The discovery was serendipitous. The diver, Mehmet Çakır, reported seeing “metal biscuits with ears” on the seabed. Those “biscuits” were in fact copper ingots, the first clue to one of the richest and most significant underwater archaeological finds in history. Over the next decade, a painstaking excavation led by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology revealed a ship frozen in time, its cargo a breathtaking testament to a vibrant, interconnected world that existed more than a millennium before the Roman Empire.

A Floating Marketplace of the Ancient World

Calling the Uluburun’s cargo a “king’s ransom” is no exaggeration. It was a collection of raw materials, luxury goods, and everyday items that originated from at least ten different cultures. The ship was not just carrying tribute for a king; it was a commercial vessel, a floating marketplace conducting business across the Mediterranean. The sheer diversity of its contents is staggering.

The Raw Materials of an Empire

The bulk of the weight on board came from raw materials, the essential ingredients for the craftsmen and workshops of the Bronze Age palaces.

- Copper Ingots: The most significant part of the cargo was over 350 “oxhide” ingots—so-named for their distinctive shape with four protruding handles. Weighing around 10 tons in total, this copper was traced back to the mines of Cyprus, the main copper source of the era.

- Tin Ingots: To make bronze, you need copper and tin. The ship also carried roughly a ton of tin ingots, a far rarer commodity. Its source is believed to be the distant mountains of what is now Afghanistan or Tajikistan, highlighting an incredibly long and complex supply chain.

- Glass Ingots: Archaeologists recovered about 175 disc-shaped ingots of raw glass in vibrant cobalt blue, turquoise, and even a unique lavender color. These are the earliest intact glass ingots ever found, likely originating from Canaan (modern-day Syria/Lebanon) or Egypt.

- Exotic Resources: The ship was also carrying logs of African Blackwood (ebony) from Nubia, south of Egypt; whole elephant tusks and hippopotamus teeth for ivory carving; and over a ton of terebinth resin, an aromatic substance used in perfume and incense, stored inside Canaanite jars.

Finished Goods and Personal Treasures

Mixed in with the raw materials was an incredible assortment of manufactured goods, personal items, and curiosities that tell a human story.

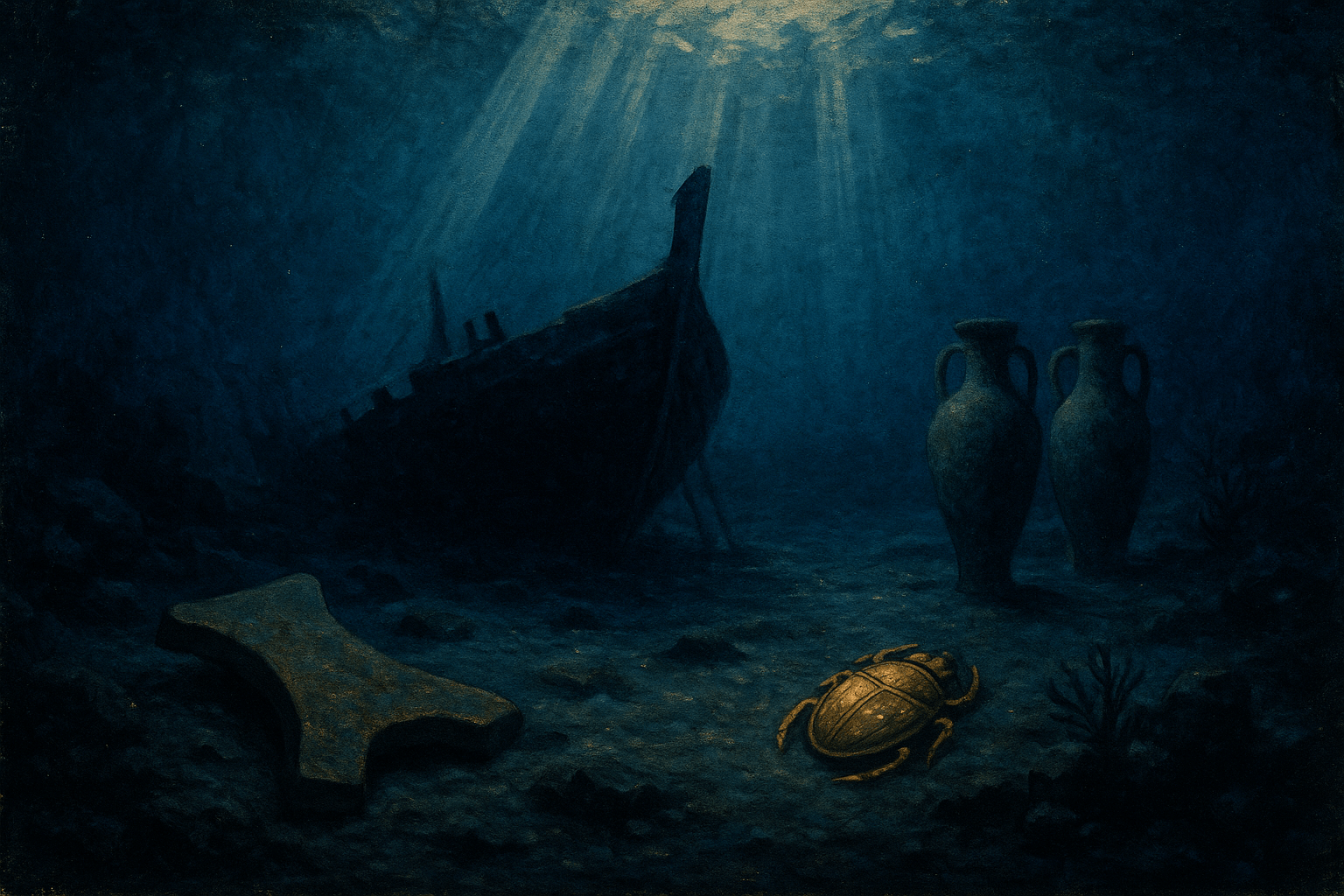

- Pottery: The ship’s hold contained a “pantry” of beautiful ceramics. There were large Canaanite amphorae (storage jars) filled with goods like olives and pistachios, elegant Mycenaean Greek stirrup jars likely used for fine oils, and Cypriot-made flasks and bowls.

- Jewelry and Adornments: Among the most captivating finds was a collection of Canaanite gold jewelry, including pendants and a beautiful medallion featuring a goddess. Most famously, a solid gold scarab bearing the name of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti was discovered, helping to date the shipwreck.

- Weapons and Tools: The international character of the voyage was evident in its arsenal. There were swords of Canaanite, Mycenaean, and even Italian design. Bronze spearheads, daggers, axes, and a variety of tools were also part of the cargo.

- A World of Weights and Measures: A meticulously organized set of pan-balance weights in various shapes (animals, geometric forms) was found, a clear indicator of merchants conducting precise business on board.

- The World’s Oldest “Book”: One of the most unique artifacts was a small, hinged wooden diptych with recessed ivory surfaces. These surfaces would have held beeswax for writing, making it a precursor to the modern book and one of the oldest examples ever found.

Unraveling the Mystery: Who Was Onboard?

The ship itself, built of Lebanese cedar using advanced mortise-and-tenon joints, was likely of Canaanite or Cypriot origin. But who was sailing it? The artifacts suggest a multinational crew. The main merchants were probably Canaanite, but the discovery of two sets of Mycenaean personal effects—including bronze razors, tableware, and glass relief beads—suggests there were at least two high-status Greeks on board, perhaps as envoys or merchants overseeing their own interests.

The ship’s final voyage likely began on the Levantine coast and followed a counter-clockwise route across the Mediterranean. After stopping in Cyprus and possibly Crete, it was heading west along the southern coast of Anatolia (Turkey) when disaster struck. Perhaps caught in a sudden storm, the ship was driven onto the rocky promontory of Uluburun and sank, its precious cargo spilling onto a steep underwater slope where it would lie undisturbed for over 3,300 years.

Why the Uluburun Wreck Changed Everything

Before the discovery of the Uluburun, our picture of Late Bronze Age trade was much simpler. It was thought to be dominated by “gift exchanges” between great kings—formal, state-controlled shipments of tribute and diplomatic presents. The Uluburun shipwreck blew that theory out of the water.

This single vessel proved the existence of a sophisticated, complex, and largely private commercial network. It was a world of entrepreneurs and international merchants, a system of supply and demand that we would today call globalization. The cargo wasn’t just a royal shipment; it was a mixed consignment. The copper and tin were likely headed for a major Aegean center—perhaps a Mycenaean palace—to be forged into weapons and tools. The glass, ivory, and resin were luxury goods for the elite. The pottery, food, and personal items were part of the fabric of daily life and trade at sea.

The Uluburun reveals a Late Bronze Age Mediterranean that was a buzzing hub of interaction. A Canaanite ship, carrying goods from Africa, the Near East, and Central Asia, along with Greek passengers, was wrecked off the coast of Anatolia while likely heading to an Aegean port. It is a stunning snapshot of a deeply interconnected world, bound not just by kings and politics, but by the universal human drivers of commerce and craft.