The Sacred Breath of the Sea

Before it could become a message, wampum first had to be created, a laborious and spiritual process. The beads themselves are carved from specific seashells found along the Atlantic coast. The white beads, representing peace, purity, and light, come from the inner spiral of the channeled whelk shell. The more valuable and symbolically potent purple beads, representing serious or political matters, are painstakingly ground from the thickest part of the quahog clam shell.

Imagine the skill required, before the introduction of European metal tools, to drill a fine hole through these brittle shells. Each bead was a small work of art, polished by hand until smooth. Their value came not from a standardized monetary assignment, but from the immense effort of their creation and the sacred power imbued in them by their origin—the ocean, a place of great spiritual importance. The beads were seen as a gift from the Creator, and to work with them was to engage in a sacred act.

A Living Library of Belts and Strings

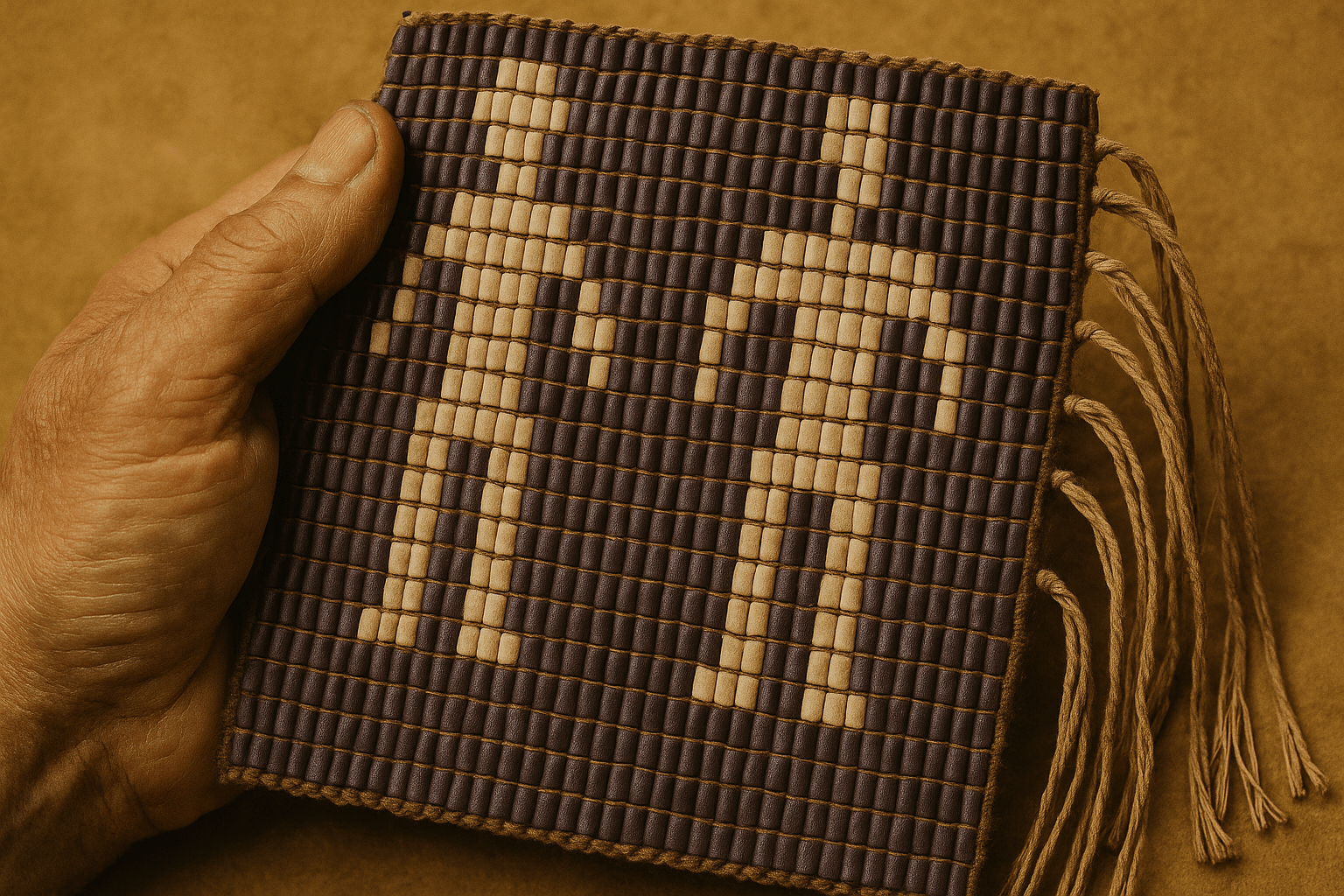

The Haudenosaunee did not have a written language in the European sense. Instead, they developed a sophisticated system of mnemonic record-keeping using wampum. Strings of wampum could be used for smaller messages, as invitations to councils, or as credentials for a messenger. But the most significant records were woven into intricate belts.

These belts were not an alphabet. The symbols, colors, and patterns woven into them served as memory aids, enabling a designated “Wampum Keeper” to recite the associated history, law, or treaty. The Wampum Keeper was a highly trained individual with a prodigious memory, tasked with preserving and interpreting the belts for their community. When a belt was presented at a council, the Keeper would hold it, reading its physical texture and visual design to recall the exact words and spirit of the agreement or story it represented. The collection of a nation’s belts was its archive, its constitution, and its library, holding the collected wisdom of generations.

The Hiawatha Belt: A Nation’s Blueprint

Perhaps the most important wampum belt in existence is the Hiawatha Belt. This belt is the foundational document of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, memorializing its creation centuries before European contact. Made of purple shells, the belt features five white symbols.

- At the center is a symbol of a Great White Pine, the Tree of Peace, representing the Onondaga Nation, the capital of the Confederacy and the Keepers of the Council Fire.

- To its sides are four white squares, representing the other four original nations: the Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca.

- These five figures are connected by a white band, the Path of Peace, which extends off both ends of the belt, inviting other nations to take shelter under the Great Tree and accept the Great Law of Peace.

This belt is not just a historical artifact; it is a political map and a constitution. It codifies the unity of the five nations, their pledge to live in peace and support one another, and their open invitation for others to join them. Holding this belt is holding the birth of one of the world’s oldest participatory democracies.

Binding Words: Wampum in Diplomacy

When Europeans arrived, they brought with them a tradition of written treaties on paper or parchment. For the Haudenosaunee, this was a fragile and untrustworthy medium. A document could be forged, misinterpreted, or easily destroyed. A promise, to be sacred and binding, had to be made tangible. This is where wampum played its most critical diplomatic role.

Exchanging wampum belts sanctified a treaty. The act of presenting and accepting a belt was how both sides pledged their honor. The belt itself became the physical embodiment of the agreement. As long as the belt was preserved, the agreement was in force. To break the treaty was to desecrate the physical record and the sacred shells it was made from—an act of profound dishonor.

The Two Row Wampum: A Treaty of Mutual Respect

A prime example is the Two Row Wampum Belt, or Kaswentha, which records the first agreement between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch, dating to 1613. The design is simple but its meaning is immense. The belt consists of three white rows separated by two purple rows.

The Haudenosaunee explanation is powerful: The white background represents a river of life. On this river, two vessels travel side-by-side. One is the Haudenosaunee canoe, containing their laws, culture, and way of life. The other is the European ship, with their laws, religion, and customs. The two vessels are to travel down the river together, in parallel, never interfering with one another. The three white rows symbolize the principles that keep them separate and in peace: friendship, mutual respect, and peace. The Kaswentha is a treaty of non-interference and co-existence, a sophisticated political concept of sovereignty that is as relevant today as it was 400 years ago.

The Corruption of a Sacred Tradition

The colonial misunderstanding of wampum had devastating consequences. Seeing its value in Native society, Dutch and English colonists sought to control its production. They established “wampum mills” in places like modern-day New Jersey and Long Island, using metal drills to mass-produce beads far more efficiently than by hand. They then began using it as a colonial currency, fixing exchange rates for trade with both Native nations and other colonists.

This monetization flooded the Northeast with wampum, devaluing it and fundamentally corrupting its purpose. It commodified a sacred object, undermining the very social and political structures it was meant to uphold. The term “money” stuck, and for centuries, the true meaning of wampum was buried under this commercial interpretation.

A Living Symbol of Resilience

Wampum was never just money. It was a language of diplomacy, a keeper of laws, and a vessel for history. The belts are living documents, imbued with the collective memory and honor of nations. To touch a historic wampum belt is to feel the weight of a promise made centuries ago.

Today, the Haudenosaunee and other Native nations continue to work to repatriate their historic belts from museums and private collections. These are not relics to be displayed behind glass, but vital components of their ongoing governance and ceremonies. The tradition of wampum is not dead; it is a powerful symbol of cultural resilience and the enduring sovereignty of the people who created it.