A Voyage Tarnished by Greed and Grudge

The Batavia was the pride of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), a brand-new flagship on her maiden voyage from the Netherlands to the bustling port of Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies. She was laden with a fortune in silver coins and priceless jewels, intended for trade. Aboard were over 300 people: sailors, soldiers, wealthy merchants, and their families.

But beneath the decks, a toxic conspiracy was brewing. The two men in charge, Commander Francisco Pelsaert and Skipper Ariaen Jacobsz, despised each other. Pelsaert was a high-ranking VOC official, an administrator out of his depth at sea, while Jacobsz was a rough, experienced mariner who resented Pelsaert’s authority. Into this volatile mix stepped Jeronimus Cornelisz, an apothecary and bankrupt merchant fleeing his homeland under a cloud of heretical scandal.

Cornelisz was a charismatic psychopath. A follower of a controversial painter, he held twisted beliefs that the enlightened man was free from sin and moral law. He saw the tension between the commander and skipper as an opportunity. He quietly allied with Jacobsz and began plotting a mutiny. Their plan was simple and savage: seize the ship, murder those loyal to the VOC, and sail away with the treasure to start a new life as pirates.

Wreck on Batavia’s Graveyard

Before their mutiny could be launched, fate intervened. On the moonless night of June 4, 1629, while Skipper Jacobsz was on watch, the Batavia slammed into a coral reef in the Houtman Abrolhos, a treacherous archipelago approximately 40 miles off the coast of Western Australia. The magnificent ship began to break apart, sending its passengers and crew scrambling for their lives.

Roughly 280 survivors managed to get ashore, huddled on a series of small, barren coral islands that offered no food, no shelter, and most terrifyingly, no fresh water. The islands would later be grimly named “Batavia’s Graveyard.”

A Desperate Search and a Power Vacuum

Faced with certain death from thirst, Commander Pelsaert made a desperate decision. He, Skipper Jacobsz, and about 40 others piled into the ship’s longboat. After a futile search for water on the Australian mainland, they undertook an astonishing feat of navigation, sailing the open boat for over 2,000 miles to Batavia to summon help. They made it in 33 days, an incredible achievement in its own right.

Back on the islands, however, their departure created a deadly power vacuum. With Pelsaert gone, the highest-ranking VOC official left was the undermerchant: Jeronimus Cornelisz. The failed mutiny now had a second chance, not on a ship, but on an island prison.

The Reign of Terror

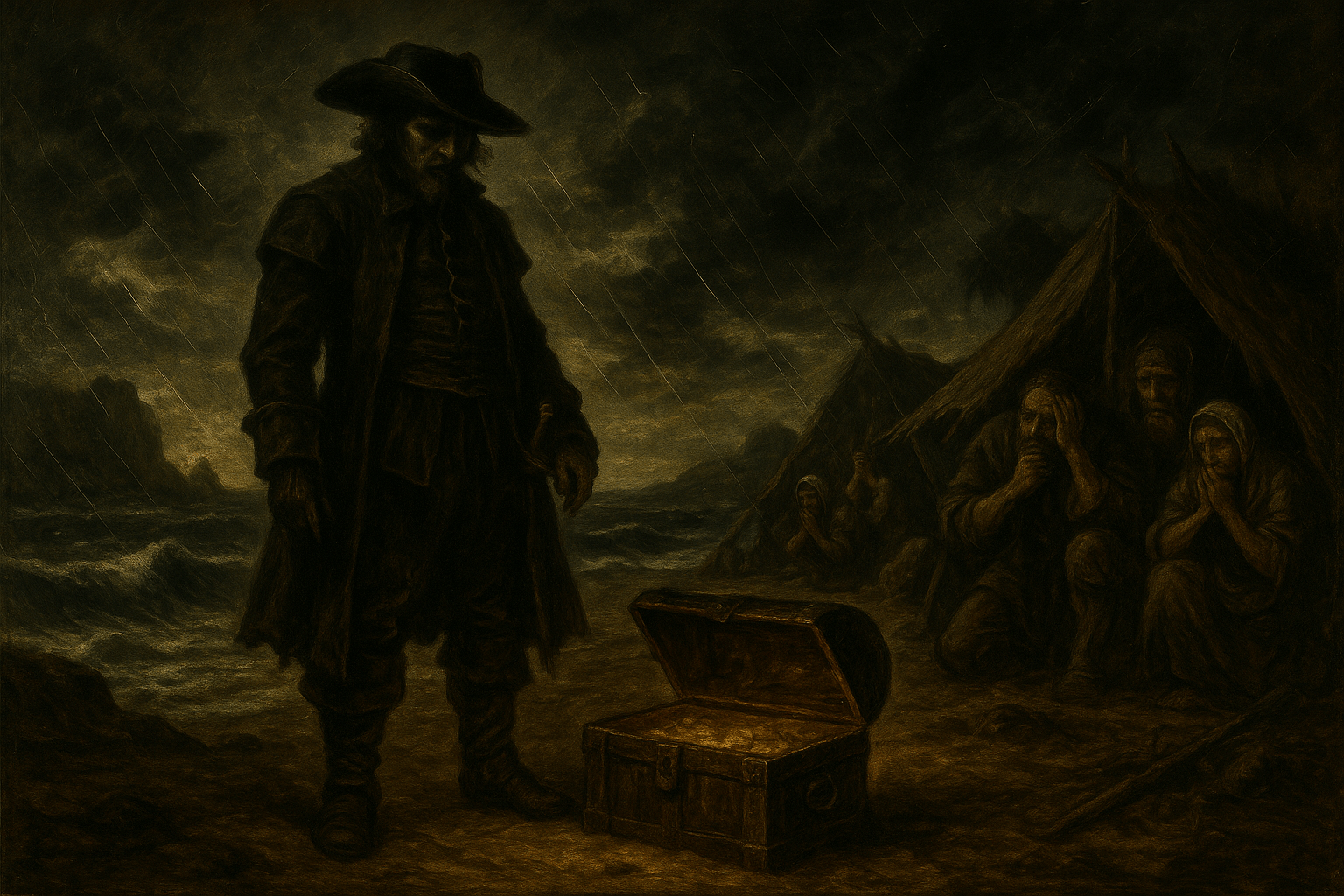

Cornelisz quickly established his authority. He gathered the mutineers and seized all the salvaged weapons and food supplies. His twisted philosophy was now law. He declared a new society free from rules, where only the strong, led by him, would survive. What followed was a systematic campaign of terror and murder.

His methods were chillingly calculated:

- Eliminating Threats: Anyone who might challenge him or who was loyal to Pelsaert was marked for death. Healthy men were sent on fabricated missions to other islands to search for water, only to be abandoned or ambushed and murdered.

- Conserving Resources: The sick and the weak were the first to be killed, drowned or bludgeoned to death under the pretense of “mercy.”

- Instituting Sexual Slavery: Cornelisz seized the surviving women, forcing them into sexual servitude for himself and his top henchmen. The fate of Lucretia van der Mijlen, a high-born young woman whom Cornelisz claimed exclusively for himself, became a symbol of the horror. Anyone who resisted was executed.

Over two months, Cornelisz and his band of killers murdered at least 110 men, women, and children. The islands became a landscape of fear, where a knock on your tent flap could mean a blade at your throat.

The Resistance of Wiebbe Hayes

Cornelisz’s one miscalculation was a soldier named Wiebbe Hayes. Early on, Cornelisz had dispatched Hayes and his group of soldiers to a neighboring island (now West Wallabi Island) to search for water, fully expecting them to perish. He wanted them out of the way before the massacres began.

But against all odds, Hayes a hero. They did what no one else could: they found wells of fresh water and a food source in the local population of small kangaroos (tammar wallabies). When terrified survivors began fleeing Cornelisz’s “Murder Island” on makeshift rafts, they brought Hayes news of the ongoing slaughter.

Hayes, a common soldier thrust into a leadership role, organized his men. They fashioned crude weapons from salvaged materials and built small, defensive forts from limestone rock. When Cornelisz, realizing his intended victims were now a threat, launched attacks, Hayes’s outnumbered but disciplined group fought them off in a series of desperate battles.

Rescue and Retribution

On September 17, a sail appeared on the horizon. It was Pelsaert, returning with the rescue ship Sardam. A frantic race ensued. Cornelisz’s men made one last, desperate charge to overwhelm Hayes’s group so they could be the first to meet the rescuers with a fabricated story of survival. But Hayes and his men won the race, reaching the Sardam first and frantically informing a horrified Pelsaert of the atrocities.

Justice was swift and brutal. Pelsaert, armed with the authority of the VOC, held a court on the islands. The worst of the mutineers were tortured to extract confessions. Jeronimus Cornelisz and his main conspirators had their hands amputated before being hanged. Two lesser mutineers were marooned on the Australian mainland, becoming the continent’s first, albeit unwilling, European inhabitants. Their ultimate fate remains unknown.

The Legacy of the Batavia

The story of the Batavia is a chilling reminder of the fragility of human civilization. Once the structures of authority and society were stripped away, what emerged was not a noble struggle for survival, but a terrifying glimpse into the abyss of human cruelty. The discovery of the shipwreck in 1963, and the subsequent archaeological excavation of the mutineers’ island graves, has confirmed the horrifying details of the historical accounts.

The tale serves as a permanent historical marker—a story of how, in the absence of order, one man’s dark charisma was enough to turn a group of desperate survivors into a death cult on a deserted shore.