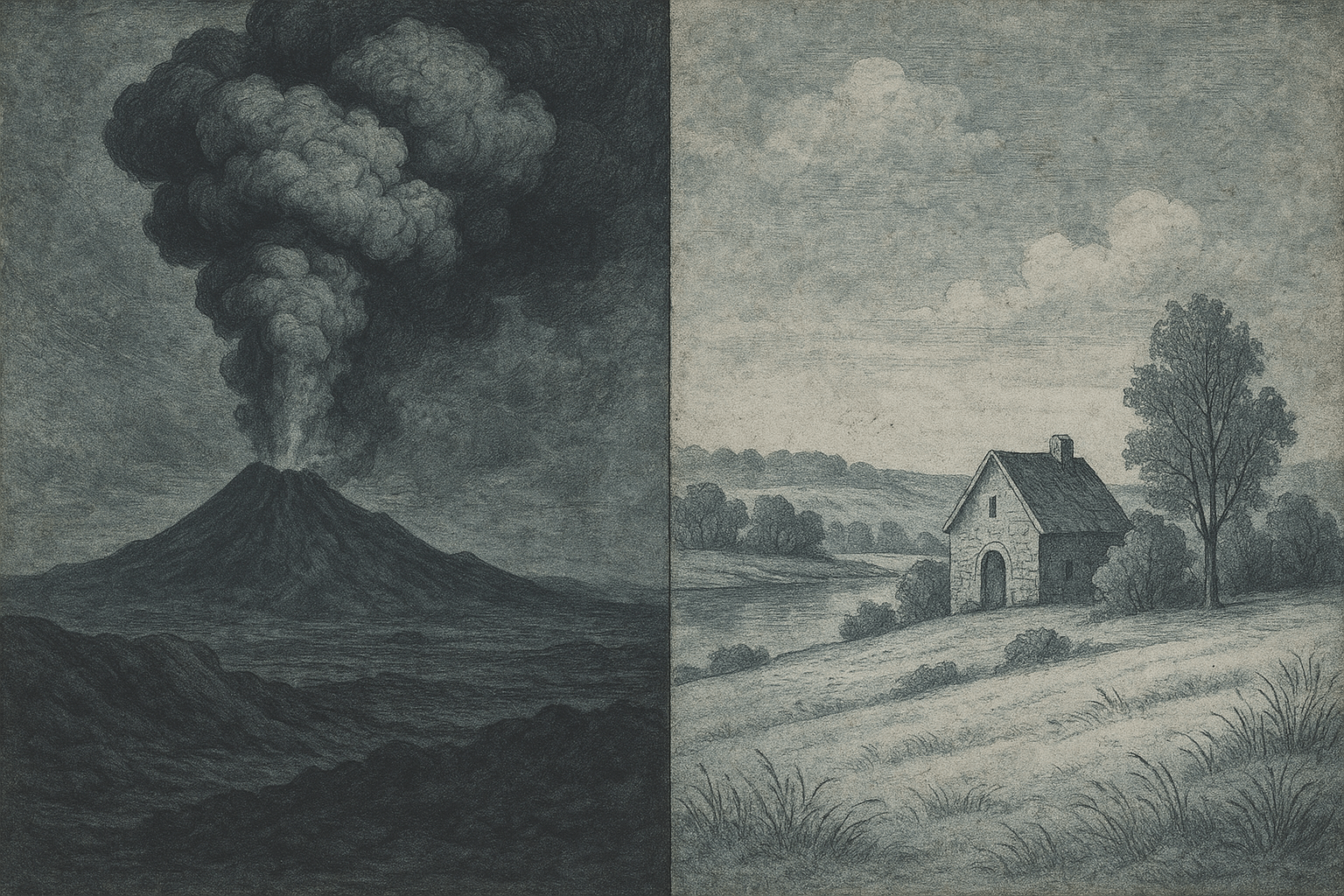

This bizarre and devastating climate anomaly wasn’t an act of divine wrath or a mystical curse. Its origins lay half a world away and a year earlier, in an event of almost unimaginable geological fury: the eruption of a volcano named Tambora.

The Fury of Tambora

In April 1815, on the island of Sumbawa in the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), Mount Tambora roared to life. This wasn’t just any eruption; it was the most powerful volcanic eruption in recorded human history, registering a colossal 7 on the Volcanic Eruptivity Index (VEI). To put that into perspective, it was ten times more powerful than the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa and a hundred times more powerful than Mount St. Helens in 1980.

The immediate effects were cataclysmic. The blast was heard over 1,600 miles away. Pyroclastic flows—superheated torrents of gas, ash, and rock—scoured the island, annihilating villages and killing tens of thousands of people instantly. The collapse of the mountain into its emptied magma chamber triggered tsunamis that ravaged nearby coastlines. But Tambora’s most significant impact was yet to come. The eruption blasted an enormous plume of gas and ash more than 25 miles high, deep into the stratosphere.

A Veil Over the Sun

The crucial component of this plume was an immense quantity of sulfur dioxide. Once in the stratosphere, high above the weather, these gas particles oxidized and mixed with water vapor to form a fine mist of sulfate aerosols. This wasn’t ordinary dust that would fall back to Earth in a few weeks; this was a stable, global veil.

This stratospheric aerosol layer acted like a planetary sunshade, reflecting a critical amount of solar radiation back into space. The result was a drop in the average global temperature by an estimated 0.4–0.7°C (0.7–1.3°F). While that might not sound like much, it was enough to severely disrupt global climate patterns, altering monsoons, shifting storm tracks, and triggering unseasonable killing frosts that would spell disaster for an world that was almost entirely dependent on agriculture.

Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death: Global Chaos

The grim nickname “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death” originated in New England, which was hit particularly hard. The summer of 1816 was a parade of horrors for American farmers:

- May: A late frost killed most of the blossoming fruit trees.

- June: Two major snowstorms blanketed the region, with reports of nearly a foot of snow in parts of Vermont and Quebec. Newly planted crops like corn were wiped out.

- July and August: Lake and river ice were observed as far south as Pennsylvania. Repeated frosts finished off any crops that had managed to survive.

Food prices skyrocketed. The price of oats, a staple for both people and transportation (horses), shot up nearly 800%. Families who had once been self-sufficient were reduced to foraging for roots, berries, and pigeons. The agricultural crisis spurred a massive wave of migration westward from the New England states, as desperate families abandoned their frozen farms in search of more hospitable lands in the Ohio Valley.

Europe fared no better. The continent, already reeling from the Napoleonic Wars, was plunged into famine. Incessant, cold rains caused major rivers like the Rhine to flood their banks. In Ireland, the failed potato, wheat, and oat crops led to a severe famine and a devastating typhus epidemic. In Switzerland, the misery was so profound that people were reportedly eating moss and cats. In Germany, the crisis gave rise to the “Poverty Year”, marked by grain riots and desperate begging.

Even Asia was not spared. The Tambora cloud disrupted the Indian summer monsoon, causing late, torrential rains that contributed to the spread of a new, virulent strain of cholera in Bengal. This strain would eventually spread across the globe, becoming the first great cholera pandemic of the 19th century.

A Summer of Darkness, a Monster’s Birth

Amid the global suffering, the gloomy, wet summer of 1816 had an unexpected cultural consequence. In Switzerland, a group of young, literary-minded English tourists were forced to spend their holiday indoors at the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva. The group included the poets Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Shelley’s 18-year-old future wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, and Byron’s physician, John Polidori.

Frustrated by the “incessant rain” and “an almost perpetual rain”, Byron proposed a challenge: “We will each write a ghost story.” Trapped inside by the volcanic gloom, their imaginations ran wild. Percy Shelley struggled with his story, but the others created legends.

After several nights of discussing galvanism and the reanimation of corpses, Mary had a “waking dream” of a “pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together.” That vision became the basis for her novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, a cornerstone of both Gothic horror and science fiction. At the same time, John Polidori penned The Vampyre, a short story that transformed the folkloric vampire from a brutish peasant ghoul into the suave, aristocratic predator we recognize today, laying the template for Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

The Legacy of a Volcanic Year

The Year Without a Summer was more than just a historical curiosity. It was a stark demonstration of global interconnectedness long before the age of the internet or air travel. Its legacy is woven into science, technology, and art.

The massive crop failures and subsequent shortage of oats for horses is cited as a key motivation for German inventor Karl von Drais to create his “Laufmaschine” or “running machine”—the earliest commercially successful steerable bicycle precursor. On the artistic front, the vast amounts of aerosols in the atmosphere created intensely red and orange sunsets, which are believed to have inspired the dramatic and brilliant skies in the paintings of artist J.M.W. Turner.

Most importantly, the event provides a chilling historical case study of abrupt climate change. It reveals how fragile our agricultural systems are and how a single, distant event can trigger a domino effect of famine, disease, social unrest, and mass migration across the entire planet. The Year Without a Summer stands as a powerful reminder of the immense power of nature and its profound ability to shape the course of human history.