From Syriac Roots to a Distinct Identity

The origins of the Maronites trace back to the late 4th and early 5th centuries AD in the region of Syria Secunda, near modern-day Aleppo. Their spiritual father was a Syriac-speaking hermit named Saint Maron (d. 410 AD). Maron was not a preacher or a theologian but an ascetic who chose a life of extreme piety and prayer in the open air. His devotion attracted a large following of disciples who sought to emulate his way of life, forming the nucleus of the Maronite movement.

The critical turning point that forged their distinct identity came with the great theological debates of the 5th century. After the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, the Christian world was fiercely divided over the nature of Christ. The Council’s declaration that Christ had two natures—one divine and one human—in one person was rejected by many Eastern Christians, who became known as Monophysites (believing in a single, divine nature).

The followers of Saint Maron, however, were staunch defenders of the Chalcedonian position. This theological stance put them at odds with the dominant Jacobite (Syriac Orthodox) and Byzantine authorities in the region. Facing persecution for their beliefs, the Maronite community began a gradual but pivotal migration from the plains of Syria towards a new sanctuary: the formidable and protective peaks of Mount Lebanon.

A Fortress in the Mountains

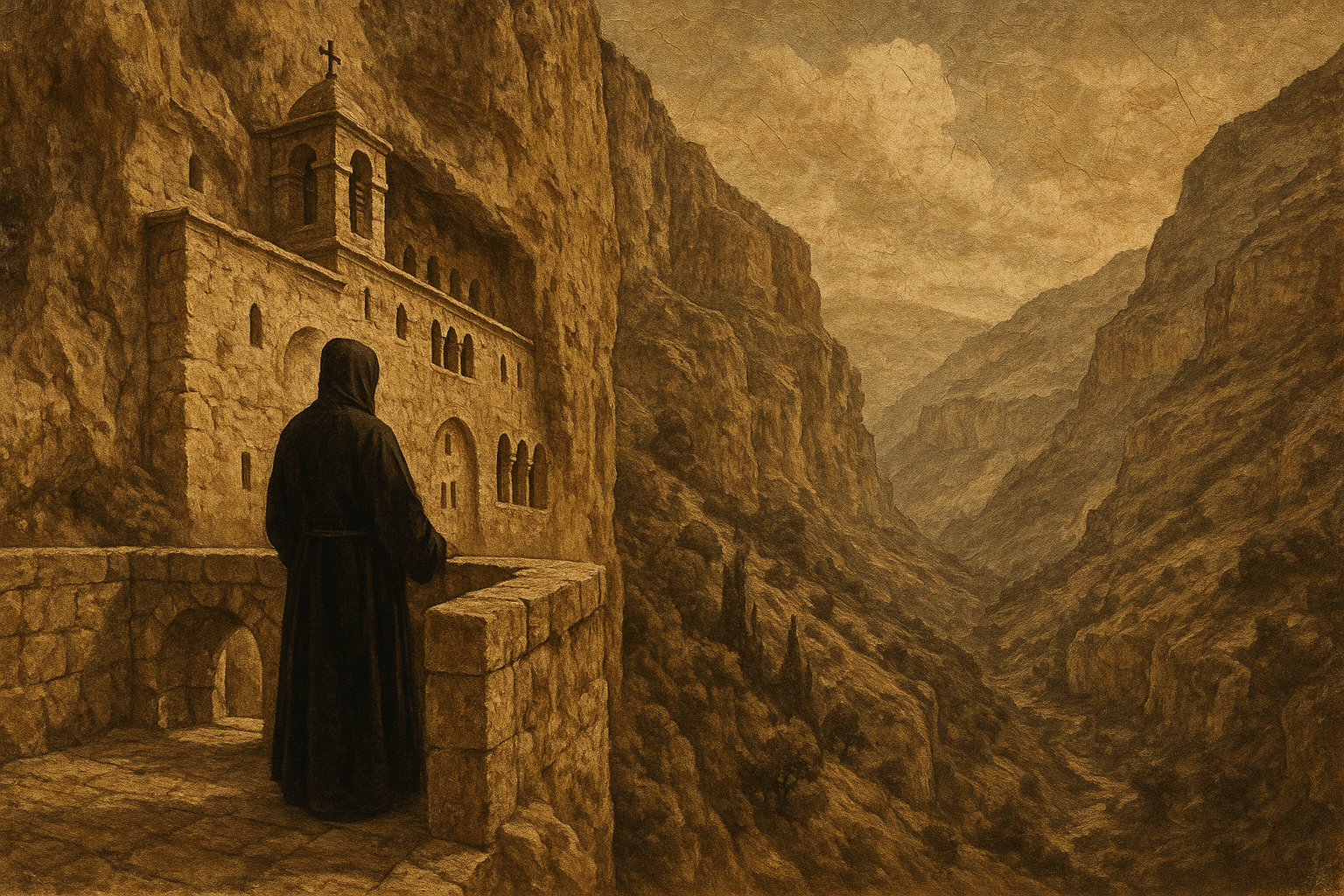

The migration to Mount Lebanon, which intensified following the Arab conquests of the 7th century, was the defining event in early Maronite history. The remote valleys and inaccessible peaks of the northern Lebanese mountains, particularly the sacred Kadisha Valley (a UNESCO World Heritage site), became their fortress and homeland. Here, shielded from the political and religious turmoil of the lowlands, the Maronites preserved their unique faith, culture, and Aramaic-Syriac language.

It was in this mountain refuge that they solidified their ecclesiastical structure. Around the year 685 AD, they elected their first patriarch, Saint John Maron, asserting their administrative independence and establishing the Maronite Patriarchate of Antioch. Monasteries, such as the famous Monastery of Qozhaya, became vital centers of spirituality, learning, and agricultural innovation, anchoring Maronite life in their new territory. For centuries, these mountain communities lived in relative isolation, developing a fierce spirit of independence and a deep connection to the land that had given them shelter.

An Alliance with the West: The Crusaders

This long isolation was dramatically interrupted at the end of the 11th century with the arrival of the First Crusade. As the European knights marched through the Levant, they were astonished to find a thriving, organized Christian community in the mountains. The Maronites, for their part, saw the Catholic Franks not as invaders, but as co-religionists.

A natural alliance was forged. The Maronites provided the Crusaders with invaluable local knowledge, acting as guides and fierce allies in their campaigns. This encounter re-established a direct and enduring link between the Maronites and the Latin West. In 1182, the Maronites formally reaffirmed their communion with the Pope in Rome. It is crucial to note that from a Maronite perspective, this was not a “conversion” but a reaffirmation of a bond they believe was never broken. This act solidified their status as an Eastern Catholic Church—one that maintains its own Syriac liturgy, theology, and governance while being in full communion with the Holy See.

This relationship with Europe, particularly with the Kingdom of France, would profoundly shape their destiny for centuries to come.

The Ottoman Era and the Road to a Nation

Under the subsequent Mamluk and Ottoman Empires, the Maronites, like other non-Muslims, were organized into a millet—a protected, self-governing religious community. While they faced periods of hardship and persecution, their connection to Europe provided a degree of security. France, styling itself as the “Protector of the Eastern Christians”, frequently intervened on their behalf.

The 19th century was a period of both trauma and transformation. An 1860 civil conflict between the Maronites and their Druze neighbors resulted in widespread massacres and devastation. The horrific violence prompted a swift European military intervention, led by France. The result was the creation of the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate in 1861. This autonomous province within the Ottoman Empire was governed by a non-Lebanese Ottoman Christian and administered by a council representing the various religious communities. It was, in essence, the proto-state of Lebanon, with the Maronites at its political and demographic core.

Shaping a Nation: The Maronite Role in Modern Lebanon

The final collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I presented a historic opportunity. As the French and British carved up the Middle East, Maronite leaders, championed by Patriarch Elias Peter Hoayek, lobbied tirelessly for the creation of an independent, expanded Lebanese state. They argued for a “Greater Lebanon” that would include not just their mountain heartland but also the coastal cities of Beirut, Tripoli, and Sidon, as well as the fertile Bekaa Valley and southern Lebanon. Their vision was for a pluralistic nation that could serve as a refuge for all of the region’s minorities, anchored by a strong Christian presence.

In 1920, the French declared the State of Greater Lebanon, largely along the lines the Maronites had advocated. This set the stage for the country’s independence. Upon full independence in 1943, Lebanon’s political leaders agreed to the National Pact, an unwritten agreement that established the framework for a multi-confessional state. This power-sharing system institutionalized the Maronites’ preeminent role by stipulating that:

- The President must be a Maronite Christian.

- The Prime Minister must be a Sunni Muslim.

- The Speaker of Parliament must be a Shia Muslim.

The Maronites had succeeded in moving from a community of mountain refugees to the primary architects and guarantors of the modern Lebanese state.

A Legacy of Resilience

The story of the Maronites is a powerful testament to the endurance of identity through centuries of upheaval. They are a people whose faith was forged in theological controversy, whose culture was preserved in mountain strongholds, and whose political destiny became intertwined with both Europe and the creation of Lebanon. While modern Lebanon faces immense challenges that test its foundational pact, the 1,500-year history of the Maronites remains a central and indelible part of this complex and captivating nation’s past, present, and future.