Imagine Europe in 3000 BCE. For millennia, the continent had been the domain of the first farmers, people who had migrated from Anatolia, bringing agriculture, settled villages, and monumental stone structures like Stonehenge and the tombs of Newgrange. Theirs was a world built on communal effort and a deep connection to the land they tilled. Then, in the archaeological blink of an eye, everything changed. A new cultural phenomenon swept across the northern plains, from the Rhine to the Volga, bringing with it a different way of life, a different way of death, and, as we now know, different people.

This was the dawn of the Corded Ware Culture, a transformation so profound that it redrew the genetic and linguistic map of Europe forever.

A Signature in Clay and Stone

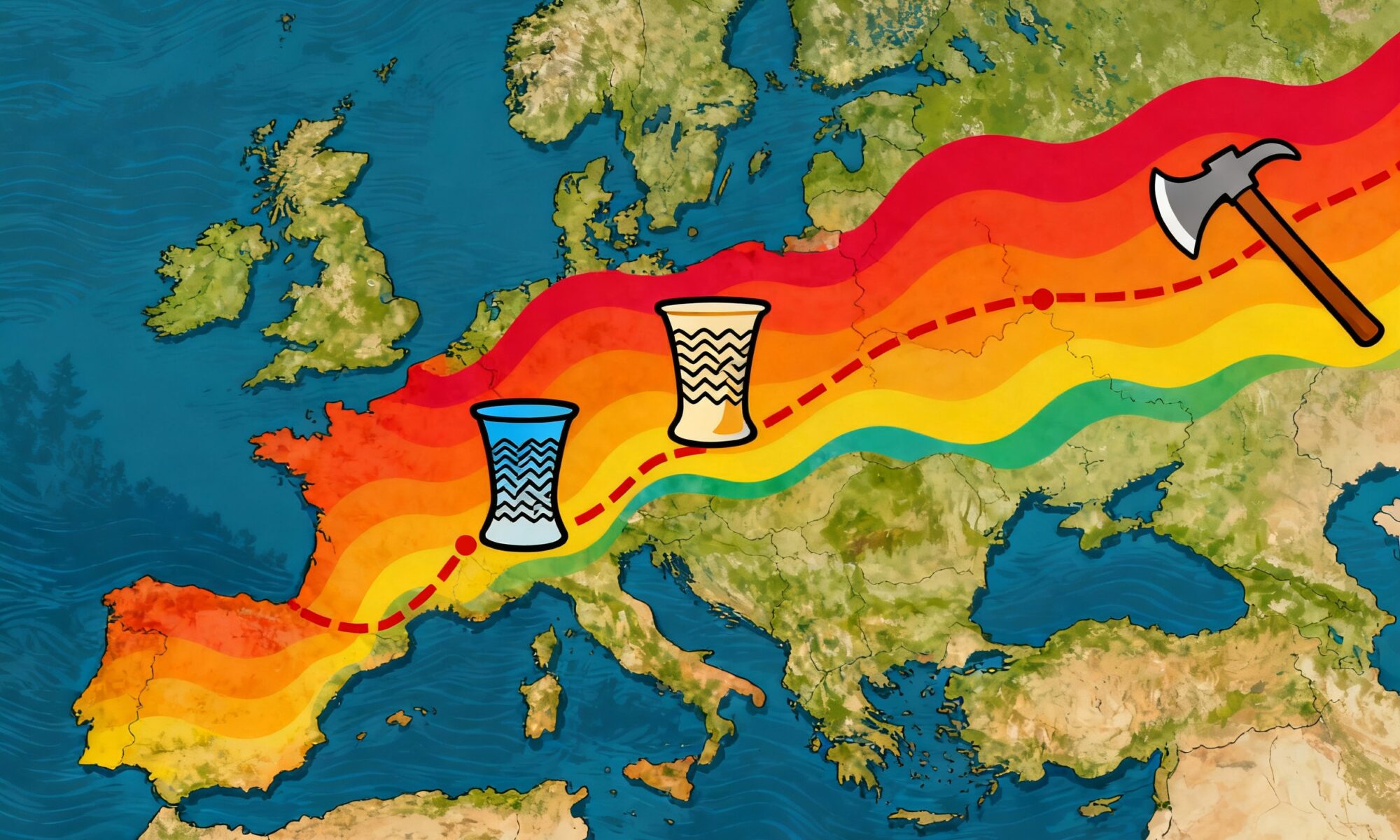

Archaeologists name cultures after their most distinctive artifacts, and the Corded Ware is no exception. Its calling card is a simple yet elegant style of pottery: beakers, amphorae, and bowls decorated by pressing a twisted cord into the wet clay before firing. This technique, found across thousands of miles, created a unified cultural “horizon” that signaled a shared identity.

But their signature wasn’t just left in clay. The Corded Ware people are also known for another iconic artifact: the stone battle-axe. Finely polished, drilled with a perfect shaft-hole, and shaped like a boat, these were not just practical tools. They were status symbols, buried almost exclusively with men, representing power, prestige, and a martial ethos that seems to stand in stark contrast to the world of the Neolithic farmers they encountered.

This new worldview is most powerfully expressed in their burial practices. The Neolithic peoples of Atlantic Europe often built massive, communal tombs—megaliths where the bones of generations were intermingled. The Corded Ware people introduced a radical new concept: the single grave. Their dead were buried individually, often under a small earthen mound (a barrow or kurgan), in a flexed or “fetal” position. There was a strict formula:

- Men: Buried on their right side, heads to the west, facing south.

- Women: Buried on their left side, heads to the east, also facing south.

This focus on the individual, with gender-specific rites and grave goods like the battle-axe for men and decorative items for women, points to a society structured around the nuclear family and individual identity, a significant departure from the communal focus of their predecessors.

Whispers from the Steppe: The Yamnaya Connection

For decades, scholars debated the origin of the Corded Ware phenomenon. Was it an idea that spread, a new fashion adopted by local peoples? Or was it the result of a mass migration? The answer, it turns out, lay far to the east, on the vast, grassy plains north of the Black and Caspian Seas.

This was the homeland of the Yamnaya culture, a society of nomadic pastoralists who had mastered horse riding and developed wheeled wagons. Living a mobile life centered on vast herds of cattle and sheep, they buried their elite in deep pits under towering kurgans. Around 3000 BCE, for reasons still debated—perhaps climate change, population pressure, or technological advantage—the Yamnaya exploded out of their steppe homeland in one of the most significant migrations in human history.

One major branch pushed west, and as they moved into the forests of Northern and Central Europe, their culture adapted. They became the Corded Ware people. The mobile, pastoralist lifestyle, the kurgans, the focus on the individual—all these elements have their roots in the Yamnaya world. The Corded Ware culture was not just an idea; it was the western vanguard of a massive steppe expansion.

A Revolution Written in DNA

The definitive proof of this migration came not from pottery or axes, but from the bones of the dead themselves. The field of archaeogenetics, the study of ancient DNA (aDNA), has completely revolutionized our understanding of prehistory. When scientists began sequencing the genomes of Corded Ware skeletons, they made a startling discovery.

These individuals carried a massive amount of a new genetic signature, what scientists call “Steppe ancestry.” In many regions, the DNA of Corded Ware people was up to 75% derived from the Yamnaya. This was not a slow blending of populations; it was a demographic turnover on a continental scale. The genetic profiles of the earlier Neolithic farmers, who had dominated Europe for 4,000 years, largely vanished from the record, replaced by this new influx from the east.

The story told by the Y-chromosome (passed down from father to son) is even more dramatic. A specific lineage, haplogroup R1a, which was common among the Yamnaya, becomes utterly dominant in Corded Ware populations. This suggests the migration was led by men, who then started families with local women, fundamentally and permanently replacing the previous male lineages.

The Echo of a Lost Tongue: Spreading Indo-European Languages

This huge movement of people inevitably carried with it another powerful, though invisible, element: language. Today, hundreds of languages, from Hindi and Persian in the east to English, German, Spanish, and Russian in the west, belong to a single family: Indo-European. Linguists have long known they all descended from a common ancestor, a “Proto-Indo-European” (PIE) tongue spoken thousands of years ago. But where, and by whom?

The “Steppe Hypothesis”, now overwhelmingly supported by the genetic evidence, provides the answer. The Yamnaya and their relatives were the speakers of late PIE. As they migrated, they brought their language with them. The Corded Ware expansion was the vehicle that carried Indo-European languages into the heart of Northern Europe. Over the centuries, the language spoken by these steppe migrants would evolve and diversify, eventually becoming the ancestors of the Germanic, Slavic, and Baltic language branches spoken there today.

The Corded Ware expansion was, therefore, not just a genetic revolution but a linguistic one. When you speak English or German, you are speaking a language whose distant origins lie on the Pontic-Caspian steppe, carried into Europe by men with battle-axes and a new way of honoring their dead.

A New Europe is Forged

The arrival of the Corded Ware people marks the beginning of the end of Old Neolithic Europe and the start of something new: the Bronze Age. They brought a more mobile, pastoralist-focused economy, a social structure centered on the individual warrior and the nuclear family, and a new genetic and linguistic heritage. While the process was likely complex and varied from region to region—involving conflict, assimilation, and social collapse—the outcome was decisive. Within a few centuries, the genetic and cultural landscape of Northern Europe had been transformed. The foundations of modern European populations and languages were laid, not by quiet farmers in settled villages, but by a dynamic and expansive culture that swept out of the east, leaving its indelible signature in cord-marked clay, stone axes, and the very DNA of the continent.