A World Without Restaurants

Imagine a bustling city like Paris in the mid-1700s. You’re hungry, and you’re not at home. What are your options? The world we know, brimming with cafes, bistros, and restaurants for every palate and price point, simply didn’t exist. Your choices were stark and limited.

For travelers, there were inns (auberges). Here, you paid for a room and a meal, but you had no say in what that meal was. You ate at a communal table, the table d’hôte (“the host’s table”), and were served whatever the innkeeper had prepared for that day. It was functional, but hardly a culinary experience. For locals, there were taverns that served wine and rudimentary dishes, but these were often rowdy, male-dominated spaces. You could also buy prepared foods from caterers, or traiteurs, who would cook large quantities of food for events, but you couldn’t just walk in and order a single portion for dinner.

This rigid system was enforced by a powerful network of guilds. Each guild held a strict monopoly over a specific food category. The rôtisseurs could sell you roasted meats, the pâtissiers could sell you pies, and the vinaigriers could sell you sauces. A butcher couldn’t cook and sell a stew, and a baker couldn’t sell a meat pie. This structure stifled creativity and, most importantly, consumer choice.

A “Restorative” Revolution

The first crack in this monolithic system appeared around 1765. The change didn’t come from a master chef or a wealthy aristocrat, but from a Parisian shopkeeper who is known to history simply as Monsieur Boulanger. His shop, on the rue des Poulies near the Louvre, wasn’t a grand dining hall. It was a modest establishment that specialized in one thing: soups.

Boulanger called his rich, slow-simmered broths restaurants, a French word meaning “restoratives.” They were marketed as health food, intended to restore the energy of those with delicate appetites and weak constitutions. Above his door, he placed a sign with a clever, slightly cheeky biblical pun in Latin:

Venite ad me omnes qui stomacho laboratis et ego vos restaurabo.

This translates to, “Come to me, all who labor in the stomach, and I will restore you.”

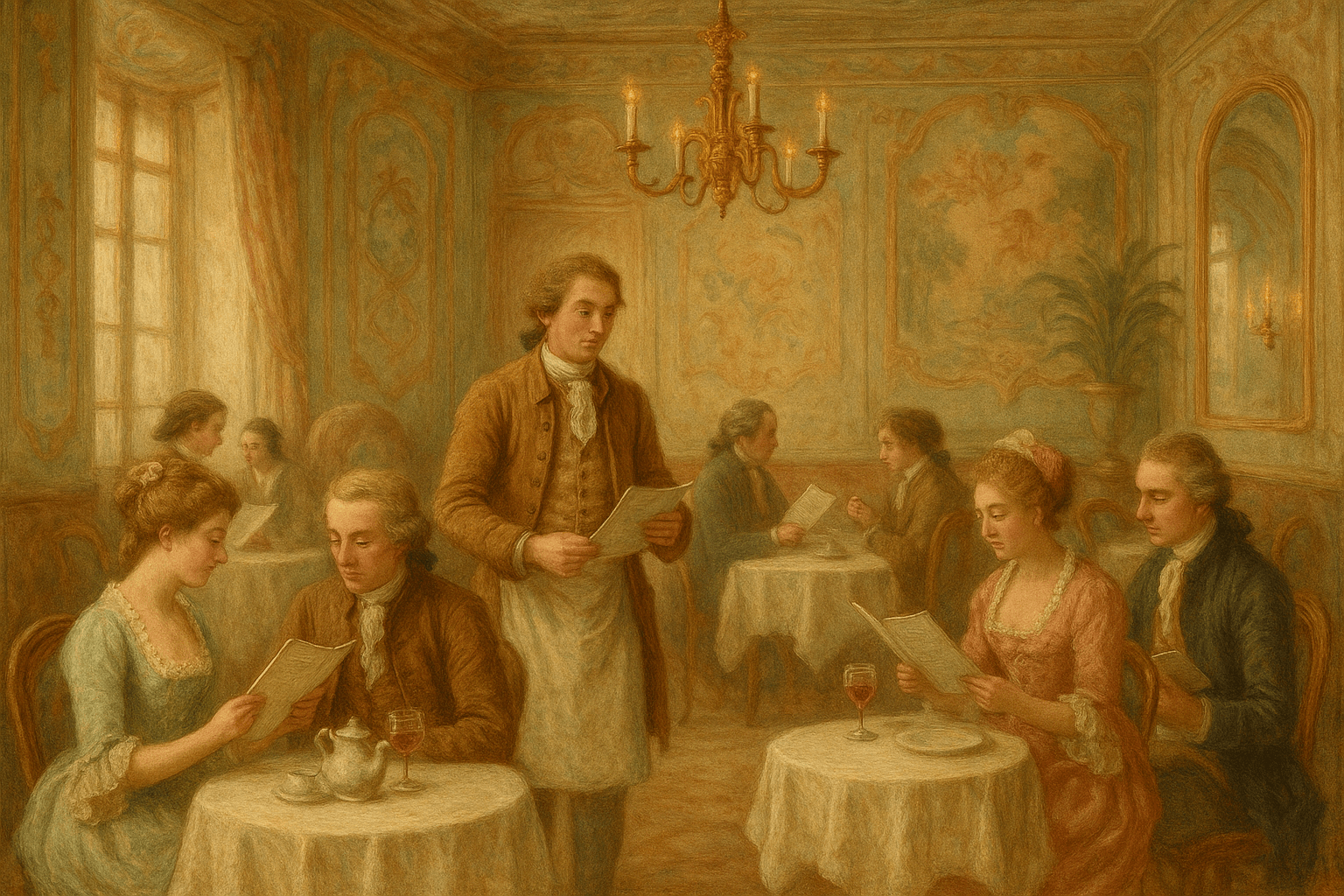

This alone was innovative. But Boulanger’s true genius lay in three breaks from tradition. First, he offered a choice of several different “restorative” broths. Second, he served them at small, individual marble tables, offering privacy and a personal experience. Third, his business model was based on serving individuals whenever they were hungry during opening hours, not a single meal at a fixed time. These elements—a written menu, private tables, and flexible service—were the foundational DNA of the modern restaurant.

The Trial of the Sheep’s Feet

Emboldened by his success, Boulanger decided to expand his menu. He added a new, more substantial dish: sheep’s feet simmered in a creamy white sauce (pieds de mouton à la poulette). To us, it sounds like a simple menu addition. To the Parisian culinary world of 1765, it was a declaration of war.

The powerful caterers’ guild, the traiteurs, immediately saw this as an existential threat. They held the exclusive right to sell ragoûts, or stews with meat. They argued that Boulanger’s sheep’s feet dish was, in essence, a ragoût, and therefore he was illegally infringing on their monopoly. They sued him.

The case went all the way to the Parisian Parlement, the highest court in the land. The future of dining hung in the balance. Boulanger’s lawyers mounted a clever defense. They argued with gastronomic pedantry that the sheep’s feet, served in their sauce, did not technically constitute a ragoût. The case became a sensation, with all of Paris debating the precise culinary definition of a stew. In a landmark decision, the court sided with Boulanger. The sheep’s feet were not a ragoût. He was free to sell them.

This legal victory was monumental. It created a loophole in the guild system, proving that the ancient monopolies could be challenged and defeated. Other entrepreneurs followed Boulanger’s lead, opening their own “restorative” houses and cautiously expanding their menus.

The Revolution on a Plate

While Boulanger lit the spark, it was the French Revolution in 1789 that fanned it into an inferno. Before the Revolution, the greatest chefs in France were not public figures. They were the private employees of the great aristocratic houses, a symbol of the nobility’s power and opulence. A duke or prince’s status was measured, in part, by the quality of his table and the genius of his chef.

Then came the Terror. Aristocrats fled France, were imprisoned, or met their fate at the guillotine. Their vast households were dismantled, and suddenly, hundreds of France’s most talented, classically trained chefs were out of a job. At the same time, in 1791, the revolutionary government officially abolished the trade guilds, removing all legal barriers to culinary enterprise.

With their patrons gone and their skills in high demand, these unemployed chefs did the only thing they could: they opened establishments to serve the public. A new class of customer was emerging—the wealthy bourgeoisie—who had the money and the desire to experience the luxury that was once the exclusive domain of the nobility. For the first time, a person could, by simply paying the bill, eat food prepared by the former chef of a prince.

One of the earliest and most famous examples was the Grande Taverne de Londres, opened in 1782 by Antoine Beauvilliers, former chef to the future King Louis XVIII. He is often called the true founder of the fine dining restaurant, combining four key elements: an elegant dining room, knowledgeable waiters, a well-stocked wine cellar, and, of course, exquisite cooking. Beauvilliers set the standard, and after 1789, dozens more followed. By 1804, Paris had over 500 restaurants, transforming the city into the culinary capital of the world.

The Legacy of a Parisian Innovation

From a humble Parisian soup-seller to the unintended consequences of a political revolution, the birth of the restaurant was a story of defiance, innovation, and social upheaval. It democratized luxury, turning the private art of aristocratic cooking into a public experience. The core concepts established in late 18th-century Paris—the menu, the private table, the individual choice, the concept of dining as entertainment—spread across the globe.

So the next time you sit down at a restaurant, peruse a menu, and order precisely what you want, take a moment to think of Monsieur Boulanger and his restorative broth. You are taking part in a revolutionary act, one that began over 250 years ago with a bowl of soup and a side of stubbornness.