These ruins, scattered across modern-day Peru, are more than just archaeological sites; they are a blueprint of power. They reveal a society obsessed with order, control, and state-sponsored efficiency—a marvel of pre-Columbian urban design that tells the story of the Andes’ first great empire.

Who Were the Wari?

Flourishing from their capital, Huari, in the central highlands, the Wari were a military and administrative powerhouse. Through a combination of conquest, diplomacy, and cultural influence, they forged a complex state that spanned over 1,500 kilometers, incorporating a diverse array of local peoples. They were contemporaries of the Tiwanaku state to the south (in modern-day Bolivia), and their relationship was a complex mix of rivalry, trade, and mutual influence.

What set the Wari apart was their approach to imperial administration. They didn’t just conquer and extract tribute; they fundamentally reorganized the lands they controlled. At the heart of this strategy was the construction of massive, pre-planned administrative centers, built from scratch to project imperial authority into the provinces.

The Blueprint of a Centralized State

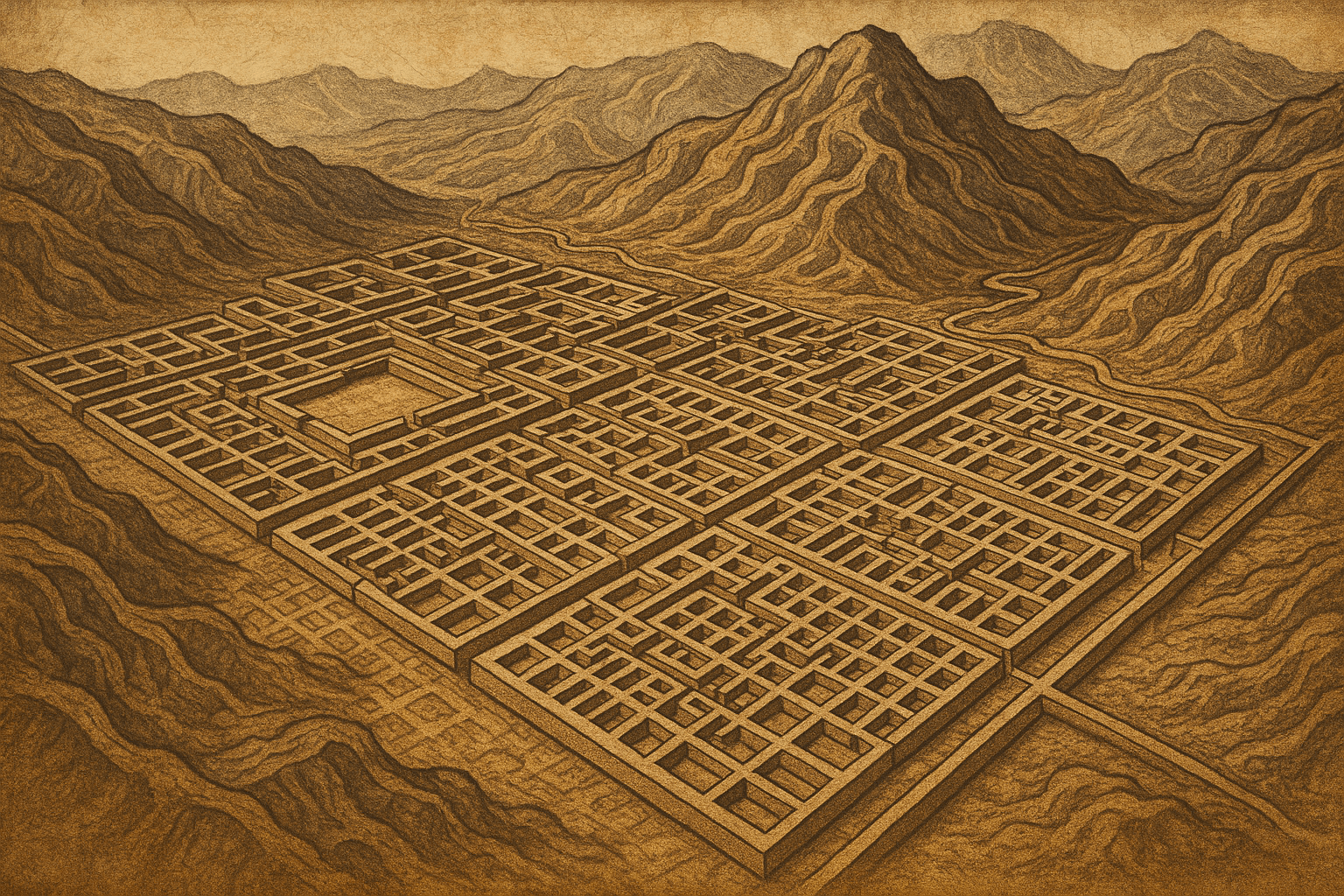

Unlike cities that grow organically over centuries, Wari provincial centers look as though they were dropped onto the landscape from a single architectural drawing. Their defining feature is a strict orthogonal grid, with straight streets intersecting at perfect right angles. This rigid layout is a hallmark of immense centralized power.

Consider what it takes to build such a city:

- Advanced Planning: Surveyors and architects had to map out the entire city before a single stone was laid.

- Massive Labor Mobilization: The state needed to command a huge workforce, likely through a system of labor tribute similar to the later Inca mita.

- Resource Management: A complex bureaucracy was required to quarry stone, produce mortar, and provide food and housing for thousands of workers.

The internal structure of these cities is just as revealing. They were typically divided into repeating rectangular compounds, or canchas, enclosed by towering stone walls. These walls, some reaching up to 12 meters (40 feet) high, had few entrances, creating a labyrinthine and highly controlled environment. There were no grand public plazas or open markets for spontaneous gatherings. Movement was funneled, monitored, and restricted. The architecture itself was a tool of social control.

Within these compounds, archaeologists have found evidence of specialized sectors: administrative halls, workshops for skilled artisans, barracks for soldiers, and, crucially, vast storage facilities known as colcas. These warehouses were used to store food, textiles, and other goods collected as tribute, acting as the economic engine of the empire.

Case Studies in Stone: Pikillacta and Viracochapampa

Pikillacta: A Perfect Grid

Perhaps the most stunning example of Wari urban planning is Pikillacta (“Flea City” in Quechua, a name referring to its many small buildings), located in the Cusco Valley—the future heartland of the Inca Empire. Pikillacta is an almost perfect rectangle, its interior filled with over 700 buildings arranged in a relentless grid. Its outer walls are immense, creating a formidable fortress-like impression.

For years, the purpose of Pikillacta was a mystery. Early excavations found remarkably few domestic artifacts, leading some to believe it was a giant, empty “Potemkin village” meant only to intimidate. More recent research, however, suggests it was a multi-functional administrative center, garrison, and feasting site for local elites, deliberately built to establish Wari dominance in a strategic region. Its construction announced, in no uncertain terms, that a new power was in charge.

Viracochapampa: An Unfinished Ambition

Far to the north, near the modern city of Huamachuco, lie the ruins of Viracochapampa. It shares the classic Wari grid layout and architectural style of Pikillacta but with a fascinating twist: it was never finished. The walls stand incomplete, and doorways were never sealed with lintels. For reasons still debated—perhaps over-extension of imperial resources, local resistance, or the beginning of the empire’s decline—the project was abandoned.

Viracochapampa serves as a powerful symbol of both the scope of Wari ambition and the eventual limits of their power. It shows an empire in the process of expansion, actively stamping its administrative model across the landscape, until something brought the construction to a halt.

The Legacy for the Inca

When the Wari empire collapsed around 1000 AD, its cities were abandoned. But its ideas endured. The Inca, who rose to power a few centuries later, did not copy the Wari grid-plan city model; their urbanism was more organic, adapting cities like Cusco to the sacred landscape.

However, the Inca were the direct inheritors of the Wari administrative and ideological blueprint. They adopted and scaled up many of the core concepts of Wari statecraft:

- The concept of a centralized, expansionist empire.

- State-sponsored road networks (the famous Qhapaq Ñan was built upon many earlier Wari routes).

- Massive state storage systems (the Inca qullqa are direct descendants of the Wari colca).

- Systems of labor tribute to fuel state projects.

- The use of administrative centers to govern distant provinces.

In essence, the Wari provided the imperial playbook. They demonstrated how to rule a vast and diverse Andean territory through infrastructure, bureaucracy, and an ideology of order. The Inca, brilliant students of history, took these lessons and built an even larger, more integrated empire upon the foundations their predecessors had laid.

The next time you see an image of an Inca ruin, remember the ghosts of the Wari. Their story is a crucial reminder that history is built in layers. Long before the famous names we know, other civilizations were dreaming, planning, and building. The Wari grid-cities are their enduring, silent testament—a geometric legacy of power etched into the Peruvian landscape.