In the early 19th century, the Great Plains of North America were a sea of grass, and moving through it was a force of nature unlike any other: the American bison. Numbering an estimated 30 to 60 million, these colossal herds shaped the very landscape they inhabited. For the Plains Indian nations—the Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, and others—the bison, or Tȟatȟáŋka, was more than an animal. It was the source of life, the foundation of culture, and the center of their spiritual universe.

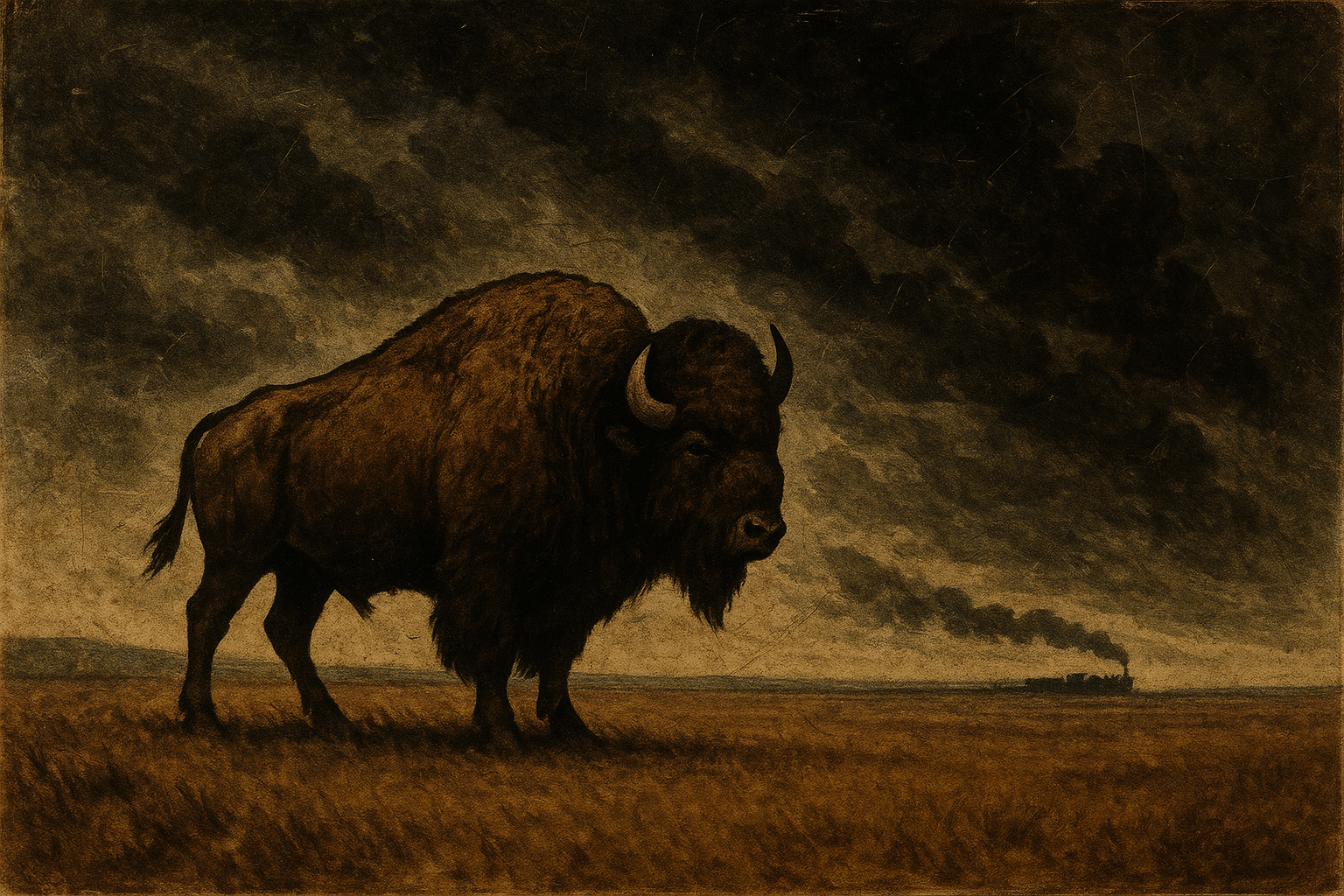

The story of the bison’s near-annihilation is often told as a tragic consequence of westward expansion and market hunting. But that is only half the truth. The slaughter of the great herds was also a calculated, brutal, and chillingly effective act of war—a deliberate strategy by the United States government and military to subjugate the Plains tribes by destroying their world.

The Walking Commissary

For the people of the Plains, the bison was a “walking commissary.” Its existence was so intertwined with their own that every part of the animal was used. The list is a testament to their ingenuity and deep respect for the resource:

- Food: The meat, rich and lean, was eaten fresh or preserved as jerky and pemmican, providing sustenance through harsh winters.

- Shelter: Tanned hides, expertly stitched together, formed the coverings for tipis, providing durable, weather-proof, and mobile homes.

- Clothing: Hides, with the hair left on or scraped off, were fashioned into robes, leggings, shirts, and moccasins.

- Tools and Weapons: Bones became scrapers, awls, and knives. Horns were shaped into cups, ladles, and decorative headdresses. Sinew was used as strong thread for sewing and for bowstrings.

- Fuel: Dried dung, or “buffalo chips”, was a crucial, smoke-free fuel source on the largely treeless plains.

Beyond the material, the bison was woven into the fabric of their spiritual lives. It featured in sacred ceremonies, origin stories, and the Sun Dance. To hunt the bison was a sacred act, undertaken with reverence. The animal was the cornerstone of their economy, culture, and independence.

The Tides of Destruction

The forces that would doom the great herds arrived on iron rails. As the Transcontinental Railroad and its offshoots pushed west after the Civil War, they brought with them a tide of change that would scour the plains clean.

First came the “sport” hunters. Wealthy easterners and European nobles would ride the trains, shooting bison by the hundreds from the comfort of their rail cars, often leaving the massive carcasses to rot where they fell. This wanton slaughter was wasteful, but it was the professional hide hunters who unleashed the true industrial-scale destruction.

A new tanning process developed in the East created a voracious demand for bison hides to make industrial machine belts, leather goods, and warm robes. Organized teams of hunters, armed with powerful, long-range rifles like the .50-caliber Sharps, descended on the plains. A single hunter could kill over 100 bison in a day, taking only the skin and sometimes the tongue, a delicacy. The railroads that brought the hunters west then carried the stacked, stinking hides east by the tens of thousands. By the mid-1870s, the once-unified great herd had been split by the railroad into a northern and southern herd, making them easier to eradicate.

“Every Buffalo Dead is an Indian Gone”

The U.S. Army, engaged in a series of brutal wars with the highly mobile and formidable Plains warriors, watched this commercial slaughter with keen interest. They had struggled for years to force the tribes onto reservations. Commanders on the ground quickly realized what the hunters were accomplishing for them. By destroying the bison, they were destroying the Indians’ ability to resist.

This was not a covert idea; it was an openly discussed and supported military strategy. The U.S. government became a willing, and often active, partner in the extermination.

General Philip Sheridan, commander of the Department of the Missouri, was one of the policy’s most outspoken advocates. At a meeting in Fort Dodge, Kansas, he is reported to have told an assembly of hunters:

“These men have done more in the last two years, and will do more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last thirty years… For the sake of a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle.”

Colonel Richard Irving Dodge was even more blunt in 1867, stating, “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

The government’s complicity was absolute. The Army often provided ammunition to the hunters. When a bill came before Congress in 1874 to protect the rapidly vanishing bison, it was passed by both the House and the Senate. But President Ulysses S. Grant, swayed by the arguments of his military advisors and Interior Department, refused to sign it, letting it die through a pocket veto. Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano had made his department’s position clear, arguing that he “would not be sorry” if the bison were exterminated, as it would be the “only way to bring about a permanent peace and allow civilization to advance.”

The Aftermath: An Empty Land, A Broken People

The result of this campaign was apocalyptic. The numbers are staggering. In 1870, millions of bison still roamed. By 1885, the southern herd was gone. By 1889, only a few hundred individuals remained in the entire United States, mostly huddled in the remote Pelican Valley of what would become Yellowstone National Park.

The plains fell silent. The ecological devastation was immense. Without the bison’s grazing, wallowing, and fertilizing, the prairie ecosystem was thrown into chaos. But the human cost was even greater.

For the Plains tribes, the extermination was nothing short of cultural and economic genocide. Deprived of their primary food source and the foundation of their way of life, bands of starving people were forced to surrender. One by one, proud and independent nations were herded onto reservations, dependent on government rations that were often inadequate and corruptly managed. Their freedom, their sacred connection to the land, and their entire world had been deliberately destroyed.

A Symbol of Resilience

The story of the American bison is a stark reminder of how warfare can be waged not just on people, but on the very ecologies that sustain them. The war on the bison was a war on Native Americans, prosecuted with bullets and tacit government approval, as surely as any cavalry charge.

Yet, the story does not end in total annihilation. Through the tireless efforts of early conservationists and, more recently, the leadership of tribal nations through organizations like the InterTribal Buffalo Council, the bison has begun a remarkable comeback. Today, herds once again graze on tribal and public lands, a powerful symbol of resilience, survival, and the enduring connection between a people and an animal. The bison’s return is more than an ecological success; it is an act of cultural restoration, a living monument to a history that must never be forgotten.