The story of Kongo and Portugal is a tragic epic. It begins with mutual respect and a remarkable cultural exchange, and ends with the disintegration of a great African kingdom, ravaged by the very forces it had initially welcomed. It serves as a powerful case study of the insidious nature of the transatlantic slave trade and its devastating impact on the continent.

A Sophisticated Kingdom on the Congo River

Long before the first European sails appeared on the horizon, the Kingdom of Kongo was a dominant power in West-Central Africa. Forged in the late 14th century, its heartland lay south of the Congo River, encompassing parts of modern-day Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Republic of the Congo. At its head was the Manikongo, an elected monarch who ruled from his capital city, Mbanza Kongo.

This was no simple village. Mbanza Kongo was a large, well-ordered urban center, the hub of a complex political system. The Manikongo presided over a council of advisors and governed a federation of provinces, each overseen by a governor he appointed. This structure allowed for efficient tax and tribute collection, the administration of justice, and the mobilization of a formidable army.

The kingdom’s economy was equally advanced. It was based on productive agriculture and skilled craftsmanship, particularly in textiles (made from raffia palm fiber), pottery, and metallurgy. The Kongo economy had its own currency—nzimbu shells, harvested from the island of Luanda and controlled by the Manikongo, giving him significant economic power.

An Encounter of Equals?

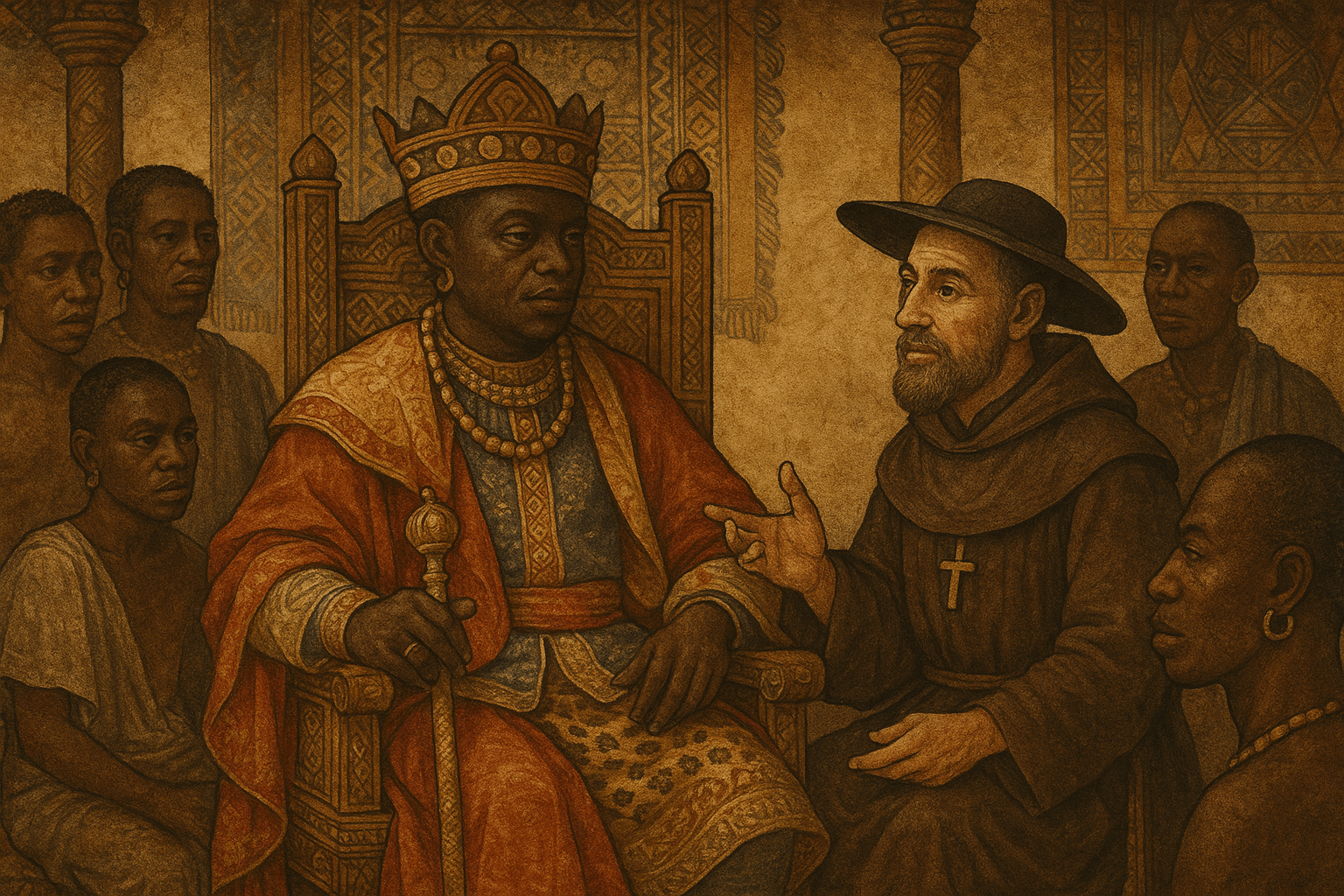

In 1483, the Portuguese explorer Diogo Cão arrived at the mouth of the Congo River. The initial contact was not one of conqueror and conquered, but of two powers sizing each other up. The Portuguese were impressed by the kingdom’s organization and wealth. The Manikongo at the time, Nzinga a Nkuwu, saw in the newcomers potential allies and access to new technologies, weapons, and what he perceived to be powerful spiritual knowledge: Christianity.

A diplomatic relationship was established. Hostages were exchanged not as prisoners, but as ambassadors to learn each other’s languages and customs. Kongo nobles traveled to Portugal and were received at the royal court, while Portuguese missionaries, soldiers, and artisans came to Mbanza Kongo. This was, for a fleeting moment, a unique experiment in cross-cultural partnership.

A Royal Conversion and a Christian Kingdom

The embrace of Portuguese culture reached its zenith under Nzinga a Nkuwu’s son, who, after a succession struggle, took the throne in 1509 and ruled for nearly 35 years as King Afonso I. While his father’s conversion to Christianity had been tentative (he was baptized as João I but later renounced the faith), Afonso was a zealous and devout Catholic.

Afonso saw Christianity and European knowledge as tools to modernize and strengthen his kingdom. He modeled his court on those of Europe, adopted Portuguese titles for his nobles, and made Catholicism the state religion. He renamed the capital Mbanza Kongo to São Salvador and financed the construction of numerous churches. More remarkably, he established literacy as a path to power, learning to read and write in Portuguese himself and corresponding directly with the kings of Portugal and the Pope in Rome.

Under Afonso’s rule, a fascinating syncretic culture emerged, blending Kongo traditions with Catholic Christianity. He was no puppet king; he was an active agent, selectively adopting European ideas to serve his own vision for Kongo’s future.

The Corrosive Influence of the Slave Trade

While Afonso pursued his project of Christian modernization, a darker economic force was gathering momentum. The initial trade with Portugal had involved luxury goods like copper and ivory in exchange for European items. Slavery existed in Kongo before the Portuguese, but it was a smaller-scale system involving war captives or criminals, who were often integrated into society. The Portuguese demand for enslaved people, however, was something entirely new and voracious, driven by the insatiable need for labor on the sugar plantations in Brazil and São Tomé.

At first, Afonso tried to control this trade, viewing it as a state monopoly where only captives from wars with neighboring, non-Christian peoples could be sold. But the profits were too immense. Portuguese merchants, along with renegade colonists, began to bypass the king’s authority. They armed provincial governors and rival claimants to the throne, encouraging them to wage wars for the sole purpose of capturing people to sell.

The situation spiraled out of control. Afonso’s letters to the King of Portugal from the 1520s are heartbreaking historical documents. He pleaded for help, writing:

“Each day the traders are kidnapping our people—children of this country, sons of our nobles and vassals, even people of our own family… This corruption and depravity are so widespread that our land is entirely depopulated.”

He lamented that his kingdom was being destabilized, his authority undermined, and his Christian project corrupted. His pleas went largely ignored. The economic engine of the slave trade was more powerful than the diplomatic niceties between kings.

Decline and Disintegration

The slave trade fatally weakened the Kingdom of Kongo from within. The Manikongo lost control over his own nobles, who became warlords enriched by selling their own people. The kingdom was plagued by civil wars and succession crises fueled by Portuguese interference.

The final blow came in 1665 at the Battle of Mbwila. A dispute over mining rights escalated into a full-scale war between the Kongo army and the Portuguese. The Manikongo António I led his forces personally, but the Portuguese army, armed with superior firearms and allied with rival African warriors, was victorious. António was killed and beheaded, and the Kongo army was shattered.

The Battle of Mbwila marked the effective end of Kongo as a unified, centralized state. The kingdom collapsed into a patchwork of smaller, warring territories, creating a vicious cycle where constant warfare fed the slave trade, which in turn fueled more conflict. São Salvador was abandoned and fell into ruin.

The story of the Kingdom of Kongo is a profound tragedy. It reveals an African political power that engaged with Europe on its own terms, but was ultimately consumed by the brutal economics of colonialism. It is a stark reminder that the history of Europe and Africa is not a simple monolith, but a complex tapestry of partnership, ambition, betrayal, and immense human suffering.