A Royal Mailbag in the Sand

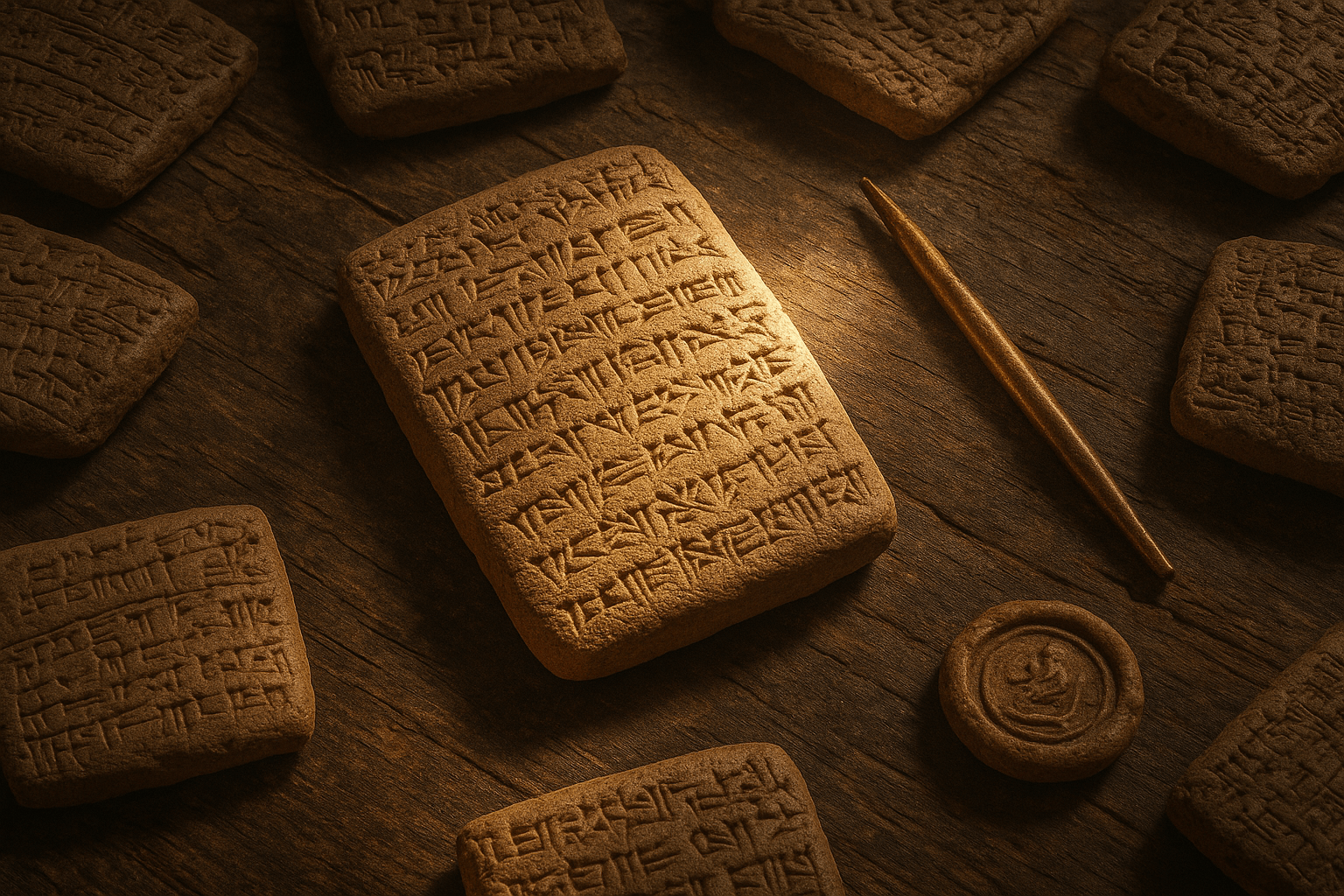

The letters were discovered at the ruins of Akhetaten (modern Amarna), the short-lived capital city built by the “heretic” Pharaoh Akhenaten. Dating primarily to the reigns of his father, Amenhotep III, and Akhenaten himself (c. 1353-1336 BCE), this archive was Egypt’s equivalent of a state department’s filing cabinet. What makes them so extraordinary is the language they were written in: Akkadian cuneiform. Not Egyptian hieroglyphs, but the Mesopotamian script that served as the international language of diplomacy for the entire ancient Near East. It was the English of its day, a common tongue that allowed kings from the Nile to the Euphrates to communicate directly.

This collection wasn’t a one-sided affair. It contains letters sent to the Pharaoh from other great rulers, as well as copies of tablets sent from Egypt. Even more numerous are the desperate pleas from vassal kings in Canaan and Syria, territories under Egyptian control. Together, they paint a vivid picture of a deeply interconnected world, bound by a fragile web of treaties, trade, and family ties.

The ‘Great Powers Club’

At the top of the international hierarchy was an exclusive group of rulers who addressed each other as “Brother.” This ‘Great Powers Club’ recognized one another as equals on the world stage. The key members were:

- Egypt: The superpower, seen as an ancient and fabulously wealthy kingdom.

- Babylonia (Karanduniash): Ruled by the Kassite dynasty, an old and prestigious kingdom.

- Mitanni (Hanigalbat): A powerful Hurrian kingdom in northern Syria and Mesopotamia.

- Hatti: The Hittite kingdom in Anatolia (modern Turkey), a rising and ambitious military power.

- Assyria: An emerging power in northern Mesopotamia, eager for a seat at the main table.

The letters between these “Brothers” are an exercise in careful diplomatic language. They begin with effusive greetings, wishing health upon the king, his household, his wives, his children, his horses, and his chariots. But beneath the flowery pleasantries lay hard-nosed negotiations and strategic calculations.

The Currency of Diplomacy: Gold, Goddesses, and Daughters

What did these great kings write to each other about? Their correspondence revolved around the essential elements that held their world together: the exchange of luxury gifts, strategic dynastic marriages, and the maintenance of prestige.

The Lust for Gold

Egypt’s greatest asset was its perceived inexhaustible supply of gold, sourced from the mines of Nubia. To the other great kings, Pharaoh was the ultimate source of wealth, and their letters are filled with incessant demands for it. King Tushratta of Mitanni famously wrote to Amenhotep III, reminding him that in Egypt, “gold is as plentiful as dust.”

This wasn’t simple greed. In the Late Bronze Age, a king’s power was demonstrated by his ability to distribute lavish gifts. Gold was the ultimate status symbol, the raw material of royal power. When a Babylonian king complains that the gold he received from Pharaoh was not pure, it was more than a financial complaint; it was an insult to his honor and a suggestion that the Pharaoh was not treating him as an equal.

Royal Marriages

A primary way to seal an alliance was through marriage. Foreign kings were eager to send their daughters to join the Pharaoh’s harem, a move that cemented their “brotherly” bond with the Egyptian court. Tushratta of Mitanni sent his daughter, Tadukhipa, to be a wife for Pharaoh. But this traffic in princesses was a one-way street. When the king of Babylon, Burna-Buriash II, asks for an Egyptian princess for himself, he is flatly denied. The Egyptian response is blunt: “From time immemorial no daughter of the king of Egypt is given to anyone.” Pharaohs would happily receive foreign princesses but would never send their own daughters abroad, a clear assertion of Egypt’s superior status.

Voices from the Fringes: Trouble on the Periphery

While the Great Kings negotiated as “Brothers”, a significant portion of the Amarna archive consists of letters from a different class of ruler: the vassal kings of city-states in the Levant (modern-day Syria, Lebanon, and Israel). These letters are far from the polite exchanges of the superpowers. They are frantic, desperate, and often accusatory.

Rulers like Rib-Hadda of Byblos and Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem were sworn to the Pharaoh, but their territories were rife with conflict. They write endlessly of attacks from neighboring rivals, encroachment by the Hittites, and the plundering of a mysterious group known as the ‘Apiru (or Habiru). Their letters are a chorus of pleas for Egyptian troops and resources.

“May the king, my lord, know that all the lands are at war… I am afraid. Send troops!”

This is the typical tone. These vassals accuse each other of treachery and complain that the Pharaoh is ignoring their plight. Whether Akhenaten was truly neglectful, distracted by his religious revolution at home, or whether this chaos was simply the normal state of affairs in the Egyptian empire is a matter of debate. What is clear is that maintaining control over these distant territories required constant attention—attention that may have been waning.

A World on the Brink

The Amarna Letters don’t just show us a functioning diplomatic system; they also capture the cracks beginning to appear. The confident rise of the Hittite King Suppiluliuma I can be felt in the background, as he masterfully undermines Egyptian influence in Syria. The cheeky letter from Ashur-uballit I of Assyria, who asserts his right to be called a “Great King” on par with Pharaoh, signals a shift in the balance of power.

Ultimately, the world documented in the Amarna Letters was not destined to last. Within 150 years, a series of cataclysms now known as the Late Bronze Age Collapse would bring this interconnected world crashing down. The Hittite and Mitanni empires would vanish, Egypt would be weakened and diminished, and the great international network of trade and diplomacy would shatter. The Amarna Letters, therefore, are more than just a diplomatic snapshot. They are a precious, frozen moment in time, a last glimpse of an ancient globalized world before the lights went out.