****

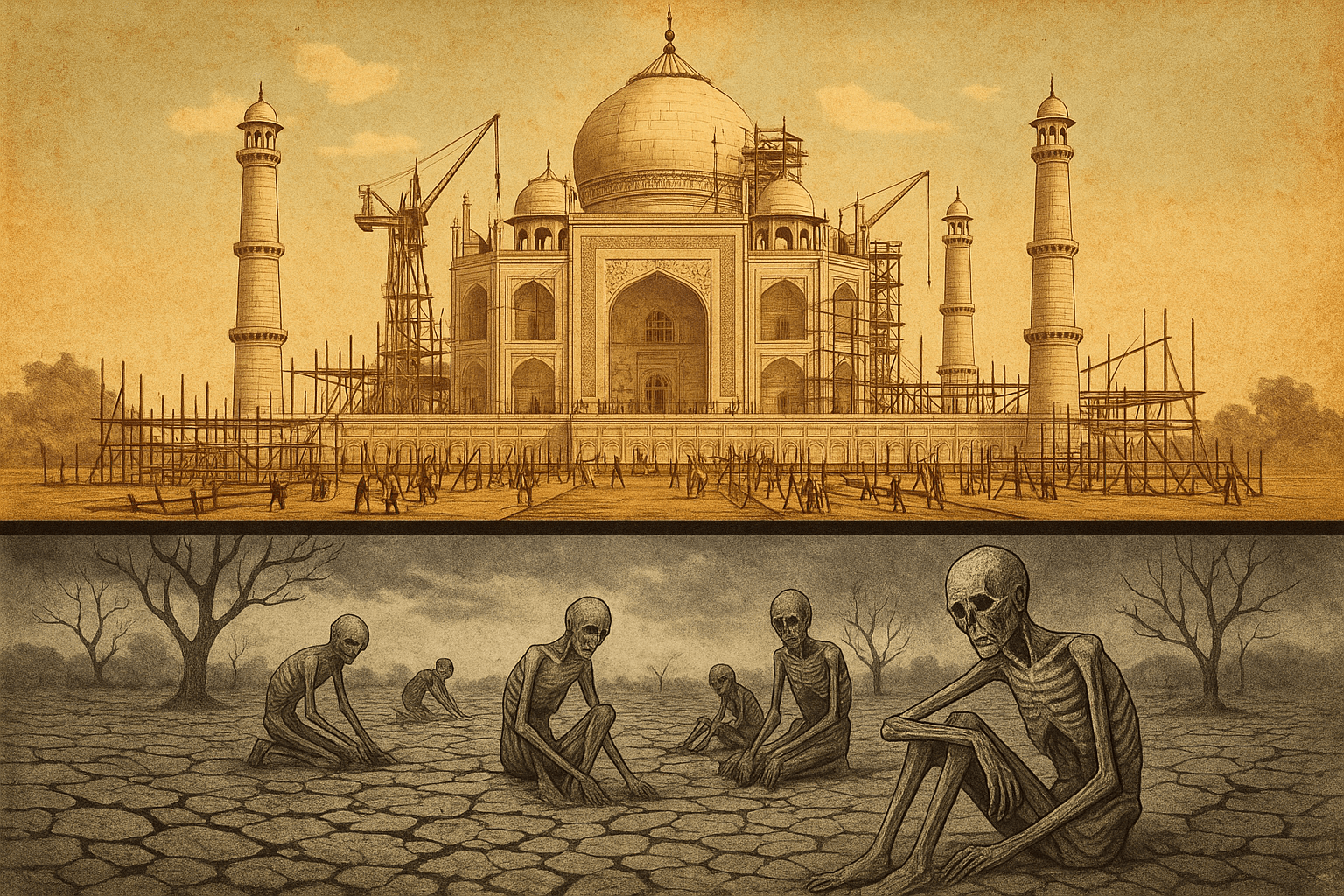

When we picture the reign of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, our minds conjure images of luminous marble, intricate artistry, and unparalleled opulence. We see the Taj Mahal, an eternal monument to love, standing as the ultimate symbol of his golden age. But behind this gleaming facade of imperial splendor lies a darker, far more harrowing story—one of mass starvation, death, and despair. This is the story of the Deccan Famine of 1630-32, a catastrophic event that unfolded in the very heartland of Shah Jahan’s ambitions.

A Perfect Storm: The Seeds of Calamity

The tragedy began not with the sword, but with the sky. For three consecutive years, starting in 1629, the vital monsoon rains failed across the Deccan plateau and the neighboring regions of Gujarat and Malwa. What was usually a life-giving deluge slowed to a sprinkle, and then ceased altogether. Rivers shrank to muddy trickles, reservoirs evaporated, and the land, once fertile, cracked and hardened under a relentless sun.

The immediate result was a complete and catastrophic crop failure. With no grain to harvest and no new crops to plant, food reserves dwindled and then vanished. The price of grain skyrocketed to twelve times its normal rate, pushing it far beyond the reach of the common person. The scarcity was all-encompassing; with no grass or fodder, livestock perished in droves. The foundation of agrarian life had crumbled, and a creeping, desperate hunger began to stalk the land.

The March of Armies, The March of Hunger

This natural disaster was hideously compounded by a man-made one: war. Shah Jahan, early in his reign, was determined to cement his authority over the Deccan Sultanates of Ahmadnagar, Golconda, and Bijapur. As the drought took hold, he was personally leading a massive Mughal army southward, with his main camp established at Burhanpur, right in the epicenter of the emerging crisis.

The presence of tens of thousands of soldiers and their followers acted as a devastating accelerant to the famine. Here’s how:

- Resource Depletion: The massive, non-productive army consumed whatever scarce grain, food, and water was available, competing directly with the starving local population.

- Destruction of Farmland: The constant movement of armies across the countryside trampled any struggling crops that had survived the drought, further destroying the food supply.

- Disruption of Trade: Military campaigns disrupted traditional trade routes, preventing grain from being imported into the famine-stricken regions from other parts of India.

- Pillaging and Hoarding: Desperate villagers who had managed to hide small reserves of grain were often plundered by soldiers. Officials and grain merchants, sensing opportunity, hoarded supplies to drive prices even higher.

In essence, the war effort not only drained the imperial treasury but also systematically dismantled the very mechanisms that might have provided relief, turning a severe crisis into an outright apocalypse.

An Empire of Splendor, A Land of Skeletons

The contrast between the imperial camp and the surrounding countryside was grotesque. While the nobility within Shah Jahan’s circle maintained a semblance of their luxurious lifestyle, the world outside was descending into a living hell. We have stark, eyewitness accounts from this period, most notably from the English merchant Peter Mundy and the official Mughal court historian, Abdul Hamid Lahori.

Peter Mundy, traveling through the region, was horrified by what he saw. He described the roads and streets as being littered with the dead and dying. His journal entries paint a chilling picture:

“The highways were strewn with corpses, and in various towns, half-dead and starving people were seen lying in the streets, unable to move. Those who could still walk were like veritable skeletons.”

Mundy documented scenes of unimaginable desperation. He wrote of parents selling their children into slavery for a handful of grain, of people eating boiled animal hides, and of a breakdown in all social order. Most disturbingly, he and Lahori both confirmed widespread reports of cannibalism. Lahori, in the official court chronicle Padshahnama, wrote that the desperation drove men to “devour their own kind,” with the flesh of a son being preferred to his love. Streets were so choked with the dead that passage was difficult.

It was in the midst of this horror, in the city of Burhanpur in 1631, that Shah Jahan’s beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal, died from complications of childbirth. Her death, which would inspire the creation of the Taj Mahal, occurred in the very heart of the famine zone. The sorrow of an emperor stood in stark, silent contrast to the agony of millions.

The Imperial Response: Too Little, Too Late?

To his credit, Shah Jahan did not completely ignore the suffering. Faced with a catastrophe of this magnitude, he did initiate some relief measures. He ordered the establishment of langars (public soup kitchens) in Burhanpur, Ahmedabad, and Surat to distribute free food. He also approved tax remissions, waiving a significant portion of the annual revenue demand on the afflicted provinces.

However, these efforts were a drop in a vast, desolate ocean. The relief was disorganized and woefully inadequate to combat the scale of the starvation. More critically, the emperor did not halt his military campaigns. The very engine of war that was exacerbating the famine continued to churn, consuming resources that could have been diverted to saving lives. The aid provided was a bandage on a wound that was simultaneously being deepened by the emperor’s own policies.

The Forgotten Legacy

By the time the rains finally returned in late 1632, the damage was absolute. Modern historians estimate that the famine claimed the lives of at least seven million people. Entire districts and villages were depopulated, with agriculture and local industries collapsing completely. It would take decades for the Deccan to recover.

Today, this immense human tragedy is largely a footnote in the popular telling of Shah Jahan’s reign. We remember the builder of the Taj Mahal, the patron of the arts, the ruler of a dazzling empire. We have largely forgotten the emperor whose military ambitions helped fuel one of the most horrific famines in India’s history. The story of the Deccan Famine is a powerful reminder that history is often written by the monuments we leave behind, but its true lessons are found in the suffering we choose to forget.

**