” is itself a clue and a puzzle. Roman historian Procopius noted that they were not racially akin to Attila’s Huns, describing them as having fair skin and more “civilized” features. This has led to speculation that the “white” might refer to a royal or elite color, rather than skin tone.

Their origins are a subject of intense debate. Chinese sources, such as the Book of Wei, suggest they originated in the Altai Mountains and were possibly of Turkic or proto-Mongolic stock. Persian and Indian accounts, however, often associate them with Iranic peoples from the eastern fringes of the Persian world. Their language is lost, and what little we know of their culture comes from coinage and the biased accounts of their enemies. They seem to have been a culturally diverse confederation, practicing a mix of Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, and Zoroastrianism, absorbing the traditions of the lands they conquered.

Unlike many nomadic groups, the Hephthalites established urban centers, with their capital at Badiyan, near modern-day Kunduz in Afghanistan. They were not just raiders; they were empire-builders, creating a vast but short-lived kingdom that stretched from the Caspian Sea to the Tarim Basin and deep into India.

A Storm from the East: Hephthalite Military Prowess

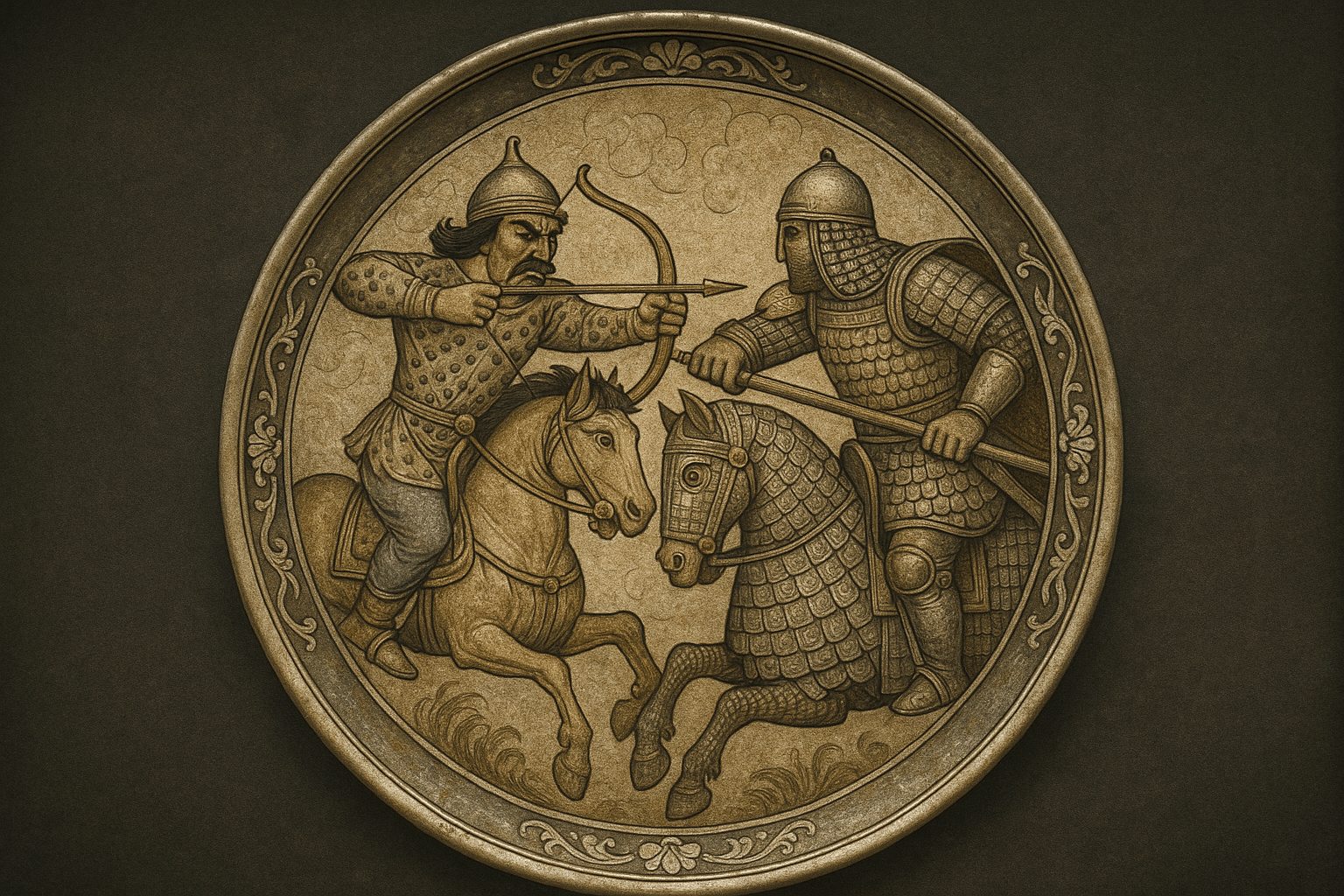

The Hephthalites’ success was built on a fearsome and effective military machine. While their “Hun” moniker evokes images of light horse archers, the Hephthalites represented an evolution in steppe warfare. Their elite warriors were heavily armored cataphracts—both horse and rider encased in lamellar armor—wielding long lances and swords. This shock cavalry was supported by masses of highly skilled horse archers armed with powerful composite bows.

Their tactical genius lay in combining these elements with classic nomadic strategies:

- Feigned Retreats: They were masters of luring disciplined armies into disorganized pursuit, only to turn and annihilate them with a storm of arrows and a decisive cavalry charge.

- Psychological Warfare: Their reputation for ferocity preceded them. They cultivated an image of unstoppable cruelty, which often caused opposing forces to break before a battle was even truly joined.

- Ambushes and Deception: They used their knowledge of the terrain to their advantage, setting elaborate traps for armies unused to the open steppes or rugged mountains of Central Asia.

This military system proved devastatingly effective against the more traditional armies of Persia and India, which relied on masses of infantry and slow-moving war elephants—perfect targets for the mobile Hephthalite warriors.

The Hammer of Persia: Clashing with the Sasanians

The Sasanian Empire, one of the two superpowers of the late antique world, was the first great power to feel the full force of the Hephthalite storm. In the mid-5th century, the Sasanian king Yazdegerd II fought inconclusive wars against them. His successor, Peroz I, was obsessed with crushing the Hephthalite threat once and for all.

It was a fatal obsession. In his first major campaign, around 469 CE, Peroz was defeated and captured, forced to suffer the humiliation of paying a massive ransom and leaving his son as a hostage. Burning for revenge, Peroz gathered a massive army and marched east again in 484 CE. The Hephthalite king, Akhshunwar, laid a masterful trap. He had his army dig a vast, camouflaged ditch across the plains where the battle would take place. Luring the charging Sasanian cataphracts forward, the Hephthalites feigned a retreat. The Persian heavy cavalry, blinded by dust and arrogance, plunged headlong into the hidden trench. The result was an unmitigated disaster. Peroz I was killed, his army was annihilated, and the Sasanian court was thrown into chaos. For years afterward, Persia was forced to pay a crippling annual tribute, effectively becoming a Hephthalite vassal state.

The Fall of a Golden Age: The Hephthalites in India

While the Sasanians were being humbled, another branch of the Hephthalites, known in India as the Hunas, turned their attention south towards the wealthy Gupta Empire. At the time, Gupta India was enjoying a “Golden Age” of peace, prosperity, and cultural achievement. The first wave of invasions in the 460s was successfully repulsed by the heroic Gupta emperor Skandagupta, but the effort exhausted the imperial treasury.

By the end of the 5th century, a new wave of Hephthalite invaders under a leader named Toramana broke through the Gupta defenses. Toramana established a powerful kingdom in northern and central India. His son, Mihirakula, who came to power around 515 CE, earned a horrifying reputation. Buddhist sources portray him as a monstrous tyrant, a “demon of destruction” who razed monasteries, slaughtered monks, and reveled in cruelty. While likely exaggerated, these accounts reflect the profound shock and terror the Hephthalite invasion inspired.

Although an alliance of Indian princes eventually defeated Mihirakula around 528 CE, the damage was done. The constant warfare had drained the Gupta Empire of its wealth and authority. The invasions shattered the imperial unity, allowing local rulers to break away. The Hephthalites did not conquer India, but they effectively administered the killing blow to its last great classical empire, plunging the subcontinent into a period of political fragmentation.

An Alliance of Enemies: The Final Downfall

Like a meteor, the Hephthalite Empire burned brightly but briefly. Their downfall came not from a single enemy, but from an unholy alliance of two rising powers that caught them in a pincer movement. To the west, the Sasanian Empire had recovered its strength under the legendary king Khosrow I. To the east, a new nomadic power was on the rise: the Göktürks.

Seeing a common enemy and a chance to seize valuable territory, the Persians and the Turks formed a temporary pact. Around 560 CE, they launched a coordinated two-front war. The Göktürks smashed the Hephthalite forces from the east, while Khosrow’s army advanced from the west. In a series of decisive battles, most notably near Bukhara, the Hephthalite confederation was shattered. Their last king was killed, and their vast territory was carved up between the victorious Persians and Turks. The Hephthalites as a political entity vanished from history, their people absorbed into the local populations of Central Asia.

Though their own voices are lost, the Hephthalites left an indelible mark on the world. They were the scourge of empires, a catalyst for change whose violent passage brought one golden age to an end and fatally weakened another ancient superpower. They remain a potent reminder of how swiftly and decisively the nomadic peoples of the steppe could reshape history.