This is not just a collection of myths, but a complex system of governance that transformed a landscape of bloodshed into one of cooperation and stability. It’s a story of visionaries, intricate political structures, and a philosophy that sought to create a peace that would last for generations.

A Time of Endless War

To understand the revolutionary nature of the Great Law, we must first picture the world it replaced. Before the confederacy was formed (sometime between the 12th and 15th centuries), the five nations—the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca—were locked in a brutal and seemingly endless cycle of violence. Blood feuds were the norm, where a single killing would trigger a cascade of retaliatory attacks that could span decades. Mourning was constant, and fear was a way of life. It was a dark time, where trust between nations was nonexistent and every neighbor was a potential enemy.

The Legend of the Great Peacemaker

Into this chaos came a prophet known as the Great Peacemaker. According to oral tradition, he was born of a virgin mother and came from the north, traveling in a white stone canoe. His mission was simple yet profound: to replace the cycle of violence with reason, justice, and peace. “The Creator is sad that he sees human beings, his creations, killing one another”, he taught.

The Peacemaker was not alone. He soon allied with two other crucial figures:

- Hiawatha (Ayenwatha): An Onondaga man (some traditions say Mohawk) consumed by grief after losing his daughters in the ongoing wars. He was a powerful but tormented figure. The Peacemaker “combed the snakes” of grief and rage from Hiawatha’s hair with words of condolence, restoring his sanity. As a gifted orator, Hiawatha became the Peacemaker’s spokesperson, carrying the message of peace to the five nations.

- Jigonhsasee (the Mother of Nations): A Seneca woman who was a leader in her own right. She was the first to accept the Peacemaker’s message, and her endorsement gave the mission critical legitimacy. By accepting his vision, she secured a foundational role for women in the new political structure.

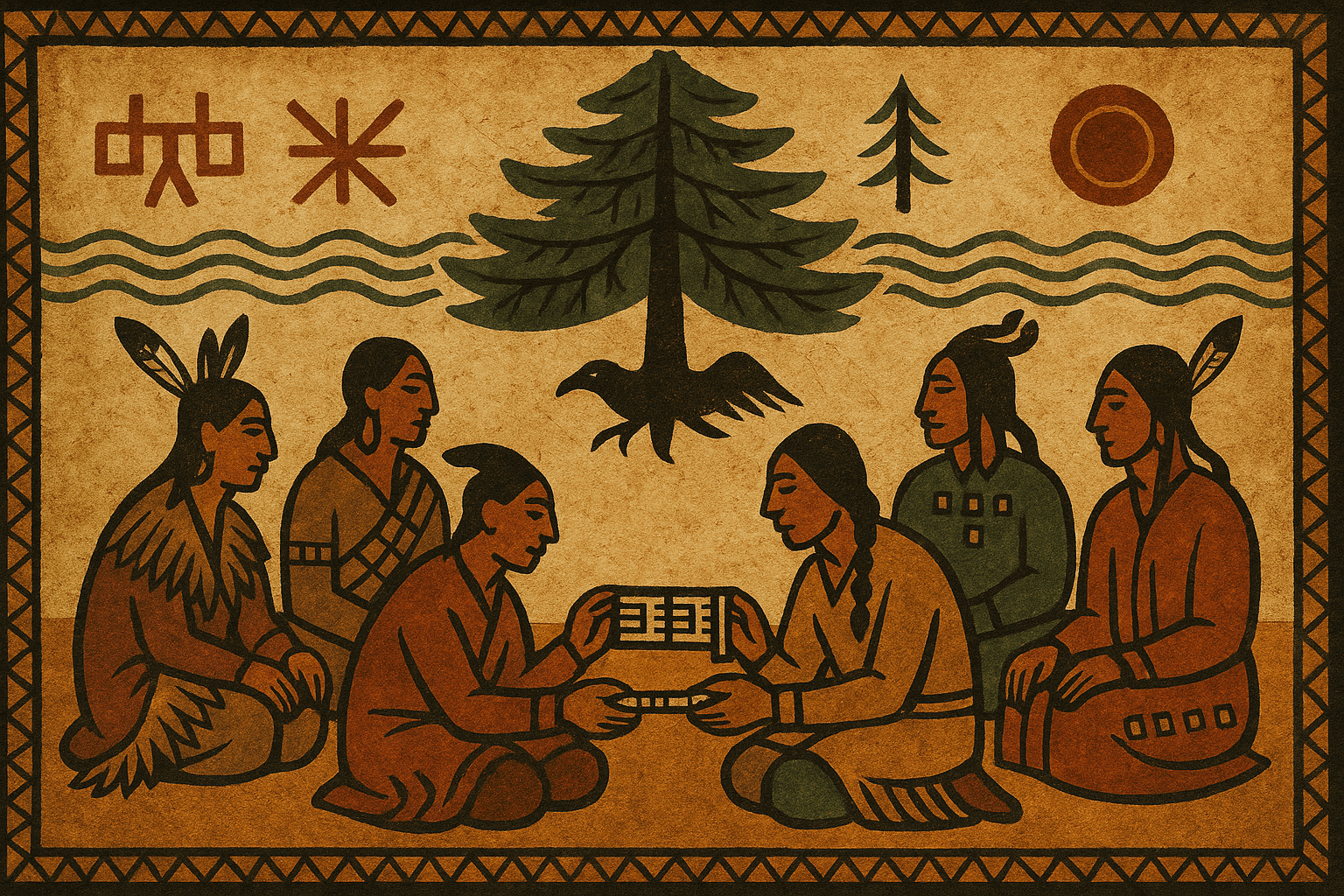

Together, they traveled from nation to nation, sharing the vision of a grand council where all nations would have a voice and disputes would be settled through deliberation, not war.

Uniting the Five Nations

The process of unification was not easy. The final and most formidable obstacle was the Onondaga chief, Atotarho (Tadodaho). He was a powerful sorcerer so twisted by hate and rage that his body was contorted and his hair was a writhing mass of snakes. He represented the chaos and violence of the old ways. He rejected the message of peace multiple times.

The Peacemaker, Hiawatha, and the leaders of the now-convinced nations confronted Atotarho not with weapons, but with the combined power of their peaceful message. They sang songs of peace and, in a powerful symbolic act, combed the snakes from his hair, straightened his body, and offered him a new purpose. They made him the “Firekeeper”—the chairperson of the Grand Council of Chiefs, responsible for moderating debates and ensuring the law was followed. By transforming their greatest enemy into a cornerstone of the new order, they demonstrated the true power of their philosophy.

With all five nations united, the Peacemaker symbolically uprooted a great white pine tree, the Tree of Peace. The leaders of the five nations threw their weapons of war into the chasm below, and the Peacemaker replanted the tree. Its white roots of peace spread out in the four cardinal directions, inviting other nations to follow the roots and find shelter under its branches. An eagle was placed at the top, to watch for any dangers to the peace.

The Pillars of the Great Law of Peace

The Great Law was far more than a simple peace treaty. It was a comprehensive constitution that established a federal system with clear roles, responsibilities, and a system of checks and balances that is strikingly familiar to modern eyes.

A Bicameral Legislature

The Grand Council of 50 chiefs (sachems) was divided into two “houses”:

- The Elder Brothers: The Mohawk and Seneca chiefs would debate an issue first.

- The Younger Brothers: The Oneida and Cayuga chiefs would then debate the same issue.

If both houses agreed, their decision was passed to the Onondaga, the “Firekeepers”, for final confirmation. This structure ensured that every decision was thoroughly vetted and required broad consensus, preventing any single nation from dominating the others.

The Power of the Clan Mothers

One of the most radical aspects of the Great Law was the power it vested in women. The Haudenosaunee are a matrilineal society, meaning lineage is traced through the mother. The Clan Mothers, elder women of each clan, held immense authority. They were responsible for:

- Selecting the male chiefs who would represent their clan in the Grand Council.

- “De-horning” or deposing a chief who ignored their warnings, stripping him of his title and authority.

– Warning chiefs up to three times if they failed to represent the people’s interests or abide by the Great Law.

This gave women ultimate control over the government, ensuring that leaders remained accountable to the people they served—a democratic principle of profound importance.

Individual Liberty and Unity

The Great Law guaranteed freedom of speech and religion. While the Confederacy acted as one on matters of war and international policy, each nation retained sovereignty over its own internal affairs. The symbol of the confederacy was five arrows bound together, representing the idea that while a single arrow is easily broken, five bound together are unbreakable. It was a potent metaphor for federalism: strength through unity, without sacrificing individual identity.

A Legacy Etched in History

The Great Law of Peace created a stability that allowed the Haudenosaunee to become the dominant political and military power in the northeastern woodlands for centuries. Its influence didn’t stop there. American colonists, including Benjamin Franklin and other founding fathers, directly interacted with Haudenosaunee leaders and observed their council proceedings. The concepts of federalism, separating powers, and ensuring leaders are servants of the people resonated deeply.

In 1988, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution formally acknowledging the historical debt that the U.S. Constitution owes to the Iroquois Confederacy. While not a direct copy, the Great Law of Peace served as a real-world example of a united, democratic republic in action, proving that such a government was possible.

Today, the Great Law of Peace is a living tradition, still guiding the Haudenosaunee people. It stands as a powerful testament to the political genius of Indigenous peoples and serves as a timeless model for achieving peace, justice, and a government truly of, by, and for the people.