Imagine you’re a 10th-century warrior chieftain. You’ve just forged a powerful nomadic empire on the vast, windswept steppes of Manchuria. Your people are expert horsemen and archers, living a mobile life that follows the seasons and their herds. But through conquest, you now also rule over millions of settled farmers to the south. These people live in walled cities, tend rice and wheat fields, and have a thousand-year-old tradition of bureaucratic government, complex laws, and Confucian philosophy. How do you govern both? Do you force your warrior ethos on the farmers, risking rebellion and the collapse of the economy? Or do you adopt their settled ways, risking the loss of your own culture and martial prowess?

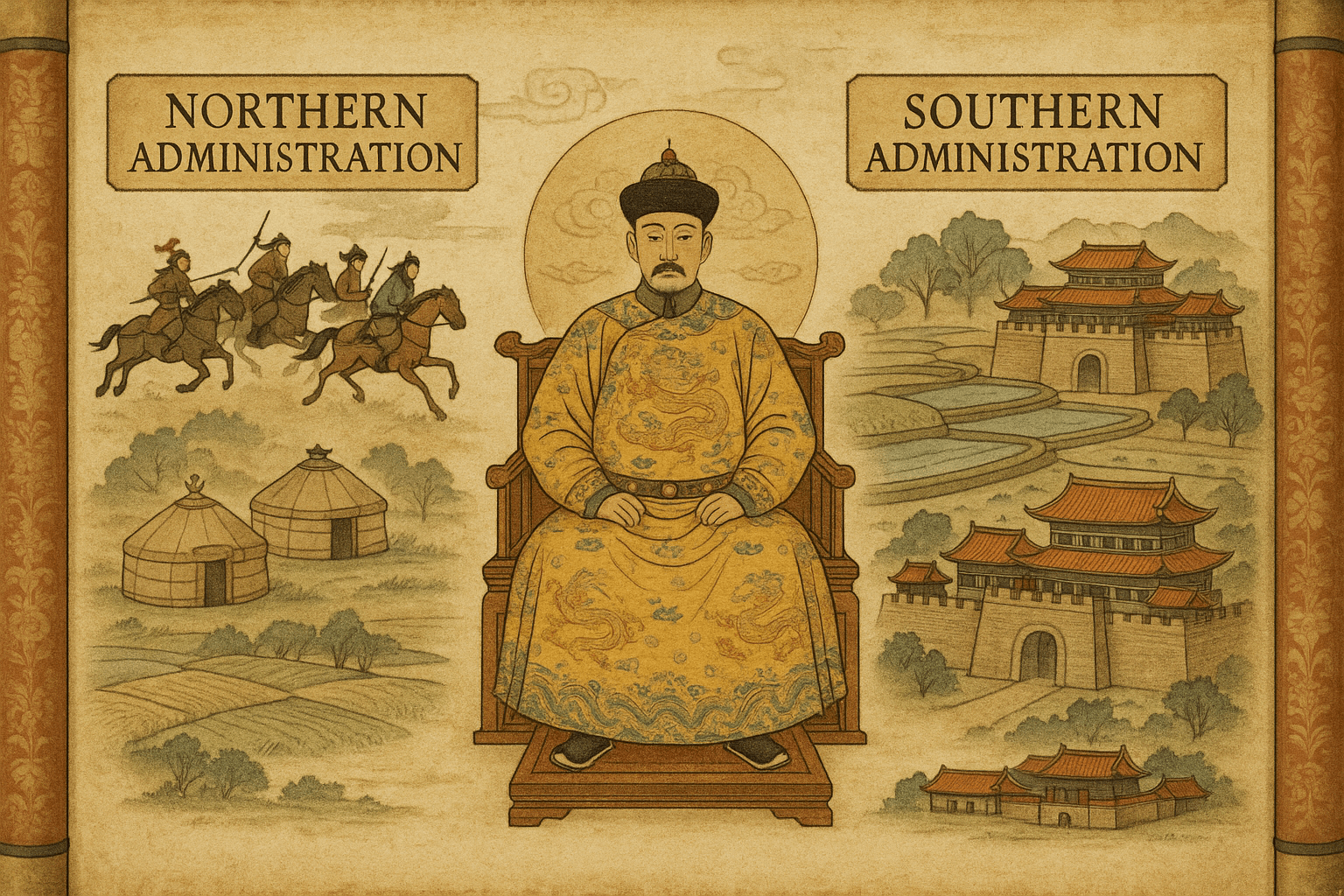

This was the profound challenge faced by Yelü Abaoji, the founder of the Khitan Liao Dynasty (907–1125 AD). His solution was a political masterstroke: a “Dual Administration” that allowed the Khitan to rule two vastly different societies simultaneously. This innovative system of governance was so effective that it became a blueprint for later, more famous conquest dynasties like the Mongols and the Manchus.

Who Were the Khitan?

Before they were emperors, the Khitan were a confederation of nomadic tribes roaming the lands of modern-day Mongolia, Northeast China, and the Russian Far East. For centuries, they were a formidable but fragmented force on the northern frontier of China’s Tang Dynasty. That changed in 907 AD when a charismatic leader, Yelü Abaoji, united the tribes and declared himself Khagan, or Great Khan.

Harnessing the formidable power of their cavalry, the Khitan expanded their territory, absorbing other nomadic groups and, crucially, pushing south to conquer settled agricultural lands, including a strategic slice of northern China. Abaoji established the Liao Dynasty, positioning himself not just as a tribal leader but as a legitimate Chinese-style emperor. He now had an empire of the “steppe and the sown”, encompassing two worlds that could not have been more different.

The Governance Dilemma: Steppe vs. Sown

The core of the Liao Dynasty’s problem was the stark contrast between its two major populations:

- The Northern Population: This was the Khitan heartland. It included the Khitan people and other allied nomadic tribes. Their society was organized around tribal allegiances, their economy was pastoral, and their law was customary and unwritten. Their greatest value was military strength, embodied by the mobile warrior.

- The Southern Population: This region, centered around the Southern Capital (today’s Beijing), was inhabited by Han Chinese and Bohai peoples. They had a sophisticated, sedentary society built on intensive agriculture. Their world was governed by a complex bureaucracy, detailed legal codes, and Confucian principles of civil administration and social hierarchy.

Applying a single system of government was impossible. Khitan tribal law was irrelevant to a Chinese farmer’s land dispute. A Chinese-style bureaucracy designed to manage tax registers and public works was ill-suited for managing nomadic herds and warriors. Forcing one culture’s system on the other would have been a recipe for disaster.

“One Dynasty, Two Systems”: The Genius Solution

The Liao leadership devised a brilliant system of parallel governments, effectively creating “One Dynasty, with Two Systems.” The administration was formally divided into a Northern and a Southern Chancellery, each designed to govern its respective population according to their own traditions.

The Northern Administration: Rule of the Steppe

The Northern Administration was the government for the Khitan, by the Khitan. Its structure was a sophisticated evolution of traditional tribal organization.

- Jurisdiction: Governed the Khitan and other nomadic peoples.

- Officials: Headed by the Northern Chancellor, with key positions filled almost exclusively by Khitan aristocrats.

- Law: Justice was administered based on Khitan customary law.

*Focus: Its primary concerns were military affairs, managing the Khitan tribes, and overseeing the pastures. It also managed the emperor’s personal retinue and mobile court, known as the ordo, which moved with the seasons in traditional nomadic fashion.

This system preserved the Khitan’s steppe-based identity and their critical military structure. It ensured that the warrior elite, the foundation of Liao power, remained under a familiar and effective system of command.

The Southern Administration: Rule of the Sown

The Southern Administration was a pragmatic adoption of established Chinese methods of governance. The Khitan were wise enough to know they shouldn’t reinvent the wheel when a perfectly good one was already spinning.

- Jurisdiction: Governed the settled Han Chinese and other agricultural populations.

- Officials: Headed by the Southern Chancellor and staffed primarily by educated Han Chinese scholar-officials, many of whom were recruited through a Liao-style civil service examination.

- Focus: Its purpose was civil administration. It collected taxes (in the form of grain and silk), managed agricultural production, maintained infrastructure like roads and canals, and oversaw a judiciary based on Chinese legal codes.

- Law: Applied the legal and administrative framework inherited from the Tang Dynasty.

This administration provided the economic engine for the empire. The taxes collected from the productive south funded the entire state, including the Khitan military. By allowing the Chinese to largely govern themselves according to their own traditions, the Liao minimized resentment and ensured stability and prosperity.

The Emperor: A Bridge Between Two Worlds

At the apex of this dual structure sat the Liao Emperor, who expertly embodied both identities. To his Khitan followers, he was the supreme military commander and Great Khan. To his Chinese subjects, he was the Son of Heaven, a legitimate Confucian-style ruler. The emperors maintained a mobile court that traveled through the northern territories for much of the year, hunting and living a nomadic lifestyle, but they also presided over the Southern Administration from their capital at Yanjing. This dual role was the linchpin that held the two disparate halves of the empire together.

The Enduring Legacy of Dual Administration

The Liao Dynasty’s system was a remarkable success, allowing a relatively small population of Khitan to rule a vast and diverse empire for over two centuries. While the dynasty eventually fell to the Jurchen people in 1125, its political innovation did not die with it.

The concept of a dual or parallel administration became a foundational model for subsequent conquest dynasties:

- The Jurchen Jin Dynasty, which conquered the Liao, adopted a similar model to rule their own mixed population.

- The Mongol Yuan Dynasty, faced with the immense task of ruling all of China, implemented a more complex but conceptually similar separation between the Mongol military elite and the Chinese civil bureaucracy.

- The Manchu Qing Dynasty, arguably the most successful conquest dynasty, perfected the model. They used the Manchu “Eight Banners” system to preserve their military and ethnic identity while employing a massive Han Chinese bureaucracy to administer the empire.

The Khitan may be a lesser-known name in world history than the Mongols or Manchus, but their political ingenuity was profound. By creating a system to rule both the steppe and the sown, they didn’t just build an empire—they created a blueprint for governance that would shape East Asia for the next 1,000 years.