From Blacksmiths to Khans: The Rise of the Ashina Clan

Our story begins in the mid-6th century CE. The immense grasslands of Inner Asia were under the thumb of the Rouran Khaganate, a powerful nomadic confederation. Among their vassals was a tribe known for its exceptional metalworking skills, living in the Altai Mountains. This tribe, led by the charismatic Ashina clan, would soon be known to the world as the Göktürks.

According to their foundational myth, the Ashina were the sole survivors of a massacre, saved only when a she-wolf discovered a wounded young boy and nursed him back to health in a hidden mountain cave. This wolf would become the sacred ancestor of the Turkic Khagans, a powerful symbol of their resilience and divine mandate to rule.

Historically, the Ashina clan served the Rouran as blacksmiths. This was no lowly profession; in a world where military power depended on superior weapons and armor, control over iron production was a strategic asset. In 552 CE, the leader of the Ashina, Bumin, felt strong enough to demand a Rouran princess in marriage. The Rouran ruler scoffed at the request, reportedly sending back the insulting message: “You are my blacksmith slave. How dare you utter such words?”

This insult was the spark that ignited the steppe. Bumin forged an alliance with the Western Wei dynasty in northern China, and in a swift campaign, he shattered the Rouran forces. He declared himself “Il-Khagan” (Khagan of the Realm), establishing the First Turkic Khaganate. He had turned his mastery of iron into an empire of steel.

An Empire on Two Fronts: The Eastern and Western Khaganates

Bumin’s reign was tragically short; he died within a year of his great victory. In keeping with steppe tradition for managing vast territories, the khaganate was divided.

- The Eastern Khaganate, the senior branch, was based in the traditional heartland of the Otuken forest (in modern Mongolia) and ruled by Bumin’s successors.

- The Western Khaganate was governed by Bumin’s younger brother, the formidable and long-reigning Istämi. His domain expanded relentlessly westward, eventually encompassing the wealthy oasis cities of Central Asia and stretching all the way to the Caspian and Black Seas.

While theoretically one empire, this dual administration created two distinct spheres of influence. The East dealt primarily with the politics of China, while the West became a major player in the affairs of Persia and the Byzantine Empire.

Controlling the World’s Oldest Highway: The Silk Road

The Göktürk empire wasn’t just a mobile military force; it was strategically positioned astride the most lucrative trade network of the ancient world: the Silk Road. By controlling the artery that connected the Mediterranean world with China, the Göktürks held the keys to immense wealth and geopolitical influence.

The Western Khagan, Istämi, proved to be a particularly shrewd diplomat. The primary obstacle to his full control of the silk trade was the Sassanian Empire of Persia, which acted as a middleman and siphoned off profits. Seeking to bypass them, Istämi sent an embassy led by a Sogdian merchant named Maniakh on an epic journey. They traveled past Persia, across the Caucasus, and over the Black Sea, arriving in Constantinople around 568 CE. This bold move established a direct Göktürk-Byzantine alliance against their common Sassanian rival, a stunning example of long-distance diplomacy in the 6th century.

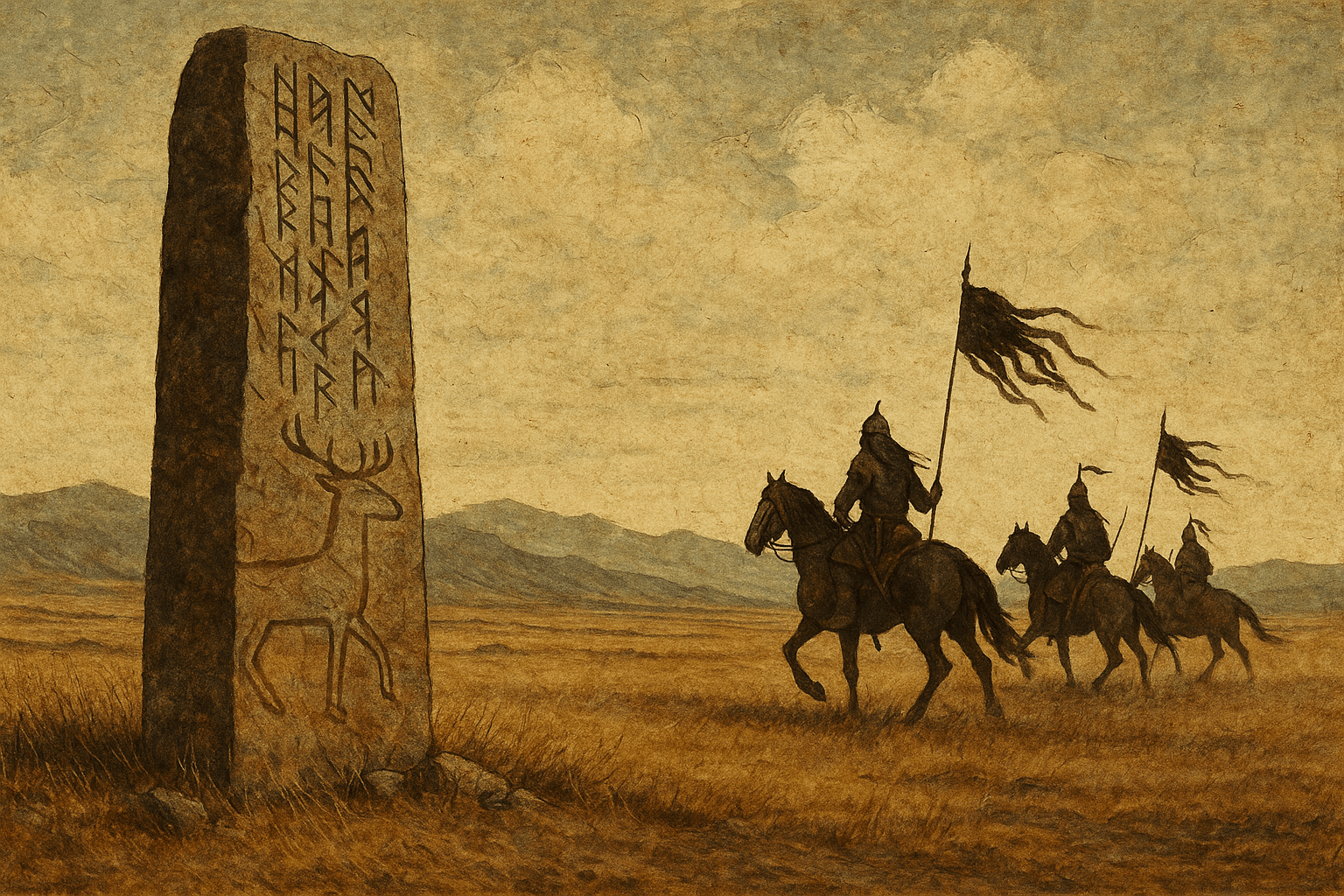

A Voice Carved in Stone: The Orkhon Script

Perhaps the most incredible legacy of the Göktürks is that they speak to us directly from the past. They developed the Old Turkic script, also known as the Orkhon script—the first known writing system for any Turkic language. Carved onto monumental stone stelae in the Orkhon Valley of Mongolia, these inscriptions are a window into the Turkic soul.

The most famous of these, the Orkhon Inscriptions, were erected in the early 8th century during the Second Turkic Khaganate, but they carry the cultural DNA of the first. In them, rulers like Bilge Khagan recount their history, dispense wisdom, and issue stern warnings to their people. One famous passage stands as a timeless testament to the complex relationship between steppe nomads and settled civilizations:

“The words of the Chinese people have always been sweet and the materials of the Chinese people have always been soft. Deceiving with sweet words and soft materials, the Chinese are said to cause the remote peoples to approach them in this manner… After you have settled close to them, O Turkic people, you fall into their traps. A wise man who is tricked by their sweet words and fine silks is doomed.”

These inscriptions are not just historical records; they are the founding documents of Turkic political identity, expressing a clear sense of “us” versus “them” and the duties of a ruler to his people.

The Dragon and the Wolf: A Complex Dance with Tang China

No relationship was more consequential for the Göktürks than the one they shared with China. The reunified and powerful Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) viewed the Turkic khaganate as its primary existential threat. The relationship was a volatile mix of war, trade, tribute, and diplomacy.

In 626 CE, shortly after Emperor Taizong took the throne, the Eastern Göktürk Khagan led a massive army to the gates of the Tang capital, Chang’an. In a moment of high drama, the young emperor had to ride out and personally negotiate a humiliating treaty on the Wei River bridge, agreeing to pay a hefty tribute to get the Göktürks to withdraw. However, the Tang were masters of long-term strategy. They expertly exploited internal divisions within the Ashina clan, propping up rival claimants and using their economic power to sow discord. By 630 CE, Emperor Taizong had his revenge, conquering the Eastern Khaganate. The Western Khaganate held out longer but fell to Tang campaigns by 657 CE, bringing the First Turkic Khaganate to an end.

The Legacy of the First Turks

Though their first empire collapsed under Chinese pressure, the Göktürk model proved indestructible. A successful rebellion in 682 CE led to the Second Turkic Khaganate, a direct revival of the first. More importantly, the Göktürks established a political and cultural template that would be copied and adapted by successive steppe peoples for centuries.

This blueprint for empire included:

- The supreme title of Khagan (Khan of Khans).

- The concept of a ruling clan with a heavenly mandate to rule.

- A dual east-west administrative structure for governing vast lands.

- A distinct Turkic identity, solidified by a common language and script.

From the Uyghurs and Khazars to the Seljuks and Ottomans, the echoes of Göktürk statecraft are unmistakable. Even the Mongol Empire, in its organization and ambition, bore a striking resemblance to the great Turkic power that had preceded it. The Göktürks were more than just raiders; they were state-builders, diplomats, and chroniclers who defined what it meant to rule the steppe and left an indelible mark on the history of the world.