A City Drowned in Sweetness

It was an unseasonably warm winter day. Near Keany Square on Commercial Street, a massive, 50-foot-tall steel storage tank stood ominously over the waterfront neighborhood. Owned by the Purity Distilling Company, a subsidiary of United States Industrial Alcohol (USIA), the tank held a vast quantity of molasses destined for fermentation into industrial alcohol—a key component in the manufacture of munitions for World War I. Just after 12:30 PM, as residents sat down for lunch, disaster struck without warning.

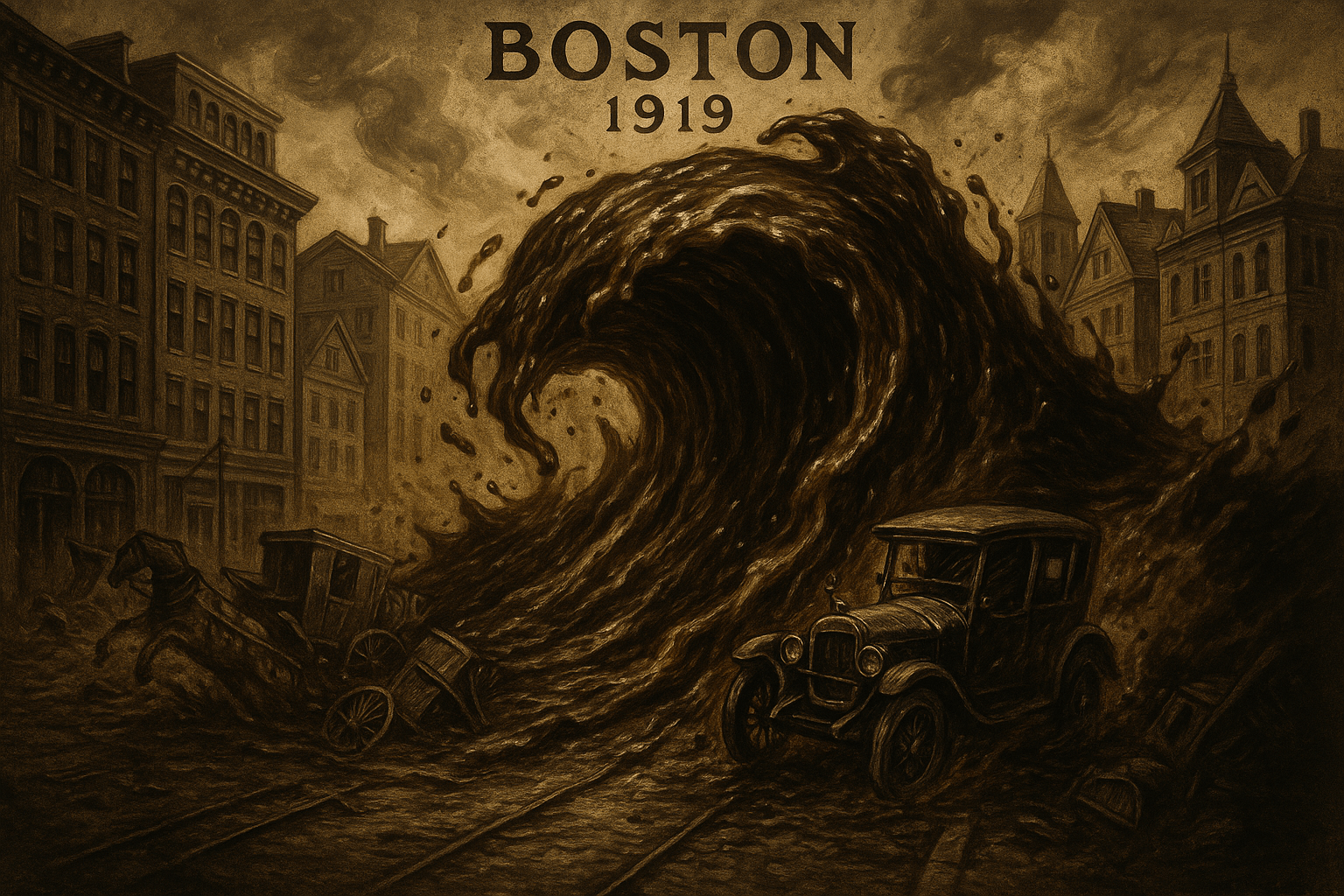

Witnesses reported hearing a deep, rumbling groan, followed by a sound like machine-gun fire as the tank’s steel rivets shot out like bullets. The colossal structure failed catastrophically. In an instant, a monstrous, 25-foot-high wave of dark, viscous liquid erupted, moving at an estimated 35 miles per hour. The sheer force of the wave was immense. It ripped a nearby firehouse from its foundation, crushed a portion of the elevated railway tracks, and flattened buildings. The air, suddenly thick with a sickeningly sweet smell, was filled with the wrenching sounds of twisting metal and the screams of those caught in the tide.

The Human Cost of a Sticky Tide

The molasses flood was not a gentle ooze; it was a destructive force of nature created by man. Its immense pressure and density made it a killer. People, horses, and wagons were swept up and crushed against debris. For those who survived the initial impact, a far more horrifying fate awaited. The cooling winter air quickly thickened the molasses into a thick, inescapable glue.

Rescuers who rushed to the scene found themselves wading through a waist-deep morass that clung to their boots and hampered every step. They heard the faint cries of victims trapped under wreckage or slowly suffocating in the dark goo. In total, 21 people lost their lives, from a 10-year-old boy collecting firewood to a blacksmith working in his shop. Another 150 were seriously injured. The sight was surreal: a modern cityscape transformed into a prehistoric tar pit, with rescuers working frantically against an enemy that was both a liquid and a solid.

A Recipe for Disaster: Corporate Negligence

How could a simple storage tank fail so completely? As investigators would later discover, the Great Boston Molasses Flood was not a freak accident; it was an inevitability born from corporate greed and abysmal engineering practices. The tank was a textbook case of cutting corners.

- Rushed Construction: The tank was erected in 1915 in a hurry to meet the wartime demand for industrial alcohol.

- Insufficient Testing: A fundamental safety test for such a structure is to fill it with water to check for leaks and structural integrity. USIA’s tank was never tested with water. The company simply began pumping molasses into it.

- Obvious Flaws: From the moment it was first filled, the tank leaked. It leaked so badly that local children would bring cups and buckets to collect the sweet drippings. Instead of addressing the structural flaws, USIA simply painted the tank brown to hide the dark streaks of molasses running down its sides.

- Lack of Expertise: The man tasked with overseeing its construction, Arthur Jell, was not an engineer or an architect. He was a finance man who couldn’t even read blueprints. In his reports, he noted that he saw the tank “swell and contract” as it was filled and emptied but did not recognize this as a sign of extreme metal fatigue.

The final straw likely came two days before the disaster. A fresh, warm shipment of molasses was pumped into the tank, mixing with the older, colder mass already inside. The resulting thermal stress, combined with the ongoing fermentation that produced carbon dioxide gas, created more pressure than the shoddily built, fatigued steel walls could withstand.

The Long, Slow Cleanup

The immediate rescue effort quickly turned into a monumental cleanup operation. Removing over two million gallons of sticky, hardening molasses was a nightmare. Fire crews initially tried to wash it away with high-pressure hoses, but this was largely ineffective. They soon discovered that saltwater was a better solvent and began pumping water from the harbor to spray down the streets, buildings, and everything else caked in brown sludge. The mixture flowed into the harbor, turning the water brown for months.

The cleanup took over 80,000 man-hours. For decades after the flood, Bostonians claimed that on hot summer days, the faint, sweet smell of molasses still lingered in the North End—a ghostly reminder of the tragedy.

A Landmark Case and a Lasting Legacy

In the aftermath, Purity Distilling’s parent company, USIA, tried to deflect blame. Their official explanation was that the tank had been blown up by anarchists or saboteurs, a common fear in post-WWI America. The victims and their families, however, filed a class-action lawsuit against the company—one of the first of its kind in Massachusetts history.

The resulting three-year legal battle was a turning point for public safety law. The court appointed an auditor, Colonel Hugh W. Ogden, who conducted an exhaustive investigation. After interviewing thousands of witnesses and consulting with expert metallurgists and engineers, Ogden issued a definitive report: the tank had collapsed under the weight of its own structural failings. There was no bomb. The disaster was caused entirely by corporate negligence.

USIA was found liable and forced to pay out settlements equivalent to about $7 million in today’s money. More importantly, the disaster spurred widespread reform. The tragedy of the Great Molasses Flood led directly to the passage of laws in Massachusetts and across the United States requiring that all plans for major construction projects be signed and sealed by a licensed engineer and filed with public authorities. Building permits and inspections became mandatory. The bizarre event highlighted the dire need for professional oversight and forced the country to take engineering standards seriously, ensuring that public safety would not be so easily sacrificed for profit.

The story of the Great Boston Molasses Flood remains one of history’s strangest footnotes. But beneath its absurd surface lies a serious lesson about responsibility, regulation, and the human cost of cutting corners. It was a tragedy that, quite literally, stuck, leaving a legacy that makes our modern world fundamentally safer.