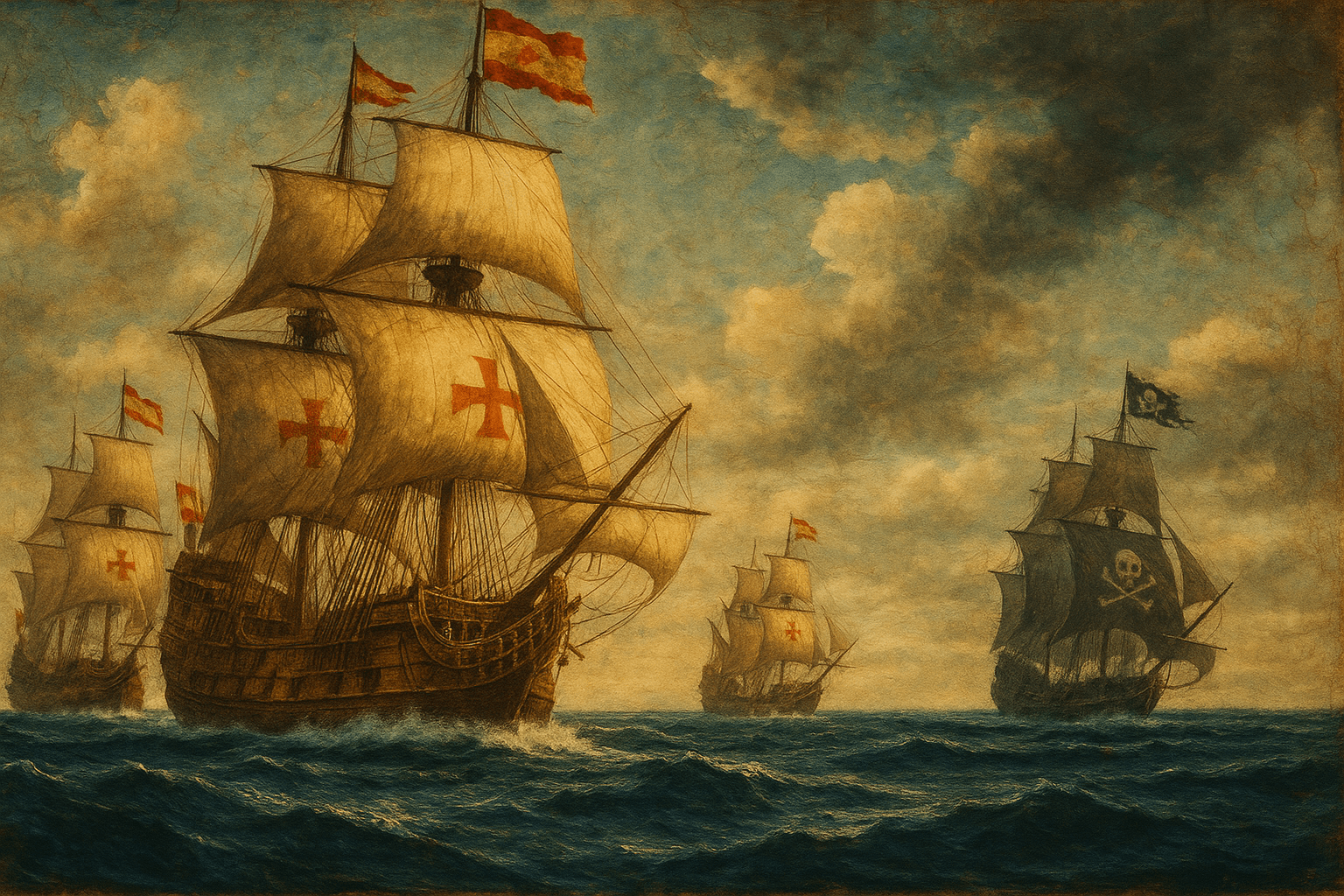

For over two centuries, the waves of the Atlantic Ocean witnessed a spectacle of unprecedented scale and wealth: the Spanish Treasure Fleets. Known as the Flota de Indias, this legendary convoy system was the lifeline of the Spanish Empire, a seaborne pipeline that funneled the riches of the New World into the coffers of the Old. It was a marvel of logistics that funded European wars, fueled a golden age of art and culture, and forever changed the global economy—all while braving the twin threats of bloodthirsty pirates and the ocean’s untamable fury.

A River of Silver from a Mountain of Death

The story of the treasure fleets begins not on the sea, but deep within the earth of the Americas. In 1545, Spanish conquistadors discovered a literal mountain of silver in a remote, high-altitude location in modern-day Bolivia. They called it Potosí. The riches were so immense that the phrase “vale un Potosí” (“it’s worth a Potosí”) became a common Spanish expression for something of incalculable value. Soon after, another major silver vein was struck in Zacatecas, Mexico.

This newfound wealth came at a horrific human cost. The Spanish crown implemented the mita system, a brutal form of forced labor inherited from the Incas, compelling tens of thousands of indigenous people to toil in the treacherous mines. Conditions were deplorable, with workers facing cave-ins, mercury poisoning from the refining process, and sheer exhaustion. Potosí was not just a mountain of silver; it was a mountain that consumed human lives by the thousands, a dark foundation upon which the Spanish Empire was built.

Once extracted, the raw silver was transported by llama and mule train to mints, where it was smelted into ingots or stamped into the most famous coin in history: the silver peso de ocho, or “piece of eight.” This was the currency that would fill the holds of the treasure galleons.

The Convoy System: A Fortress on the Water

Moving such incredible wealth across an ocean infested with rivals was a monumental challenge. A single ship, no matter how well-armed, was a tempting target for French corsairs, English privateers, and pirates of every nation. Spain’s solution was ingenious and audacious: a convoy system on an imperial scale.

The system consisted of two primary fleets that departed from Seville (and later Cádiz) each year:

- The Flota de Nueva España (New Spain Fleet): This fleet sailed to Veracruz in modern-day Mexico. It collected the silver from the Mexican mines, as well as exotic goods like Chinese silk and porcelain that had traveled across the Pacific on the Manila Galleons to Acapulco and were then hauled overland.

- The Galeones de Tierra Firme (Mainland Galleons): This fleet sailed to the “Spanish Main”, primarily to Cartagena (in Colombia) and Portobelo (in Panama). Portobelo held a massive trade fair upon the fleet’s arrival, where the silver from Potosí—which had been painstakingly carried by mule train across the Isthmus of Panama—was exchanged for European goods.

After conducting their business and overwintering in the Americas, the two fleets would rendezvous in the heavily fortified port of Havana, Cuba. Here, ships were repaired, re-provisioned, and organized for the final, most dangerous leg of the journey: the transatlantic crossing back to Spain. The combined fleet was a formidable sight, often comprising 50 to 100 ships, including merchant vessels (naos) and heavily armed escort galleons bristling with cannons and soldiers.

Pirates, Privateers, and Hurricanes

The image of a pirate ship bearing down on a lumbering Spanish galleon is etched into our popular imagination. While attacks certainly happened, the success of the convoy system lay in its strength in numbers. For over 200 years, an entire fleet was captured by enemies only once.

The exception was a stunning blow to Spanish pride and finance. In 1628, the Dutch privateer Piet Hein, working for the Dutch West India Company, managed to trap and seize the entire New Spain fleet in Matanzas Bay, Cuba, without a major battle. The Dutch captured a staggering amount of silver, gold, and merchandise, a heist that funded the Dutch army for eight months and nearly bankrupted the Spanish crown.

More common were attacks on stragglers—ships that had become separated from the fleet due to storms or damage. Figures like England’s Sir Francis Drake, celebrated as a hero at home but despised as a pirate (El Draque) by Spain, grew rich by raiding Spanish ports and picking off lone treasure ships.

However, the greatest threat to the Flota de Indias was not man, but nature. Hurricanes in the Caribbean and violent storms in the Atlantic were far more destructive than any pirate fleet. The schedule of the fleets was built around avoiding the worst of the hurricane season, but delays were common. A miscalculation could be catastrophic.

- In 1622, a fleet sailing from Havana was struck by a powerful hurricane. Eight ships were lost, including the legendary Nuestra Señora de Atocha. It sank with a treasure so vast that when it was finally discovered by Mel Fisher in 1985, it yielded over $400 million in silver, gold, and emeralds.

- In 1715, another hurricane obliterated the returning treasure fleet off the coast of Florida, sinking 11 of its 12 ships. The disaster scattered treasure along Florida’s coastline, giving rise to its name, the “Treasure Coast.”

The End of an Era

By the mid-18th century, the magnificent treasure fleet system had begun to decline. Silver production in the Americas was slowing, and constant European wars had weakened Spain’s naval dominance. The Bourbon Reforms liberalized trade, allowing for more frequent, individual sailings under a registration system (navíos de registro), which proved more flexible and efficient than the slow, rigid convoy.

The last official treasure fleet sailed in 1776, bringing an end to the era. The great river of silver had dwindled to a stream, and the fortress on the water was no longer necessary.

The legacy of the Spanish Treasure Fleets is complex. They were the engine of a global empire and a catalyst for economic change, but they were also built on exploitation and slavery. They leave behind a dual history: one of imperial grandeur, global finance, and logistical genius; the other of sunken treasure, romantic pirate tales, and the profound human suffering that made it all possible.