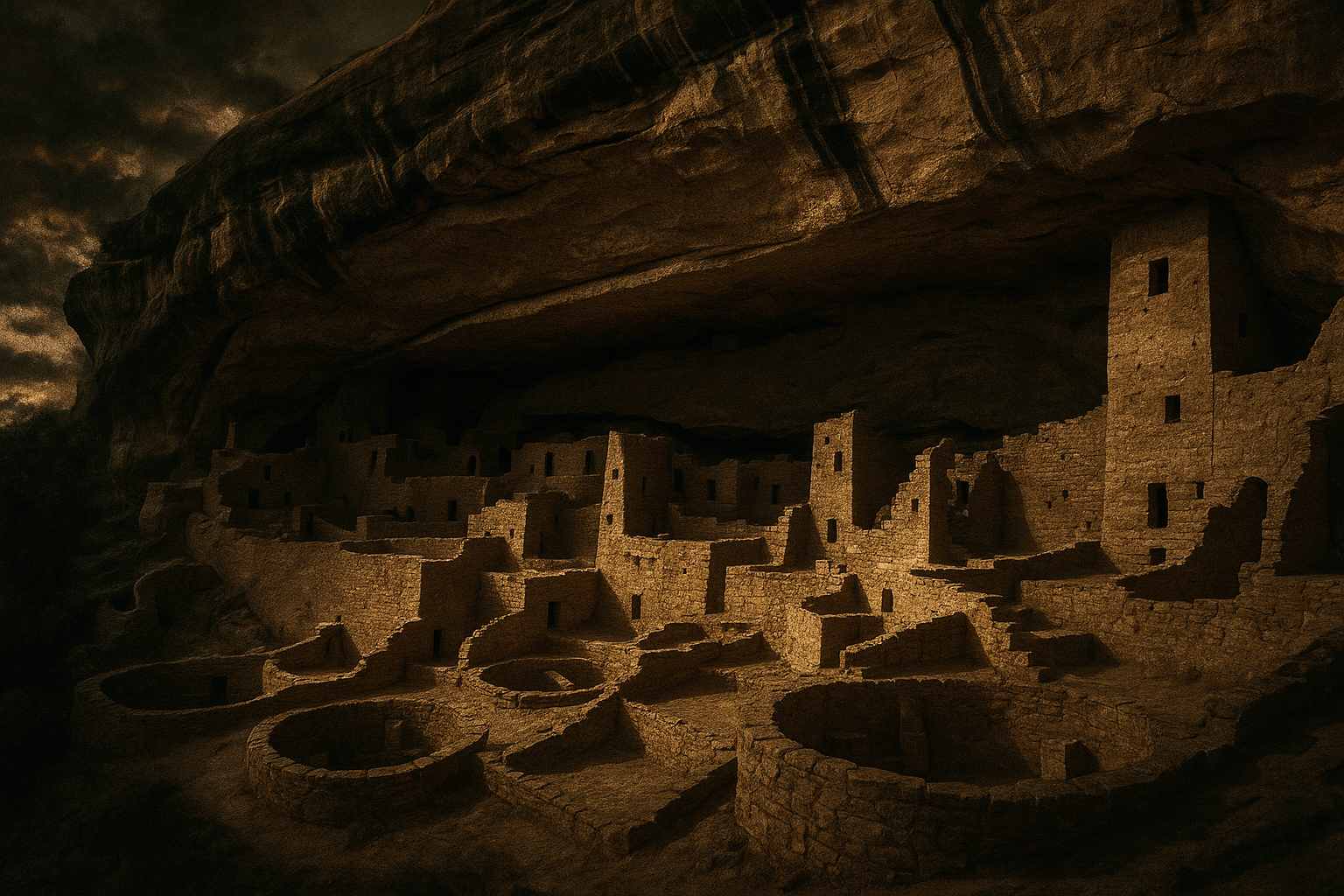

Imagine standing at the edge of a canyon in the American Southwest, gazing across at a city carved directly into the cliff face. Multi-story stone towers, interconnected rooms, and ceremonial kivas form a breathtaking architectural marvel. This is a place like Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace or the sprawling pueblos of the Kayenta region—centers of a vibrant civilization. For centuries, these communities thrived, home to thousands of Ancestral Pueblo people. Then, in the span of just a few decades around 1300 CE, they were gone. The plazas grew silent, the homes emptied, and the fields lay fallow. It was not a gradual decline but a mass exodus, an event a historian once called “one of the greatest vanishing acts in human history.” But the people didn’t vanish. They left. The enduring question is: why?

A Society at its Peak

To understand the abandonment, we must first appreciate what was abandoned. By the 1200s, the Ancestral Puebloans had created one of North America’s most sophisticated pre-Columbian cultures. In the Four Corners region (where Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah meet), they had perfected dry-land farming, cultivating maize, beans, and squash with intricate water management systems. Their black-on-white pottery was a widespread and valued trade good, and their knowledge of astronomy was woven into their architecture, with buildings aligned to solstices and equinoxes.

The settlements were impressive. While the massive great houses of Chaco Canyon had seen their influence wane a century earlier, regional centers like Mesa Verde were at their zenith. Thousands of people lived in complex, densely packed communities, either in large villages on mesa tops or within the stunning, defensive alcoves of cliff dwellings. Life was stable, organized, and deeply connected to the landscape and the seasons. Yet this very stability was balanced on a knife’s edge, utterly dependent on a predictable climate in an unforgiving environment.

The Climate Culprit: The Great Drought

The most widely accepted and scientifically supported theory for the great migration points to the climate. Through the science of dendrochronology (the study of tree rings), researchers have pieced together a detailed climate history of the Southwest. The data reveals a devastating, prolonged period of cold and drought that gripped the region from approximately 1276 to 1299. Dubbed the “Great Drought”, this wasn’t just a few dry years; it was more than two decades of failed rains.

For a society built on agriculture, the consequences were catastrophic.

- Crop Failure: Maize harvests would have dwindled and eventually failed entirely, leading to severe food shortages and widespread malnutrition. Skeletal remains from this period show evidence of anemia and other stress indicators.

– Water Scarcity: Springs and streams dried up, forcing people to travel farther for this essential resource. The intricate reservoir systems that had sustained them for generations were rendered useless.

– Resource Depletion: As the drought wore on, the environment’s carrying capacity collapsed. Game animals grew scarce, and forests were thinned for fuel and building materials, further degrading the land.

The Great Drought was a powerful “push” factor. It made life in the Four Corners region, particularly at the high elevations of Mesa Verde, physically unsustainable. The land that had nourished their ancestors for centuries could no longer support them.

More Than Just a Lack of Rain: Social and Political Unraveling

While the Great Drought provides a compelling explanation, many archaeologists argue it’s only part of the story. Human societies have faced environmental challenges before. Why was this one so final? The answer may lie in the social fabric of the Ancestral Puebloan world.

The environmental stress likely ignited intense social and political strife. With dwindling resources, competition for what little food and water remained would have become fierce. Archaeological evidence from the late 1200s points to a sharp increase in violence. We see signs of burned villages, defensive walls hastily erected around communities, and skeletal remains bearing the marks of violent conflict. Some sites, like Sand Canyon Pueblo in Colorado, reveal evidence of a brutal final battle and massacre.

This internal conflict suggests a breakdown of the social systems that had previously managed disputes and facilitated trade. Leadership, which may have been based on the ability to ensure agricultural and ceremonial success, would have lost its authority as the rains failed and people starved. The social glue that held these large communities together was dissolving under immense pressure.

A Crisis of Faith and the Pull of a New Order

For the Ancestral Puebloans, religion was not separate from daily life; it was interwoven with farming, the weather, and the cosmos. Their ceremonies were designed to maintain harmony with the spiritual world and ensure the timely arrival of the rains that sustained them. When those rains failed for over twenty years, it wasn’t just an agricultural crisis—it was a spiritual one.

The prolonged drought and ensuing social chaos could easily have been interpreted as a sign that the old rituals had failed or that the deities had abandoned the people. This crisis of faith may have opened the door for new religious ideas spreading from the south. Many scholars believe the migration coincided with the rise of the Katsina (or Kachina) belief system. This new religious movement, with its focus on masked spirit dancers who act as intermediaries with the gods, may have offered a renewed sense of hope and a different way of relating to the world.

This new ideology could have acted as a powerful “pull” factor. Instead of just being pushed from their homes by disaster, the people may have been actively drawn toward new lands and new communities to the south and east, where this new religious system was taking root. The promise of a new social and spiritual order was a powerful incentive to leave the failing world behind.

The Great Migration: A Story of Resilience

So where did they go? The Ancestral Puebloans migrated south and east, following the rivers and seeking more reliable sources of water. They moved into the Rio Grande valley in present-day New Mexico and to the Hopi Mesas and Zuni region of Arizona. This was not a single, organized journey but a series of movements by different groups over several decades.

When they arrived, they did not simply recreate their old communities. They founded new pueblos, often organized in different ways that reflected their new social and religious ideas. These migrations led to an incredible aggregation of people and a fusion of cultures, giving rise to the vibrant Pueblo societies that greeted the Spanish centuries later and that still exist today.

The “Great Pueblo Abandonment”, therefore, is poorly named. It was not a mysterious disappearance but a strategic and courageous act of migration. Faced with a perfect storm of environmental collapse, social violence, and spiritual crisis, the Ancestral Puebloans made a deliberate choice to move on. They left their magnificent stone cities behind, but they carried their culture, their skills, and their lineage with them. Their legacy is not found only in the silent ruins that captivate us today, but in the living traditions, languages, and resilience of their direct descendants: the Pueblo people of the American Southwest.