Who Were the ‘Cloud People’?

The Zapotec civilization emerged around 500 BCE, making them contemporaries of Classical Greece and one of the earliest complex societies in Mesoamerica. The name “Cloud People” likely refers not to a celestial origin, but to their primary settlements located high in the temperate valleys of Oaxaca’s central mountain range. From these strategic highlands, they controlled trade routes, farmed the fertile valley floors, and built one of ancient America’s most spectacular cities.

Unlike the later Aztec Empire, which was a multi-ethnic tributary state, the Zapotecs were a more homogenous society organized into a confederation of city-states. At the heart of this confederation, acting as its political and religious nucleus for nearly 1,500 years, was the magnificent city of Monte Albán.

Monte Albán: The Acropolis of Mesoamerica

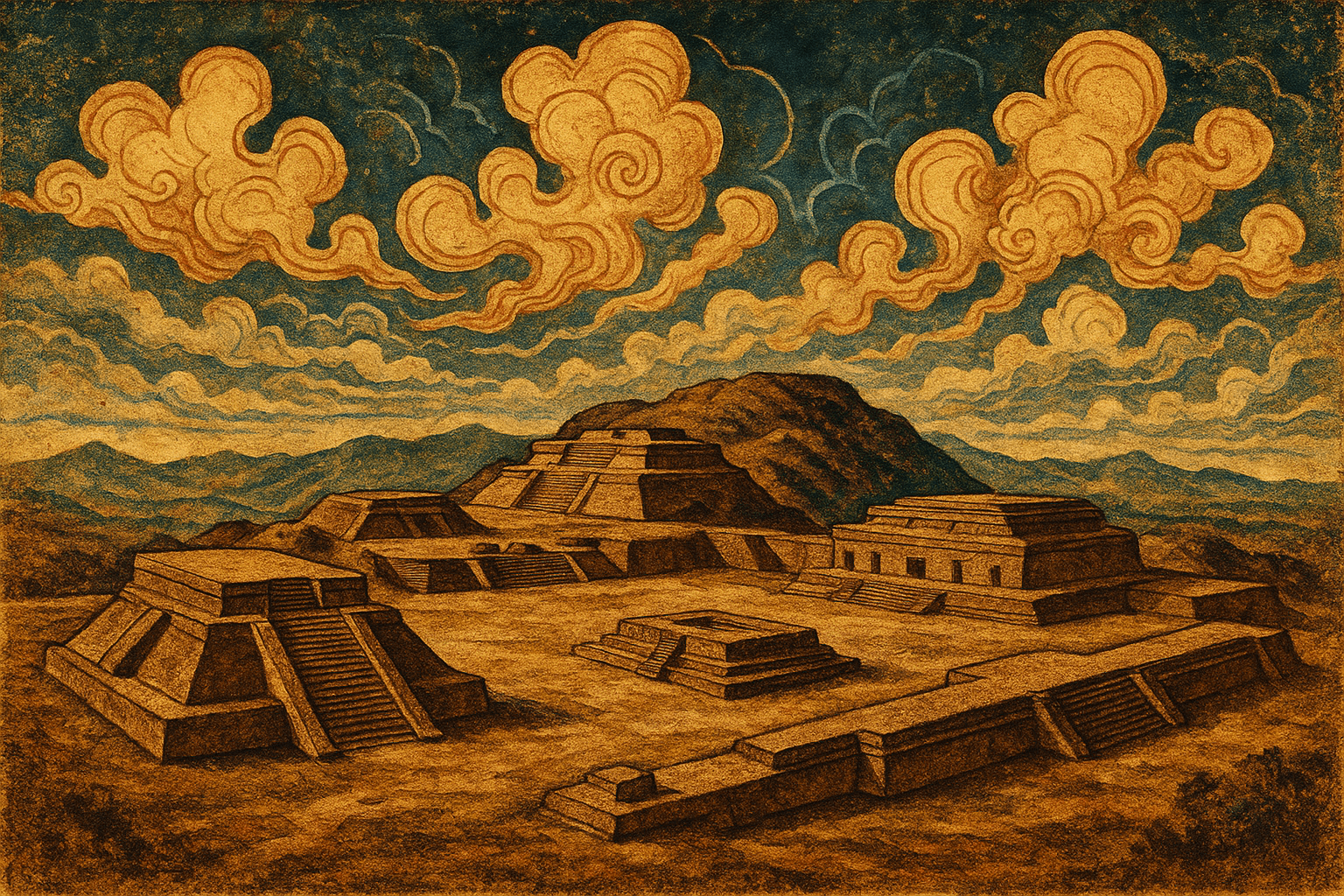

Perched atop a 1,300-foot-high artificially flattened mountain, Monte Albán is a breathtaking feat of engineering. It wasn’t just a city; it was a statement. With panoramic views of the entire Valley of Oaxaca, it was the undisputed center of the Zapotec world. The heart of the city is the Great Plaza, a massive rectangular space flanked by pyramidal temples, palaces, and a ball court.

Among its most fascinating and enigmatic features are the stone slabs known as the danzantes (“dancers”). These carved figures, dating to the city’s earliest period, depict nude figures in contorted, almost pained poses. Initially thought to be shamans or dancers in ecstatic ritual, scholars now largely believe they represent slain and mutilated captives from rival groups. The glyphs carved alongside them—some of the earliest examples of writing in Mesoamerica—name the individuals or the places they came from, serving as a stark monument to Monte Albán’s military might.

The city also reveals the Zapotecs’ advanced understanding of astronomy. One peculiar, arrow-shaped structure known as Building J is oriented differently from all other buildings on the plaza. Its alignment corresponds to key astronomical events, such as the rising of the star Capella, functioning as a sophisticated observatory.

A Language Written in Stone

The Zapotecs were pioneers of writing. Their hieroglyphic script is one of the oldest in the Americas, predating even the Classic Maya script. While not yet fully deciphered, scholars can understand key elements, particularly those related to the calendar and the names of rulers and places. The Zapotecs, like other Mesoamerican cultures, utilized a sophisticated calendrical system composed of two interlocking cycles:

- The Pije: A 260-day ritual calendar used for divination and naming individuals.

- The Yza: A 365-day solar calendar that governed agricultural cycles.

These two calendars would align every 52 years, marking a significant cycle in the Zapotec worldview. Inscriptions found on stelae, tomb walls, and the danzantes themselves record important dates, royal lineages, and military conquests, giving us a fragmented but compelling glimpse into their history.

Cities of the Dead: Tombs and Ancestor Veneration

Perhaps no aspect of Zapotec culture is more stunning than their funerary traditions. The Zapotecs held a deep reverence for their ancestors, who were seen as active intermediaries between the living and the gods. Elite families constructed elaborate, subterranean tombs beneath their palaces and residences, creating literal “cities of the dead” that mirrored the world of the living.

These tombs were not just burial pits but multi-room stone chambers, their walls often covered in vibrant frescoes. The murals depict processions of gods, family members making offerings, and a pantheon of deities, most notably Cocijo, the powerful god of lightning and rain, easily identified by his jaguar-like snout and forked tongue.

The most spectacular discovery came in 1932, when Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso excavated Tomb 7 at Monte Albán. The tomb, a treasure trove rivaling that of Tutankhamun in its cultural significance, held the remains of a high-status individual accompanied by an astonishing collection of over 500 objects. These included exquisitely crafted gold pectorals, masks inlaid with turquoise, delicately carved jaguar bones, and necklaces of pearl and jade. The find revealed the immense wealth commanded by the Zapotec elite and their mastery of metallurgy and stonework.

From Decline to Endurance

Around 800 CE, Monte Albán began a process of gradual decline and abandonment. The reasons are still debated but likely involve a combination of political fragmentation, environmental strain, and the rise of other powerful centers in the region. However, the Zapotecs did not disappear. Their political focus shifted to new city-states like Mitla.

Mitla, which rose to prominence after Monte Albán’s fall, is famous for its unique and magnificent architecture. Instead of grand pyramids, its palaces are adorned with intricate geometric mosaics made from thousands of individually cut and polished stones, a style of fretwork found nowhere else in Mesoamerica. It stands as a testament to the evolution and continued creativity of Zapotec culture.

The Zapotecs fiercely resisted domination by both the expanding Aztec Empire and, later, the Spanish conquistadors. While eventually subdued, their culture proved resilient. Today, Zapotec people constitute one of the largest and most vibrant indigenous groups in Oaxaca. Zapotec languages are still spoken throughout the state, ancient weaving and pottery traditions are passed down through generations, and the spirit of the Binnizá lives on in the marketplaces, festivals, and communities of their ancestral homeland. The “Cloud People” may no longer rule from mountaintop cities, but their legacy is anything but ancient history—it is a living, breathing part of modern Mexico.