The Hermit on the Mountain: Origins with Saint Maron

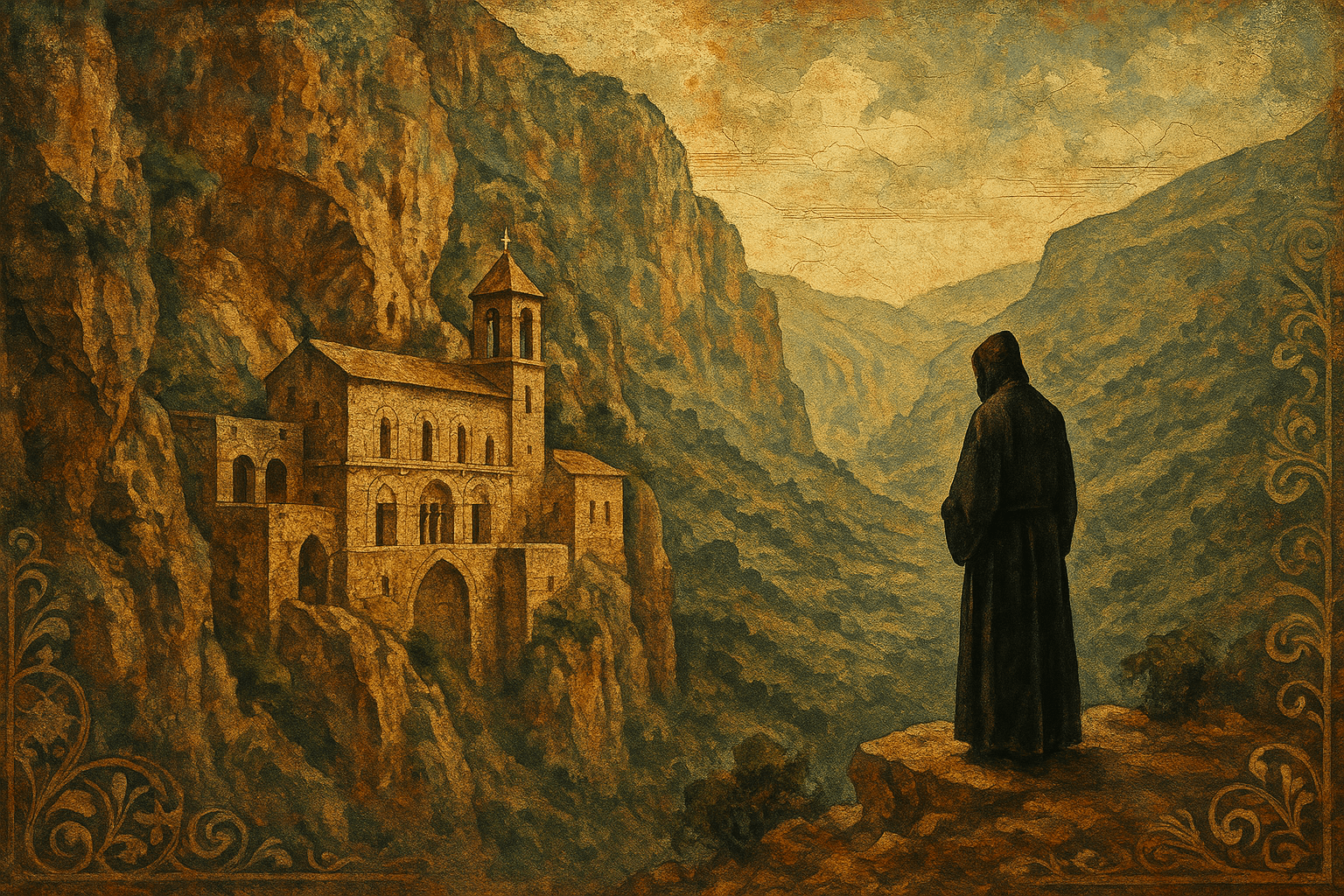

The Maronite story begins not with a council or a king, but with a single man of profound faith. In the 4th century AD, a Syriac-speaking monk named Maron (or Maroun) retreated from the world to embrace a life of asceticism in the open air on a mountain near Antioch, in what is now modern-day Syria. He lived a life of prayer, fasting, and exposure to the elements, devoting himself entirely to God. His reputation for holiness and his purported gift of healing attracted a large following of disciples.

These early followers were not just admirers; they formed a vibrant monastic movement. After Maron’s death around 410 AD, his disciples built a monastery in his honor, Beth Maroun, which became the nucleus of the nascent Maronite Church. Crucially, they inherited his language and liturgical traditions. They prayed and worshipped in Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic—the very language spoken by Jesus Christ and his Apostles. This Syriac heritage remains a cornerstone of Maronite identity, connecting them directly to the earliest days of Christianity in the Levant.

A Fortress of Faith: The Move to Mount Lebanon

The 5th century was a time of intense theological debate that fractured the Christian world. The pivotal Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD defined the dual nature of Christ as both fully divine and fully human. While many Eastern churches in the region (what would become the Syriac Orthodox and Coptic Churches) rejected this council’s decision, the followers of Saint Maron ardently defended it. This loyalty to Chalcedonian orthodoxy put them at odds with their neighbors and, at times, with the Byzantine Empire itself.

Facing persecution and seeking autonomy, the Maronites began a gradual migration from the plains of Syria into the formidable and protective embrace of Mount Lebanon. The rugged valleys and remote peaks, especially the sacred Qadisha Valley, became their fortress and their sanctuary. This geographical isolation was the key to their survival. It allowed them to preserve their unique faith and cultural identity, far from the direct control of the Byzantine emperors and, later, the successive Islamic Caliphates. It was in this mountain refuge that they solidified their structure, electing their first Patriarch, Saint John Maron, in the late 7th century, marking their formal organization as an autonomous church.

East Meets West: The Crusaders and Communion with Rome

For centuries, the Maronites remained a self-contained community in their mountain stronghold. Their story took a dramatic turn with the arrival of the European Crusaders in the 12th century. As the armored knights marched through the Holy Land, they were astonished to discover a thriving, organized Christian community that welcomed them as brothers in faith. For the Maronites, the encounter was equally profound.

What followed was not a conversion, but a formal reaffirmation of a bond the Maronites believe was never broken. They have always maintained that they never fell out of communion with the See of Rome. The isolation of the mountains had simply made regular contact impossible. The Crusades reopened that channel, and in 1182, the Maronites formally renewed their allegiance to the Pope.

This cemented their status as a “Middle Eastern anomaly.” They became an Eastern Catholic Church sui iuris—”of its own law.” This means they possess:

- An Eastern Liturgy: Their prayers, sacraments, and liturgical calendar are rooted in the ancient West Syriac tradition.

- A Unique Hierarchy: They are governed by their own Patriarch, who is elected by their synod of bishops and then requests communion from the Pope.

- Full Communion with Rome: They recognize the primacy of the Pope and are an integral part of the global Catholic Church.

This enduring link to the West would profoundly shape their destiny and the future of their homeland.

Architects of a Nation: The Maronites and Modern Lebanon

The Maronite connection with Rome, and by extension with Catholic Europe (particularly France), granted them a unique position during the long era of Ottoman rule. While other minorities were often marginalized, the Maronites of Mount Lebanon cultivated a degree of autonomy, developing their own social and political structures. This special status, however, was not without conflict, most notably the tragic 1860 civil war with their Druze neighbors, which prompted French intervention.

This intervention set the stage for the 20th century. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, France, acting as the mandatory power, carved out the state of “Greater Lebanon” in 1920. The borders were drawn specifically to create a country with a Christian majority, intended as a safe haven for the Maronites and other Christians in the Middle East. The Maronites were seen, and saw themselves, as the foundational stone of this new nation.

This role was codified in the 1943 National Pact, an unwritten agreement that established Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing system. Under this pact, the highest offices were distributed among the main religious groups:

- The President must be a Maronite Christian.

- The Prime Minister must be a Sunni Muslim.

- The Speaker of Parliament must be a Shia Muslim.

Thus, the Maronite Church, born from a hermit’s piety and forged in mountain isolation, became a central political actor and a defining force in the creation and governance of modern Lebanon.

A Resilient Legacy

From a small community of monks following an ascetic hermit to a global church that helped build a modern nation, the story of the Maronites is a testament to faith and resilience. They are a living bridge between East and West, a Syriac church that looks to Rome, and a deeply Lebanese community with a diaspora spread across the globe. In a region often defined by conflict and division, the Maronite Church stands as a remarkable monument to survival, adaptation, and the enduring power of a unique identity forged over centuries.