A Viking Outpost on the Edge of the World

The story begins with one of the most famous Vikings: Erik the Red. Exiled from Iceland for manslaughter around 982 AD, he sailed west and found a vast, uninhabited land. In a brilliant feat of medieval marketing, he named the land “Greenland” to entice settlers to follow him. Around 985 AD, he led a fleet of 25 ships, with 14 successfully making the journey, to establish a new home.

Two main settlements took root: the larger Eastern Settlement in the south and the smaller Western Settlement further up the coast. For hundreds of years, they thrived. Archaeological remains paint a picture of a robust, complex society. They were farmers, raising hardy sheep, goats, and a limited number of cattle on coastal meadowlands. They were also hunters, pursuing caribou and seals to supplement their diet. Most importantly, they were traders. Their primary export was walrus ivory, a luxury good highly prized in Europe for art and ornamentation. In return, they received iron for tools, timber for shipbuilding, and ecclesiastical goods for their churches. They were not isolated barbarians; they were a self-aware European Christian society, complete with their own bishopric at Garðar in the Eastern Settlement.

The Cold Creeps In: The Climate Change Theory

The Norse arrived during a period known as the Medieval Warm Period, a time of relatively mild temperatures that made their pastoral lifestyle possible. But the climate is not static. Beginning in the 14th century, the North Atlantic region began to cool, entering what climatologists now call the “Little Ice Age.” For the Greenland Norse, this was a catastrophe in slow motion.

The evidence, drawn from ice cores and sediment analysis, is clear. The effects would have been devastating:

- Shorter Growing Seasons: Colder, shorter summers meant they could produce less hay to feed their livestock through the increasingly long and harsh winters. This would have led to widespread animal starvation and a collapse of their core food source.

- Advancing Sea Ice: Increased ice in the surrounding waters made seal hunting—a critical source of fat and calories—far more difficult and dangerous. It also made the sea voyage to and from Europe, their only lifeline, a much more perilous undertaking.

Climate change wasn’t an abstract concept; it was a relentless pressure squeezing the life out of their society, making every winter a greater struggle for survival than the last.

A Self-Inflicted Wound: Resource Depletion and Economic Collapse

The cooling climate was a massive external shock, but the Norse may have unwittingly made their situation worse. They were conservative farmers, applying European techniques to a landscape that could not sustain them. Over centuries, their livestock overgrazed the fragile meadows, leading to soil erosion. They chopped down the sparse woodlands of willow and birch for fuel and building materials, leaving the landscape barren and unable to regenerate.

At the same time, their economic foundation crumbled. The walrus ivory that paid for essential imports faced new competition. Cheaper elephant ivory from Africa and walrus ivory from Russia’s arctic regions began to flood the European market. As the value of their main export plummeted, the Greenlanders could no longer afford to import iron for tools, weapons, and nails, or the grain and timber they needed to maintain their way of life. Imagine a blacksmith unable to get iron or a farmer whose plough breaks with no way to repair it. This economic strangulation would have been just as deadly as the cold.

Strangers on the Shore: Interaction with the Inuit

The Norse were not alone in Greenland. By the 13th century, a new people were migrating south along the coast: the Thule, ancestors of the modern Inuit. The Norse called them “Skrælingar”, the same term they used for the Indigenous peoples of North America. The relationship between these two groups has long been a subject of debate.

Did violent conflict drive the Norse out? While some sagas hint at skirmishes, archaeological evidence for widespread warfare is scant. Instead of a direct war, the more likely scenario is one of competition. The Thule were masters of arctic survival. Their technology—kayaks, harpoons, dogsleds—was perfectly adapted for hunting seals and whales in the icy conditions of the Little Ice Age. The Norse, clinging to their European farming model, were at a terrible disadvantage. As their livestock died and their farms failed, the Norse were out-competed for the marine resources they both depended on by a people far better equipped to harvest them.

The Fading Connection: Abandoned by Europe

Perhaps the final blow was silence. By the 15th century, contact with Norway—Greenland’s parent state—became sporadic and then stopped altogether. Norway itself was weakened by the Black Death and political turmoil, and long-distance trade with a failing colony became a low priority. The last fully documented ship to return from Greenland arrived in Norway in 1410.

After that, the colony was on its own. There were no new settlers, no fresh supplies, no priests to man the churches, and no market for their goods. Cut off from the world they identified with, the Greenlanders were utterly isolated. Letters sent from the Pope in the late 1400s express concern about a diocese where no ship had landed in decades, but no rescue was ever mounted.

A Perfect Storm of Misfortune

So, what truly happened to the Greenland Norse? The answer is not a single, dramatic event, but a “perfect storm” of interconnected factors—a death by a thousand cuts.

The climate turned against them, undermining their entire way of life. Their own environmental practices weakened their ability to survive. Their economy collapsed, cutting them off from vital resources. They were out-competed by the better-adapted Thule people. And finally, Europe forgot them.

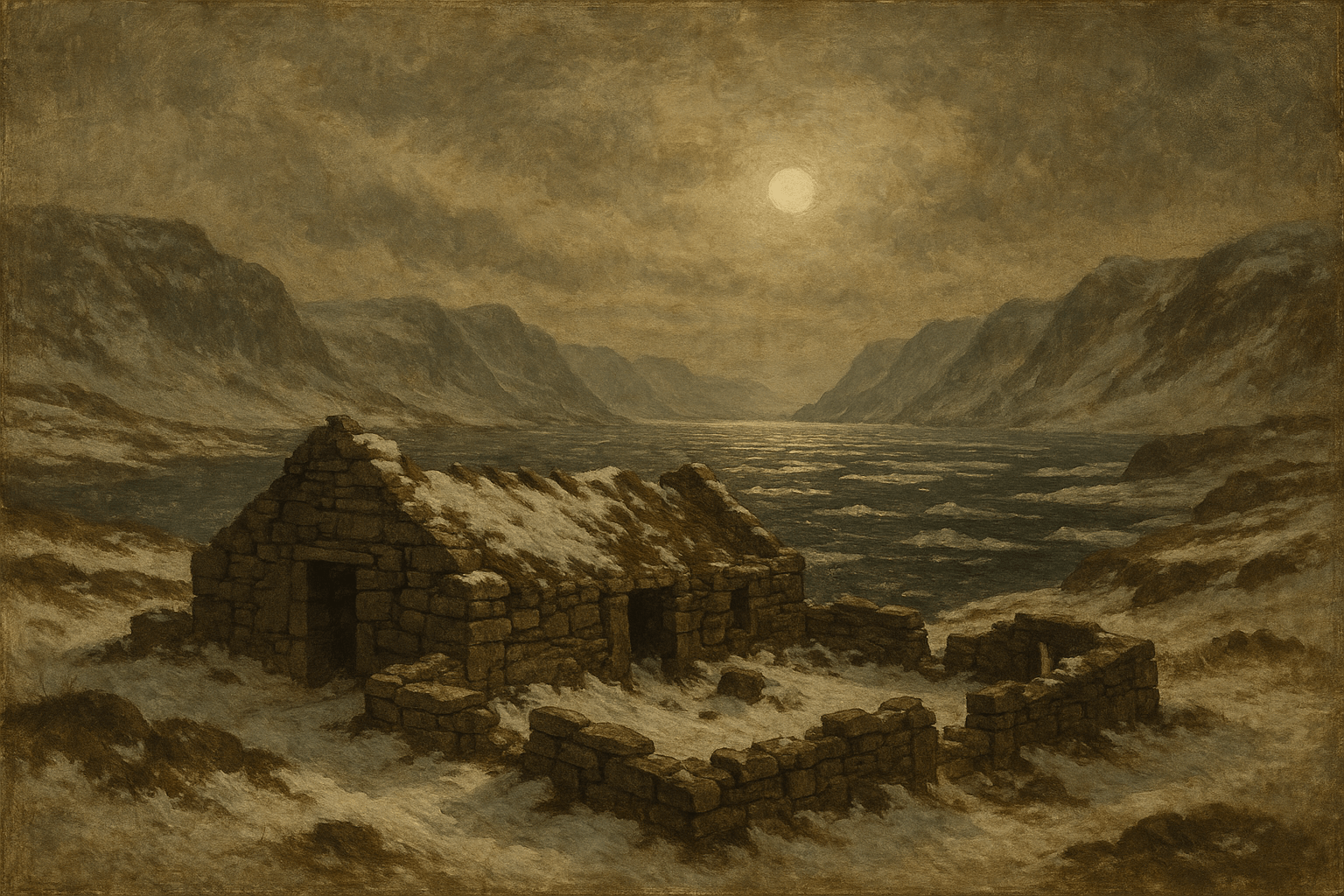

The end was likely not a sudden cataclysm, but a slow, grim dwindling over several generations. Some may have attempted to sail away, their fate unknown. Others may have been assimilated into Inuit communities, though genetic evidence for this is thin. Most likely, the population simply declined through starvation and disease, becoming too small to sustain itself until the last Norse Greenlander looked out over the ice-choked fjords, a lonely survivor of a lost world.