For over a century, these descendants of the Mongol empire forged a powerful state that not only terrified their neighbors but also represented a fascinating evolution of the steppe warrior tradition. Before their tragic and brutal end, the Dzungars were the last great nomadic power to challenge the mighty sedentary empires of their day, marking the fiery conclusion to a two-thousand-year-old historical epic.

A New Power in the East

The Dzungars emerged in the early 17th century from a confederation of Oirat Mongol tribes in the region known as Dzungaria—a basin of deserts and mountains corresponding roughly to northern Xinjiang in modern-day China. While other Mongol groups had submitted to the rising Manchu-led Qing Dynasty, the Oirats remained fiercely independent.

Under ambitious leaders like Khara Khula and his son Baatur Khungtaiji, the Dzungars began consolidating their power. They weren’t just a loose collection of raiding tribes; they were building a state. They established a capital at Gulja, created a legal code, and fervently promoted Tibetan Buddhism as a unifying cultural and political force. This wasn’t merely a revival of the old Mongol ways; it was an attempt to create a modern, centralized nomadic empire capable of competing in a new world.

The Gunpowder Empire: Military and State Innovation

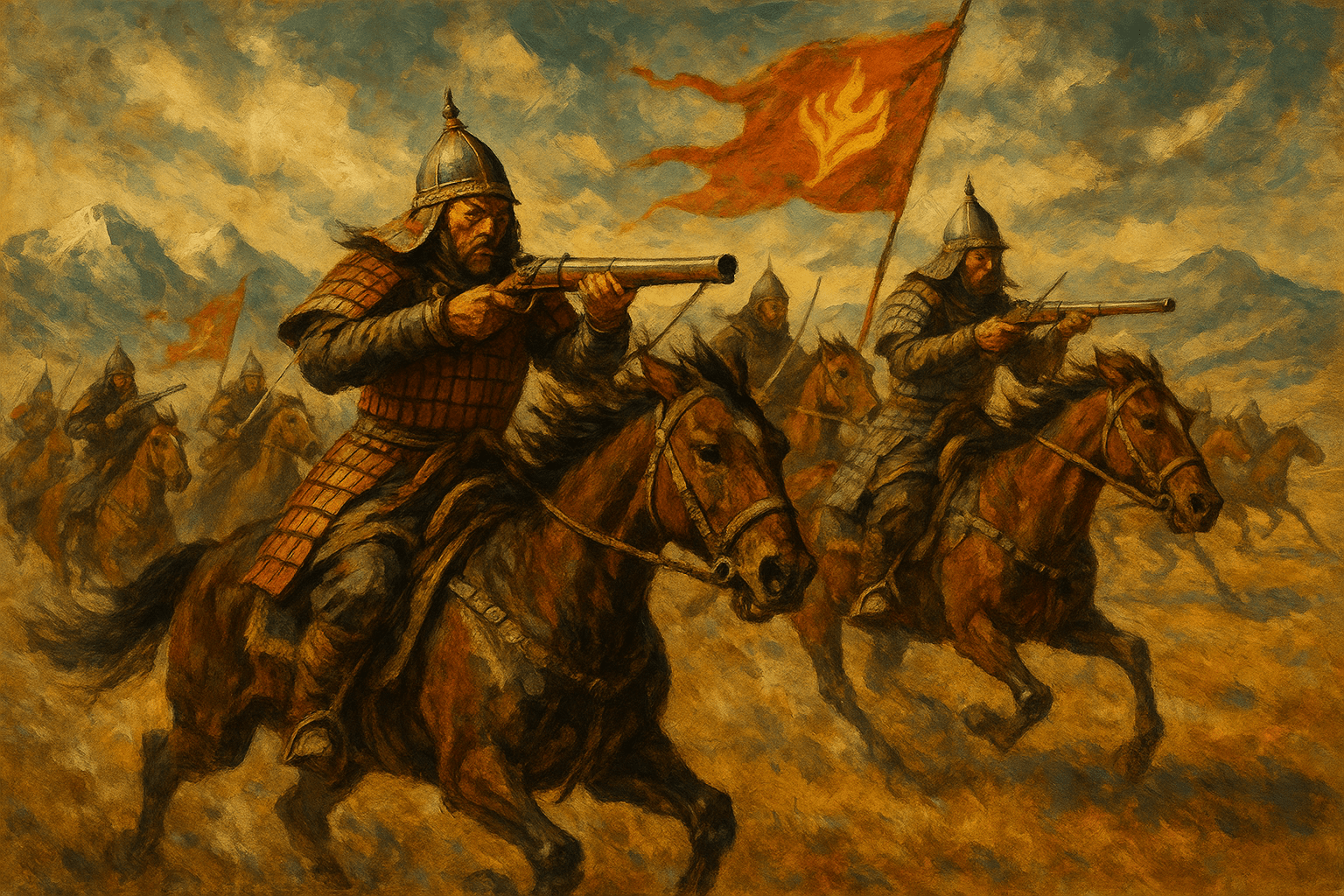

What truly set the Dzungar Khanate apart and made it such a grave threat to its neighbors was its remarkable synthesis of tradition and innovation. They didn’t reject their heritage as horse archers; they enhanced it with the very technology that was making sedentary empires so powerful.

Unlike previous steppe peoples, the Dzungars wholeheartedly embraced gunpowder. They understood that bows and arrows alone could no longer win the day against disciplined infantry armed with muskets and supported by artillery. So, they decided to fight fire with fire. The Dzungars achieved something extraordinary for a nomadic society:

- Domestic Arms Industry: They established centers for mining iron and copper, and developed their own arms manufacturing. They began producing high-quality matchlock muskets on a large scale.

- Mastery of Artillery: The Dzungars didn’t just have guns; they had cannons. They fielded camel-mounted light cannons called zamburaks, which gave their highly mobile armies devastating firepower. They even learned casting techniques from captured foreigners, including Swedish soldiers from a defeated Russian army.

- A Hybrid Army: A Dzungar army was a fearsome sight. It combined the classic steppe advantages of mobility and horsemanship with disciplined units of musketeers and a formidable artillery train. They could outmaneuver and outshoot their opponents, a lethal combination that baffled their foes.

This military prowess was supported by a sophisticated state that also encouraged agriculture and controlled vital segments of the old Silk Road trade routes. They were a semi-sedentary empire, financing their modern army through both traditional nomadic pastoralism and settled economic activities. This made them rich, resilient, and incredibly dangerous.

Clash of Titans: The Dzungar-Qing Wars

The rise of the Dzungar Khanate set it on a collision course with another expanding empire: the Qing Dynasty of China. For nearly 70 years, these two powers were locked in a titanic struggle for control of Inner Asia. This wasn’t a simple case of a sedentary state crushing nomads; it was a war between equals, a conflict that defined a generation.

Under the ambitious Khan Galdan Boshugtu, the Dzungars expanded aggressively, conquering neighboring territory and even invading Tibet, challenging the Qing Emperor’s authority. The Qing, under the shrewd and capable Kangxi Emperor, saw the Dzungars as an existential threat—a potential revival of the Mongol menace that had once conquered China.

The wars were brutal and epic in scale. In 1696, the Kangxi Emperor personally led a massive Qing army into the field against Galdan at the Battle of Jao Modo. Though the Qing ultimately triumphed due to superior logistics and numbers, the Dzungars inflicted heavy casualties and proved their mettle. For decades, the conflict raged on. The Dzungars were pushed back, only to roar back to life under new leaders like Tsewang Rabtan and Galdan Tseren. They raided deep into Mongolia, forcing the Qing to maintain a permanent, ruinously expensive military presence on their western frontier.

Annihilation: The End of an Era

The Dzungar Khanate’s golden age ended with the death of Galdan Tseren in 1745. His passing triggered a catastrophic succession crisis that descended into a bloody civil war. The once-unified state fractured as rival princes tore the Khanate apart, vying for the throne.

Observing this from Beijing was the Qianlong Emperor. Patient and determined, he saw his chance to solve the “Dzungar problem” once and for all. In 1755, as Dzungar factions appealed to him for aid against their rivals, he launched a massive invasion under the guise of restoring order.

The internally weakened Dzungars collapsed with shocking speed. But conquest was not enough for the Qianlong Emperor. Enraged by a final Dzungar rebellion, he made a chilling decision. In 1757, he issued orders that amounted to a policy of extermination.

What followed was one of the 18th century’s darkest episodes: the Dzungar Genocide. Qing armies, aided by a devastating smallpox epidemic, systematically hunted down and massacred the Dzungar people. Men were killed, and women and children were distributed as slaves. Historians estimate that of a population of perhaps 600,000, as many as 80% perished through a combination of war, disease, and outright slaughter. The Dzungar nation was effectively erased from existence.

Why the Dzungars Matter

The fall of the Dzungar Khanate was more than the end of a single empire. It was the definitive closing of a two-thousand-year chapter in world history: the age of the great nomadic conquests.

The Dzungars were the last, and arguably most sophisticated, attempt by a nomadic people to compete on equal terms with the burgeoning gunpowder empires. They adopted modern technology and statecraft, but ultimately, they could not overcome the vast demographic and industrial superiority of a centralized state like Qing China. The sheer scale, resources, and administrative power of the sedentary world had finally, irrevocably, outpaced the steppe.

Their annihilation left a power vacuum in Central Asia that was quickly filled by the Qing and an expanding Tsarist Russia. The era of the horse archer was over. The Dzungars were the final, brilliant, and tragic echo of a world that was vanishing forever, a testament to the last great riders of the steppe.