A World Lost: The Green Sahara

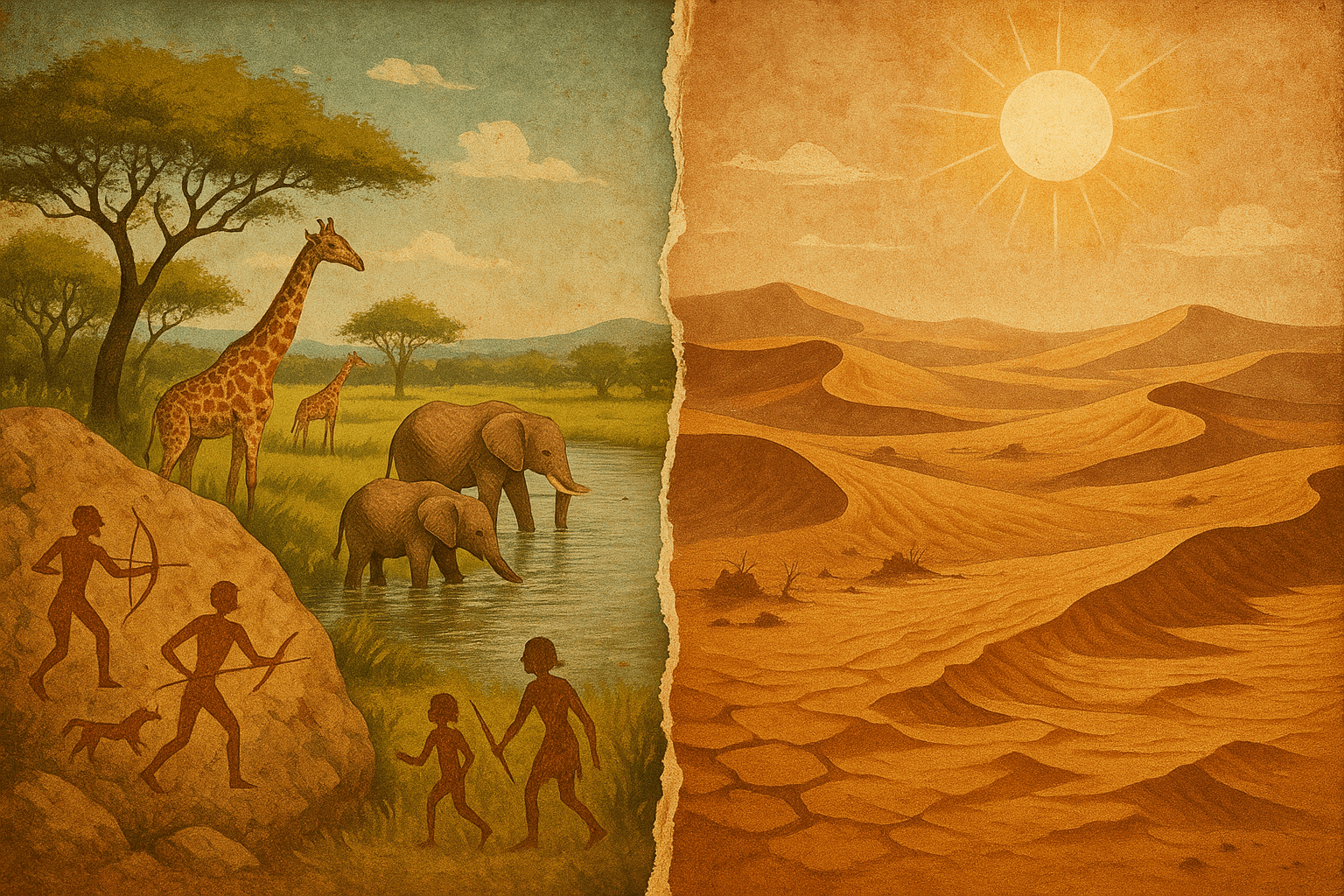

Between roughly 11,000 and 5,000 years ago, North Africa was unrecognizable. This era, known as the African Humid Period, saw the Sahara transformed into a lush grassland teeming with life. This wasn’t a desert with a few extra shrubs; it was a rich ecosystem capable of supporting an incredible diversity of megafauna. Herds of elephants, giraffes, rhinos, and hippos roamed where there is now only sand. Crocodiles swam in rivers that have long since vanished. The heart of the Sahara contained colossal bodies of water, the most famous being Lake Mega-Chad, a paleolake that at its peak was larger than the Caspian Sea, the world’s largest inland body of water today.

Evidence for this verdant past is etched into the very rock of the desert. In places like Tassili n’Ajjer in Algeria, stunning rock art galleries depict a world bustling with activity. We see detailed paintings of people hunting, herding long-horned cattle, and swimming in waters that no longer exist. One of the most famous images, found in the “Cave of Swimmers” on the Gilf Kebir plateau bordering Egypt and Libya, shows figures floating through water—a haunting testament to a completely different climate. This artistic record is backed by hard science: sediment cores drilled from old lakebeds reveal layers of pollen from grasses and trees, and the fossilized remains of fish and crocodiles confirm the presence of permanent water sources.

The people who lived in this paradise were sophisticated hunter-gatherers and, later, some of the world’s earliest pastoralists. They developed complex societies, created the first known pottery in Africa, and thrived on the abundance the land provided. For six millennia, the Green Sahara was the cradle of vibrant cultures.

The Great Drying: A Climatic Tipping Point

So, what happened? How did a sprawling savanna turn into the world’s largest hot desert? The answer lies not on Earth, but in the sky. The Green Sahara was a product of the Earth’s natural orbital cycles, specifically a wobble in its axis known as precession. This slow, 23,000-year cycle changes the time of year that Earth is closest to the sun.

During the African Humid Period, the Northern Hemisphere was tilted toward the sun during the summer solstice, receiving significantly more solar radiation. This intensified the heating of the land, which in turn strengthened the West African Monsoon. Powerful, moisture-laden winds were pulled much farther north than they are today, delivering life-giving rain deep into the heart of the Sahara. The desert bloomed.

But around 5,500 years ago, the orbital mechanics began to reverse. As the Earth’s wobble continued its inexorable cycle, solar radiation in the Northern Hemisphere summer began to weaken. The engine driving the powerful monsoon sputtered. The rains began to fail and retreat south. Scientists debate the speed of this transition. Some evidence suggests a gradual drying over a thousand years, while other studies point to a much more terrifying scenario: a rapid climatic collapse that occurred in as little as one or two centuries. For the people living there, it must have felt like the end of the world as the familiar landscape withered and blew away before their very eyes.

An Exodus Written in Sand: Human Migration and Adaptation

As the lakes dried up and the grasslands turned to sand, the Green Sahara could no longer support its large populations. The flora and fauna vanished, and humans were faced with a stark choice: adapt or leave. What followed was one of the largest, most prolonged human migrations in our species’ history—a multi-generational exodus driven by climate change.

Archaeological evidence shows settlements being abandoned across the entire region. The once-thriving communities were forced to follow the retreating rains and seek refuge in more hospitable lands. This movement wasn’t random; it followed clear geographical pathways:

- Eastward to the Nile Valley: One of the most significant streams of migration was towards the Nile River. This perennial river offered a reliable, life-sustaining ribbon of green in an increasingly arid world.

- Southward to the Sahel: Other groups moved south, following the retreating monsoon into the semi-arid Sahel belt and the more tropical regions of West and Central Africa.

This wasn’t just a relocation; it was a profound social and cultural upheaval. People who had lived for generations in a land of plenty were now climate refugees, forced to find new homes and new ways of life in lands that were often already inhabited.

The Legacy of the Green Sahara: Forging New Civilizations

The end of the Green Sahara was a catastrophe, but it was also a powerful catalyst for cultural innovation and the formation of new societies. The forced migration fundamentally reshaped the demographic and cultural map of Africa, with consequences that echo to this day.

Perhaps the most famous result was the rise of Pharaonic Egypt. While civilization had been developing in the Nile Valley for centuries, the sudden influx of diverse peoples from the drying western desert provided a critical stimulus. These migrants brought their Götter, their cultural memories, and most importantly, their pastoralist knowledge of cattle herding. The concentration of population in the narrow, fertile corridor of the Nile created the social density and cultural dynamism necessary for the emergence of a complex, unified state. It is no coincidence that the consolidation of the Egyptian state under the first pharaohs around 3100 BCE happened as the Sahara’s desiccation reached its peak.

To the south, the migrants who filtered into the Sahel and West Africa disseminated their knowledge of pastoralism and agriculture, contributing to the genetic and linguistic diversity of the region. These new populations laid the groundwork for the great Sahelian empires, like Ghana, Mali, and Songhai, that would rise centuries later.

The story of the Green Sahara’s end is a powerful, prehistoric reminder of the profound link between climate, environment, and human history. It demonstrates how dramatically our world can change and how resilient and adaptable humanity can be in the face of environmental collapse. The vast, silent desert is not an empty void; it is a landscape haunted by the memory of a lost world, whose disappearance set in motion the very currents of history that shaped the continent of Africa.