When we picture the Golden Age of Piracy, our minds often drift to the sun-drenched, rum-soaked islands of the Caribbean. We imagine Jack Sparrow-esque figures clashing with the Royal Navy amidst turquoise waters. But for a generation of the most successful and ruthless pirates in history, the real fortune wasn’t in the Atlantic. It was a treacherous, year-long voyage away in the Indian Ocean, and the key to it all was a remote, lawless island off the coast of Africa: Madagascar.

This daring venture was known as the Pirate Round. Beginning in the 1690s, crews would sail from ports in the Americas or the Caribbean, round the Cape of Good Hope, and lie in wait for the richest prizes on the planet. Their destination wasn’t just a raiding ground; it was a new home, a semi-permanent base that became the stuff of legend.

Why Madagascar? The Perfect Pirate Paradise

For a pirate captain looking to strike it rich, Madagascar was more than an island; it was a strategic masterpiece. Its appeal was a potent cocktail of geography, politics, and natural abundance.

- Strategic Location: The island sat astride the vital maritime trade routes of the Indian Ocean. From its northern shores, pirates could easily intercept treasure-laden ships sailing from Mughal India, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea. These vessels, particularly the pilgrim fleets heading to Mecca, were often lightly armed and filled with gold, silver, and precious goods, making them far juicier targets than the Spanish galleons of the Caribbean.

- A Lawless Land: Unlike the increasingly policed Caribbean, Madagascar had no dominant European power. There were no governors to hang pirates, no naval squadrons to hunt them down. It was a blank spot on the map of colonial authority, offering a freedom that was impossible to find elsewhere.

- A Natural Haven: The island was a lush, self-sustaining paradise. Pirates found safe anchorages in its hidden bays, abundant fresh water, a seemingly endless supply of fruit and cattle, and ample timber to careen and repair their battered ships after the long voyage. It was a place to rest, re-arm, and plan the next raid in relative safety.

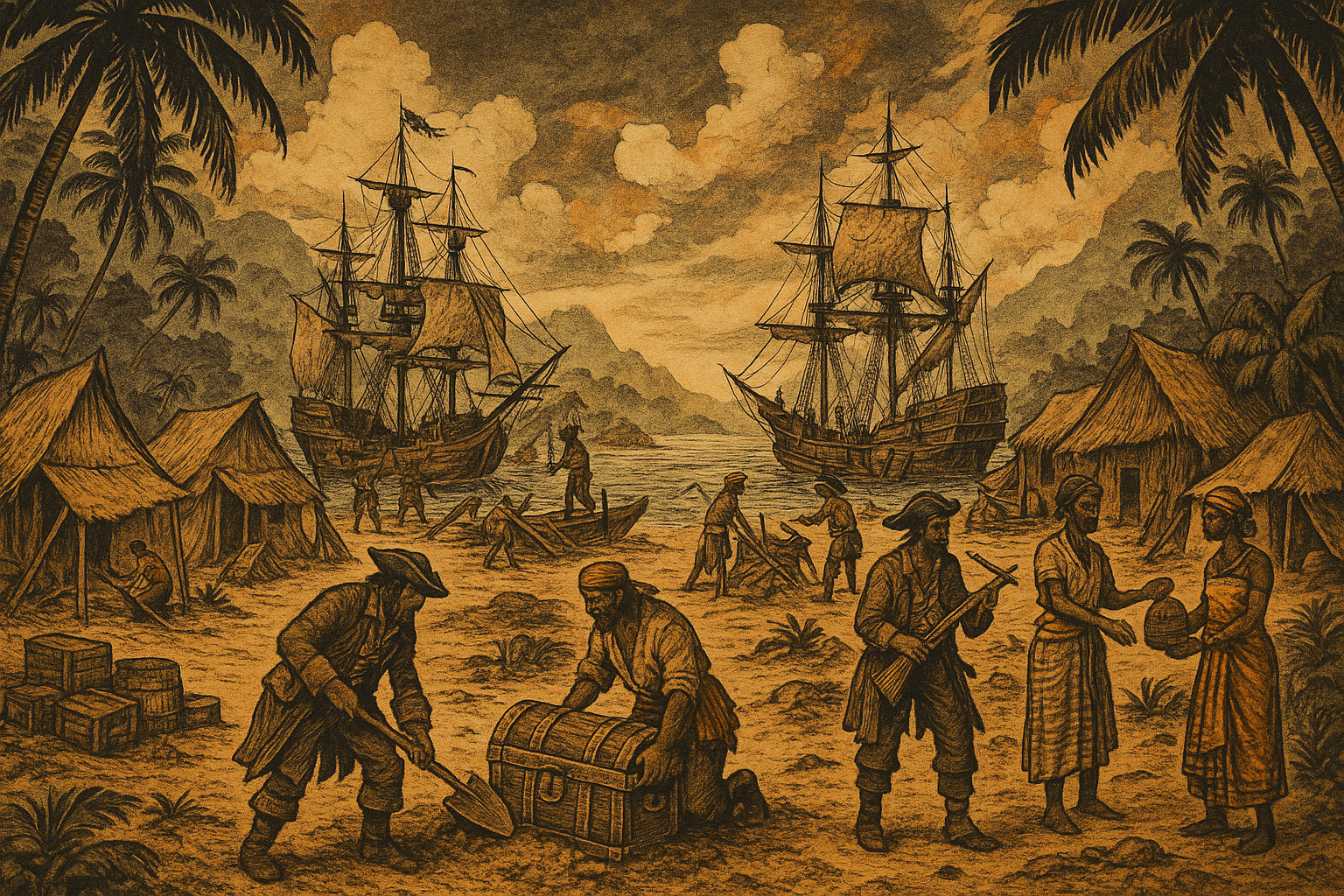

The relationship with the indigenous Malagasy people was complex and crucial. Pirates traded liquor, firearms, and stolen goods for food, supplies, and assistance. Some pirates, far from home and with no intention of returning, integrated into local society, marrying Malagasy women and even becoming powerful figures in local tribal politics. This created unique, hybrid communities where pirate culture blended with local tradition.

The Notorious Havens: Île Sainte-Marie and Libertalia

Within Madagascar, certain locations became synonymous with piracy. The most famous of these was Île Sainte-Marie (St. Mary’s Island), a small island off the northeast coast. Its long, narrow bay provided a perfect, naturally protected harbor. By the late 1690s, it had grown into a bustling, if ramshackle, pirate metropolis.

This was the base of operations for legendary figures like Thomas Tew, Henry Every, and later, William Kidd and Olivier Levasseur. Imagine a town built of salvaged ship parts and palm fronds, populated by hundreds of pirates from around the world. Here they would careen their ships, divide their loot, trade with unscrupulous merchants, and carouse with the vast fortunes they had plundered. The pirate cemetery on Île Sainte-Marie, with its skull-and-crossbones-carved headstones, remains a haunting testament to this era.

While Sainte-Marie was undeniably real, Madagascar was also the setting for a more utopian, and likely mythical, pirate settlement: Libertalia. Chronicled in Captain Charles Johnson’s 1724 book A General History of the Pyrates, Libertalia was supposedly a free colony founded by the radical pirate Captain Misson. In this anarchist paradise, all men were free and equal, property was held in common, and a democratic government ruled. Slavery was abolished, and the motto was “For God and Liberty.”

Most historians today believe Libertalia was a fictional creation, a political allegory designed to critique the oppressive monarchies and social hierarchies of Europe. Yet, the legend’s power lies in how it reflected the real aspirations of many pirates. Life on a pirate ship, with its democratically elected captains and shared articles of agreement, was a radical departure from the brutal tyranny of naval and merchant vessel life. Libertalia may not have existed, but the desire for such a free society was very real in the minds of the men who called Madagascar home.

The Kings of the Round

The Pirate Round was defined by the larger-than-life characters who dared to undertake it. The man who truly ignited the frenzy was Henry Every, also known as “Long Ben.” In 1695, his capture of the Mughal treasure ship Ganj-i-Sawai netted one of the largest hauls in pirate history, worth an estimated £600,000 (over $100 million today). The audacious act made Every the most wanted man on earth and inspired a flood of pirates to follow his route to the Indian Ocean.

One of the pioneers was Thomas Tew, whose initial success on the Round provided the proof of concept. He established himself at Île Sainte-Marie, demonstrating how a permanent base could sustain long-term pirate operations.

The story of Captain William Kidd is perhaps the most tragic. Dispatched from England as a privateer specifically to hunt down pirates like Tew, Kidd found himself entangled in the murky world he was meant to destroy. He used the pirate bases on Madagascar, and his actions ultimately led to his branding as a pirate, his arrest, and his execution in London. His tale served as a cautionary warning about the thin line between law and lawlessness on the Pirate Round.

The End of an Era

The golden age of the Madagascar pirate bases could not last. The spectacular success of Henry Every had an unintended consequence: it infuriated the powerful Mughal Empire and the British East India Company. In response, the Royal Navy began a concerted effort to police the Indian Ocean.

Simultaneously, the Crown offered royal pardons, tempting many pirates to give up the life and return to “civilization.” Some pirates simply retired, settling down and assimilating into Malagasy society. By the 1720s, with increased naval patrols, the offer of pardons, and a new generation of pirates focusing on a declining Caribbean, the Pirate Round came to an end. Madagascar’s time as the world’s foremost pirate sanctuary was over.

The legacy of the Madagascar bases, however, endures. They were the lynchpin of the most profitable period of piracy the world has ever known. Part historical reality, part revolutionary myth, these havens represent a unique chapter in maritime history—a time when, for a fleeting moment, a handful of outlaws on a remote island could challenge empires and live by a code all their own.