The Wari did not leave behind a celebrity ruin like Machu Picchu, but their legacy is etched into the very fabric of the Andean landscape. Through masterful infrastructure, sophisticated agriculture, and a clever political strategy, they built the first great expansionist empire of the Andes, laying the groundwork upon which the Inca would later build their fame.

A New Power in the Highlands

The Wari Empire emerged during what archaeologists call the Middle Horizon period. Its heartland was the Ayacucho Basin, a high-altitude region in Peru’s central highlands. From their sprawling capital city, Huari, this new state began to project power outwards. Huari was a massive urban center for its time, covering several square miles and potentially housing tens of thousands of people. It was a bustling nexus of political power, religious ceremony, and craft production, with distinct sectors for elites, artisans, and religious precincts.

During the same period, another great power, the Tiwanaku state, flourished to the south around the shores of Lake Titicaca. For a long time, historians believed they might have been two parts of a single empire, but the consensus today is that they were distinct, powerful neighbors. They shared some iconography and traded with one another, but they also competed for influence, representing two different models of state power in the Andes.

The Blueprint of Empire: Infrastructure and Administration

The Wari’s genius was not just in conquest, but in consolidation and control. They understood that to rule a diverse and rugged territory, you needed to connect it, feed its people, and make the state’s presence undeniably felt. Their solution was a three-pronged approach of masterful infrastructure.

1. The First Great Andean Road System

Long before the Inca’s famous Qhapaq Ñan (the “Royal Road”), the Wari built an extensive and sophisticated road network. These weren’t simple footpaths; they were engineered thoroughfares designed for efficiency. The roads connected their capital, Huari, to far-flung provincial outposts. This network was the empire’s circulatory system, allowing for the rapid movement of armies, administrators, and official messengers (the precursors to the Inca chasquis). More importantly, it enabled the efficient transport of goods, funneling tribute like textiles, food, and exotic materials back to the capital and distributing state-produced goods to the provinces.

2. Masters of the Mountain: Terraced Agriculture

How do you sustain a large, non-agricultural population of soldiers, bureaucrats, and artisans in the steep, challenging terrain of the Andes? The Wari perfected the answer: terraced agriculture. They constructed vast systems of stone-walled terraces, known as andenes, transforming precipitous mountainsides into fertile, arable farmland. These engineering marvels weren’t just about creating flat space; they were sophisticated hydrological systems that optimized water usage, prevented soil erosion, and created microclimates that could support diverse crops like maize, potatoes, and quinoa. This agricultural surplus was the economic engine of the empire, funding its expansion and supporting its urban centers.

3. Imposing Order: The Grid-Plan Administrative Centers

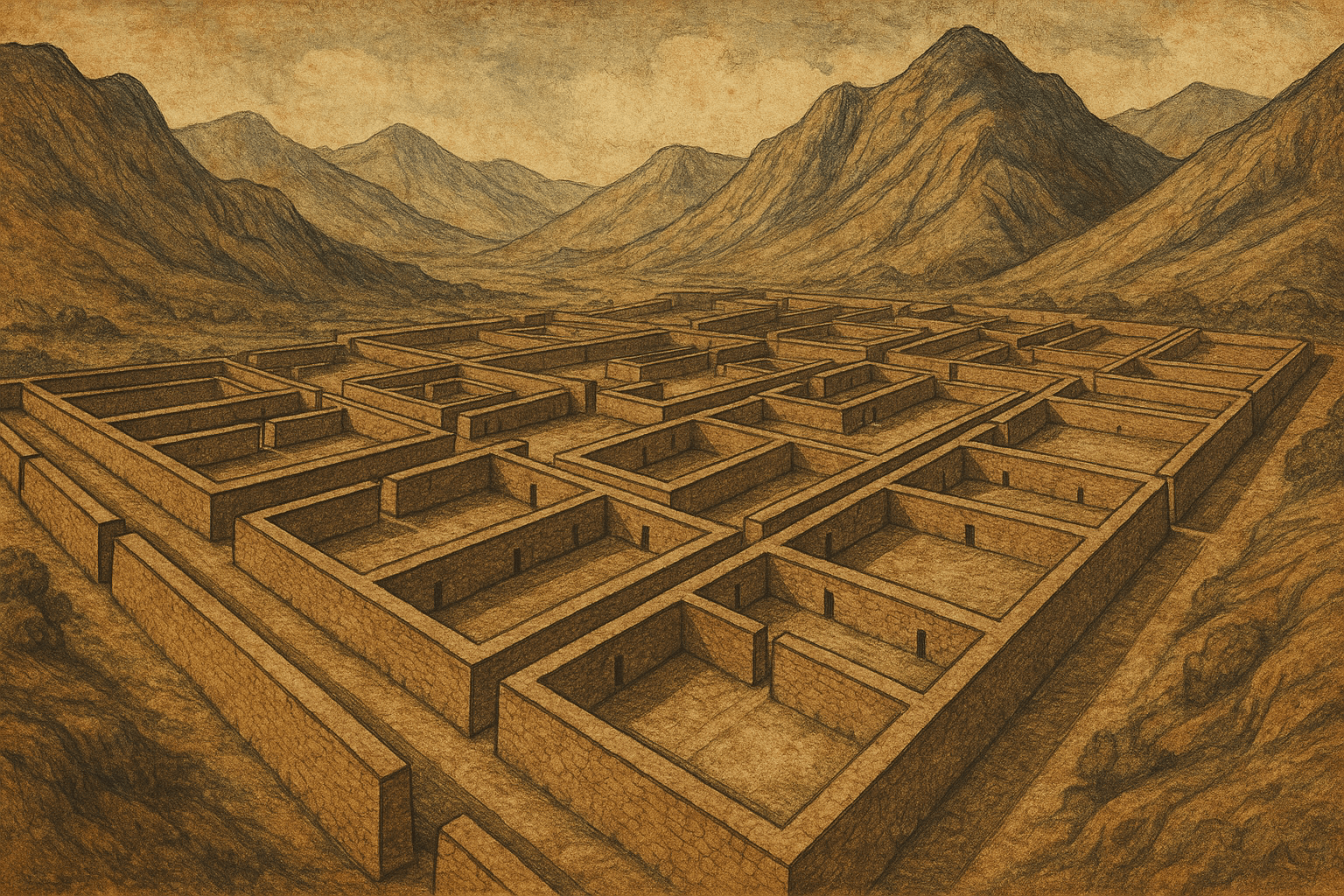

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Wari imperialism was their unique architectural signature: the grid-plan administrative center. In key strategic locations across their empire, the Wari built massive, pre-planned compounds that were unlike anything seen before. These were not organic cities that grew over time; they were imposing state installations dropped directly onto the landscape.

Classic examples include Pikillacta, near modern-day Cusco, and Viracochapampa in the north. These sites are characterized by towering perimeter walls enclosing a labyrinthine grid of rectangular buildings, long corridors, and vast open patios. Many of the structures appear to have been storehouses (qullqas) for grain and other goods. These centers served multiple functions:

- Symbols of Power: Their enormous scale and rigid, foreign design were a clear and intimidating statement of Wari dominance.

- Administrative Hubs: They were the regional seats of government where imperial officials oversaw tribute collection and managed state resources.

- Economic Nodes: They served as collection and redistribution points for the empire’s wealth.

By building these centers, the Wari created physical manifestations of their state ideology, projecting order and control across hundreds of miles.

A Strategy of Indirect Rule

The Wari did not simply march in and replace every local leader. Instead, they often employed a more subtle and efficient strategy of indirect rule. They would co-opt local elites, inviting them into the Wari political and economic system. Local chiefs could maintain their status and a degree of autonomy as long as they demonstrated loyalty, ensured tribute was paid, and facilitated Wari state projects.

Feasting and religion played a key role. At their administrative centers, Wari officials would host massive feasts for local leaders, using stores of food and chicha (maize beer) to build alliances and demonstrate the state’s wealth and generosity. They also spread their religious iconography—featuring a prominent Staff God—which blended with local traditions. This strategy of incorporation, rather than outright replacement, allowed the Wari to manage a vast and ethnically diverse empire with remarkable efficiency.

The Fading Empire and Its Enduring Legacy

Around 1000 AD, after four centuries of dominance, the Wari empire began to unravel. The exact reasons for its collapse are still debated, but evidence points to a combination of factors, including severe, prolonged droughts that would have strained their agricultural base and weakened the central government’s ability to provide for its people. This likely led to internal strife and rebellions from provinces no longer willing to submit to a weakened core.

The great administrative centers like Pikillacta were ritually abandoned, and the Wari state fragmented. But their legacy did not vanish. The Wari had fundamentally reshaped the Andean world. They proved that it was possible to unite the coast and the highlands under a single political authority.

Two centuries later, another group of highlanders—the Inca—would rise from the Cusco valley, right next door to the old Wari center of Pikillacta. It is no coincidence that the Inca Empire adopted and scaled up many of the Wari’s innovations: the road system, the terraced agriculture, the state-sponsored feasts, the massive storage system, and the strategy of co-opting local elites. The Wari were the pioneers. They drew the map and wrote the imperial playbook that would guide the Andes for the next 500 years. To truly understand the Inca, we must first look to their remarkable predecessors: the Wari, the first great masters of the Andes.