Imagine a world without borders, a vast, rolling sea of grass stretching for thousands of miles. Across this landscape thunders a nation on horseback, their arrows whistling through the air, their warriors adorned in intricate gold. These are the Scythians, the legendary nomadic masters of the Eurasian steppe, a people who left no cities or written histories, but whose legacy is etched in the treasures they buried and the terror they instilled in the hearts of empires.

Who Were the Scythians?

Appearing in the historical record around the 8th century BCE, the Scythians were not a single, unified empire but a sprawling confederation of related, Iranian-speaking tribes. Their domain was the Pontic-Caspian steppe, a massive territory that today covers parts of Ukraine, southern Russia, and Kazakhstan. For nearly five centuries, they were the dominant power in this vast region.

Their lifestyle was entirely shaped by the steppe. As pastoral nomads, they lived in felt-covered wagons that served as mobile homes, following their vast herds of horses, cattle, and sheep in a constant search for fresh pasture. To the settled civilizations on their borders, they were the ultimate “barbarians”—enigmatic, wild, and dangerously unpredictable. But to see them as mere wanderers is to miss the point; their movements were a calculated, seasonal rhythm, a deep understanding of the land that was their greatest strength.

Masters of the Horse and Bow

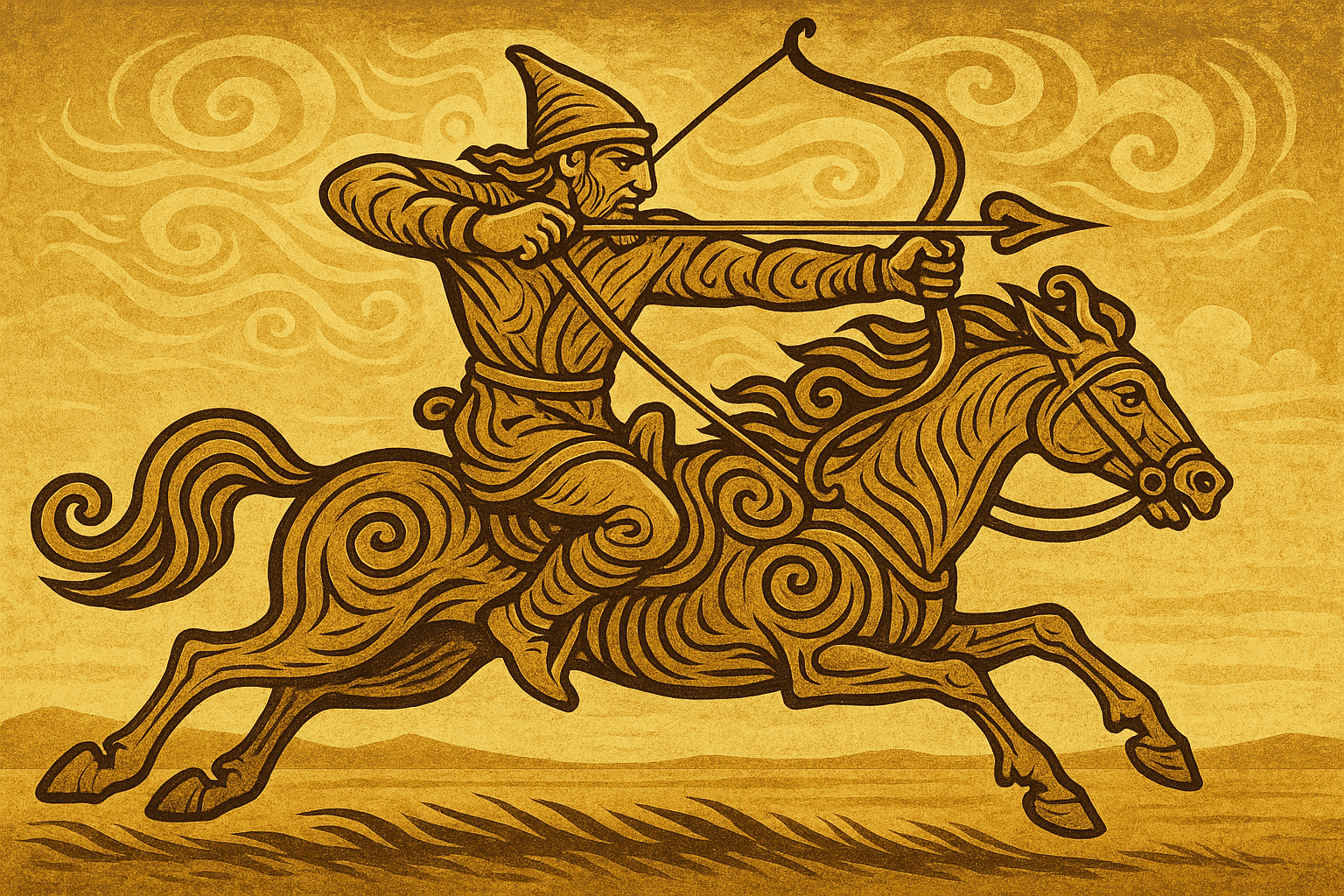

The Scythian and their horse were one. They were among the world’s first and greatest horsemen, spending so much of their lives in the saddle that skeletal remains often show bowed legs. Their military genius was built upon this unparalleled equestrian skill, combined with a revolutionary weapon: the Scythian composite bow.

Crafted from layers of wood, sinew, and horn, this bow was relatively small—perfect for wielding on horseback—but possessed incredible power and range. A Scythian warrior could rain down a barrage of bronze-tipped arrows on an enemy, wheel their horse around, and gallop out of reach before a counter-attack could even be organized. Their most famous and feared tactic was the feigned retreat. A Scythian host would pretend to break and flee, luring their overconfident enemy into a chaotic pursuit. Then, in a stunning display of horsemanship, the warriors would twist in their saddles and fire a deadly volley of arrows backward into the disorganized ranks. This maneuver, often called the “Parthian Shot” after a later steppe people, made the Scythians nearly invincible on open ground.

A Culture Forged in Gold and Tattoos

While their lifestyle was mobile, Scythian culture was incredibly rich and sophisticated. They were masters of metalwork, producing breathtaking objects in what is known as the “animal style.” Their art is a dynamic, swirling world of real and mythical creatures: stags with elaborate antlers, coiled panthers, ferocious griffins, and birds of prey. These motifs adorned everything from weapons and horse harnesses to clothing plaques and jewelry.

The material of choice was gold. Scythian chieftains and the warrior elite displayed their wealth and status with solid gold torcs, bracelets, and ceremonial weapons. One of the most famous examples is the magnificent golden pectoral (a chest ornament) from the Tovsta Mohyla burial mound in Ukraine. This solid gold masterpiece, weighing over a kilogram, depicts dramatic scenes of griffins attacking horses on its upper register, and surprisingly peaceful, detailed scenes of Scythian daily life—milking a ewe, mending a garment—on its lower register.

Even their bodies were canvases. Discoveries of frozen Scythian mummies in the Altai Mountains, such as the famous “Siberian Ice Maiden”, have revealed that both men and women bore elaborate, dark-blue tattoos. These intricate designs mirrored the animal art seen in their goldwork, marking them as members of their tribe in both life and death.

Encounters with Empires: Greeks and Persians

The Scythians were not isolated. On the northern shores of the Black Sea, they encountered Greek colonists from city-states like Olbia. A complex relationship of trade and conflict emerged. The Scythians traded grain, furs, and slaves for Greek wine, fine pottery, and luxury goods. Much of the spectacular goldwork found in Scythian tombs was likely crafted by Greek artisans working to satisfy the specific tastes of their wealthy nomadic clients.

It is from the Greek historian Herodotus, the “Father of History”, that we get our most vivid, if sometimes sensationalized, descriptions of Scythian life. He wrote of their fierce loyalty, their practice of drinking from the skulls of their enemies, and their grimly elaborate funeral rituals.

Perhaps the most telling encounter was with the mighty Persian Empire. Around 513 BCE, King Darius the Great led a massive army onto the steppe to punish the Scythians for their cross-border raids. The Scythians, however, refused to meet the Persians in a decisive battle. Led by their king, Idanthyrsus, they simply retreated deeper and deeper into the endless grasslands, poisoning wells and burning pastures as they went. They harassed the long Persian supply lines with lightning-fast raids, draining the strength of the invading army. Frustrated, Darius sent a message demanding to know why they wouldn’t stand and fight. Idanthyrsus’s reply, as recorded by Herodotus, perfectly captures the nomadic spirit: “We have no cities or cultivated land to worry about… But we do have the tombs of our fathers. Find them, try to destroy them, and you will learn whether we will fight you or not.” Unable to pin them down and with his army starving, Darius was forced into a humiliating retreat.

The Royal Tombs: Kurgans

Since they left no written records, our gateway into the Scythian world is through their tombs. The elite were buried in massive earthen mounds called kurgans, some of which still dot the Eurasian steppe today. These were not simple graves but elaborate burial chambers designed as subterranean houses for the afterlife.

A deceased chieftain was laid to rest with their most prized possessions: weapons, clothing, and a staggering amount of gold. But the rituals, as described by Herodotus and confirmed by archaeology, were grim. To serve their master in the next world, a retinue of servants, concubines, and horses were sacrificed and buried alongside him. The scale of these horse sacrifices could be immense, with some kurgans containing the remains of hundreds of animals, all interred with their elaborate harnesses and saddles. These tombs are time capsules, providing priceless insights into a culture’s beliefs, art, and daily life.

Legacy of the Steppe Warriors

By the 2nd century BCE, the Scythians were gradually displaced and absorbed by another nomadic group, the Sarmatians. Yet, their legacy endured. Their revolutionary style of mobile, cavalry-based warfare would influence armies for over a millennium. Their stunning animal-style art left its mark on cultures from Persia to China. And they sparked the Greek imagination, with some scholars believing that tales of Scythian warrior women, backed by archaeological finds of female graves containing weapons, provided the basis for the myth of the Amazons.

The Scythians were more than just the “barbarians” their settled neighbors saw. They were a dynamic and complex people who mastered their environment and created a unique and enduring culture. They remind us that history is not only written in stone and parchment, but also in gold, on skin, and across the silent, endless plains of the steppe.