Their story is a tantalizing glimpse into a forgotten era of globalization, a testament to human ingenuity and connection in a world we often imagine as dark and disconnected. But who were these master traders, how did they operate, and why did they vanish from the pages of history?

Who Were the Radhanites?

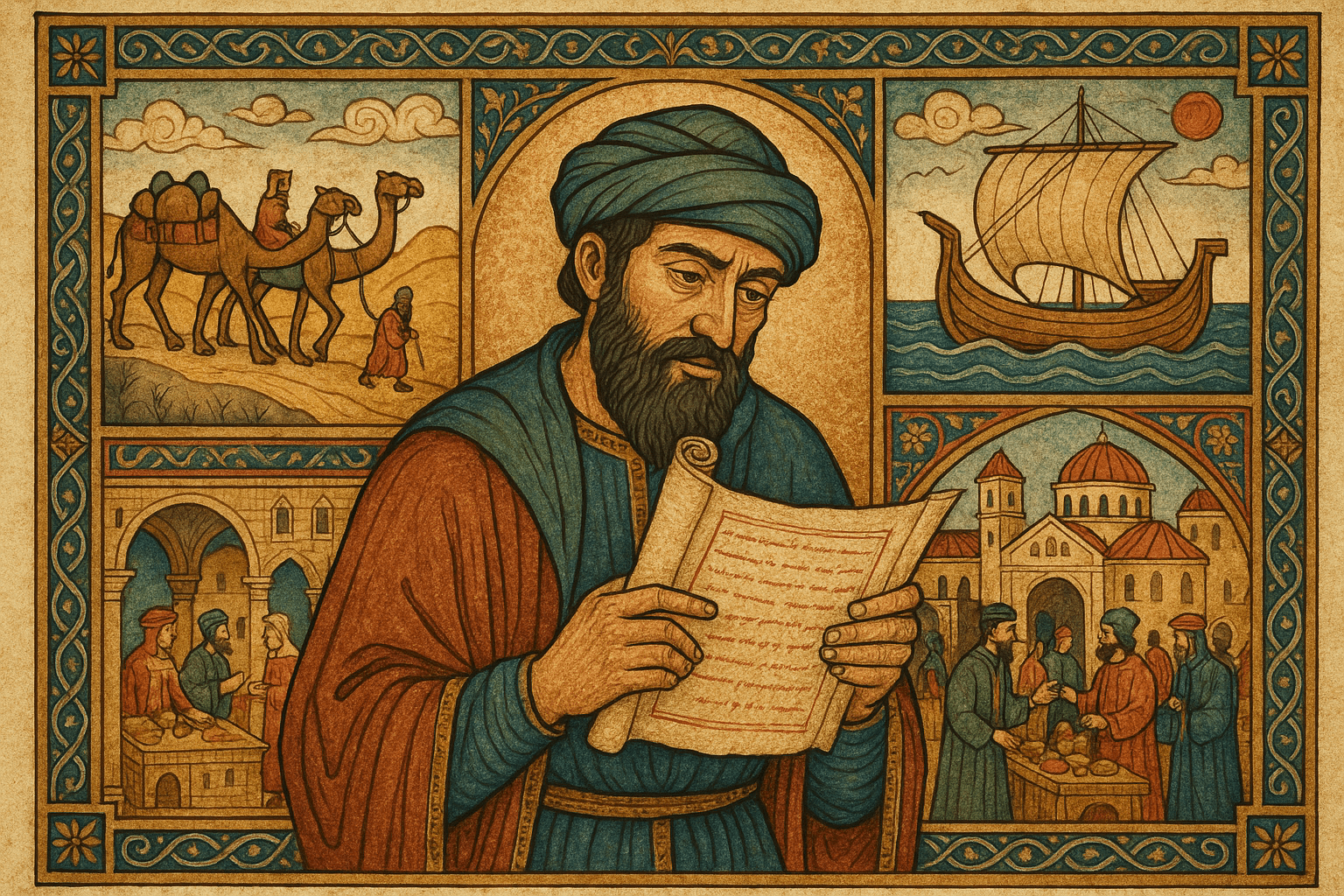

Almost everything we know about this mercantile group comes from a single, remarkable source: the 9th-century Persian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh and his work, The Book of Roads and Kingdoms. Writing around 870 AD from Baghdad, the heart of the Abbasid Caliphate, he described the “routes of the Jewish merchants called Radhanites.”

The very name “Radhanite” is a mystery. Scholars have proposed several theories:

- It may derive from the Persian phrase “rah dan”, meaning “one who knows the way.”

- It could refer to the Radhan district in ancient Mesopotamia, a potential origin point for the group.

- Another theory links them to the Rhône River Valley in France, a major launching point for their trade routes.

Whatever their name’s origin, Ibn Khordadbeh is clear about their identity: they were Jewish merchants. This was not incidental; it was central to their success. In an age when the world was sharply divided between Christendom and the Islamic Caliphates, the Jewish diaspora provided a unique advantage. A Radhanite merchant from Lyon could find a welcoming community, a shared language (Hebrew), a common legal framework, and a network of trust in distant cities like Baghdad or Cairo. They were the perfect middlemen, belonging everywhere and nowhere at once.

Masters of the Globe: The Four Great Routes

Ibn Khordadbeh outlines four main routes the Radhanites used, each an epic undertaking that showcases their incredible ambition and logistical prowess. These were not simple trips but multi-year odysseys that crossed hostile territories, treacherous seas, and vast deserts.

1. The Southern Sea Route: Merchants traveled from France by sea to Egypt, where they transferred their goods from ship to camel. They trekked overland to the Red Sea port of al-Qulzum (near modern Suez), then sailed to Jeddah (the port for Mecca) before continuing to India and China.

2. The Broken Land Route: This route also started in France but went overland through Europe and Syria. From there, merchants crossed into modern-day Iraq, sailed down the Tigris River to the Persian Gulf, and then embarked for India and China. It was a complex path that required “going back and forth” between sea and land.

3. The Khazar Land Route: Perhaps the most fascinating route, this path took the Radhanites east from France across Europe. They crossed the lands of the Slavs to Itil, the capital of the Khazar Khaganate—a massive Turkic empire whose elite had converted to Judaism. This provided a crucial, friendly hub. From Itil, they crossed the Caspian Sea, journeying through Central Asia along the Silk Road until they reached China.

4. The Iberian Route: A fourth, more localized route involved crossing the sea from Spain or France directly to North Africa (the Maghrib) and then continuing east to the Levant.

These journeys required incredible linguistic skill. Ibn Khordadbeh notes that the Radhanites spoke “Arabic, Persian, Roman (Greek and Latin), the language of the Franks, the Spanish, and the Slavs.” They were the ultimate polyglots, chameleons who could negotiate a deal in a Frankish court one year and a Persian bazaar the next.

The Cargo of Continents

The Radhanites weren’t just moving everyday goods; they were the purveyors of luxury, status, and power. Their cargo represented the most coveted items of the medieval world.

From the West to the East, they carried:

- Slaves: Ibn Khordadbeh specifically mentions eunuchs, female slaves, and boys, a dark but hugely profitable trade that supplied the courts and harems of the Abbasid Caliphate. Many of these slaves were of Slavic origin (the root of the word “slave”).

- Weapons: High-quality Frankish swords were especially prized in the East.

- Furs: Pelts from beavers, martens, and other European animals were highly sought-after luxuries.

- Textiles: Rich brocades found a ready market in the wealthy cities of the Islamic world.

From the East to the West, they brought back the exotic and the aromatic:

- Spices: Musk, aloe, camphor, cinnamon, and cloves were worth more than their weight in gold in Europe, used for medicine, perfume, and flavoring the food of the elite.

- Silk: This legendary fabric was a symbol of ultimate wealth and power in European courts and churches.

The Vanishing Act: Where Did the Radhanites Go?

For roughly a century, the Radhanites appear to have dominated this global trade. And then, after the late 10th century, they disappear from the historical record. The name “Radhanite” is no longer mentioned. What happened?

There is no single answer, but a combination of factors likely led to their decline:

1. The Rise of Italian City-States: Merchants from Venice, Genoa, and Pisa began to build their own powerful maritime networks in the Mediterranean. They were aggressive competitors who eventually muscled out the Radhanites on the crucial sea routes.

2. Political Collapse: Two key pillars of the Radhanite network crumbled. The fall of the Tang Dynasty in China in 907 led to chaos along the eastern Silk Road. More importantly, the collapse of the Khazar Khaganate in the late 10th century destroyed the safe haven and critical hub for their northern land route.

3. The Crusades: Beginning in 1096, the Crusades created a new era of intense and violent conflict between the Christian and Islamic worlds. The relatively open borders that the Radhanites had expertly navigated began to slam shut. Their position as neutral intermediaries became untenable in a world of holy war.

4. Assimilation and Evolution: It’s also likely the Radhanites didn’t just vanish but evolved. Their trade networks may have been absorbed by other emerging Jewish merchant communities, like the Maghribi traders of North Africa, whose activities are well-documented in the Cairo Geniza texts. They may have fragmented, trading on more localized routes rather than spanning continents.

The Radhanites are a powerful reminder that history is often shaped not by the clash of empires, but by the quiet, persistent threads of connection woven between them. For a brief, brilliant period, these Jewish merchants were the world’s weavers, connecting cultures and economies in a way that would not be seen again for centuries. Their story, pieced together from a few precious paragraphs, challenges us to look for the hidden networks that underpin our own globalized world.