From Protecting People to Pausing War

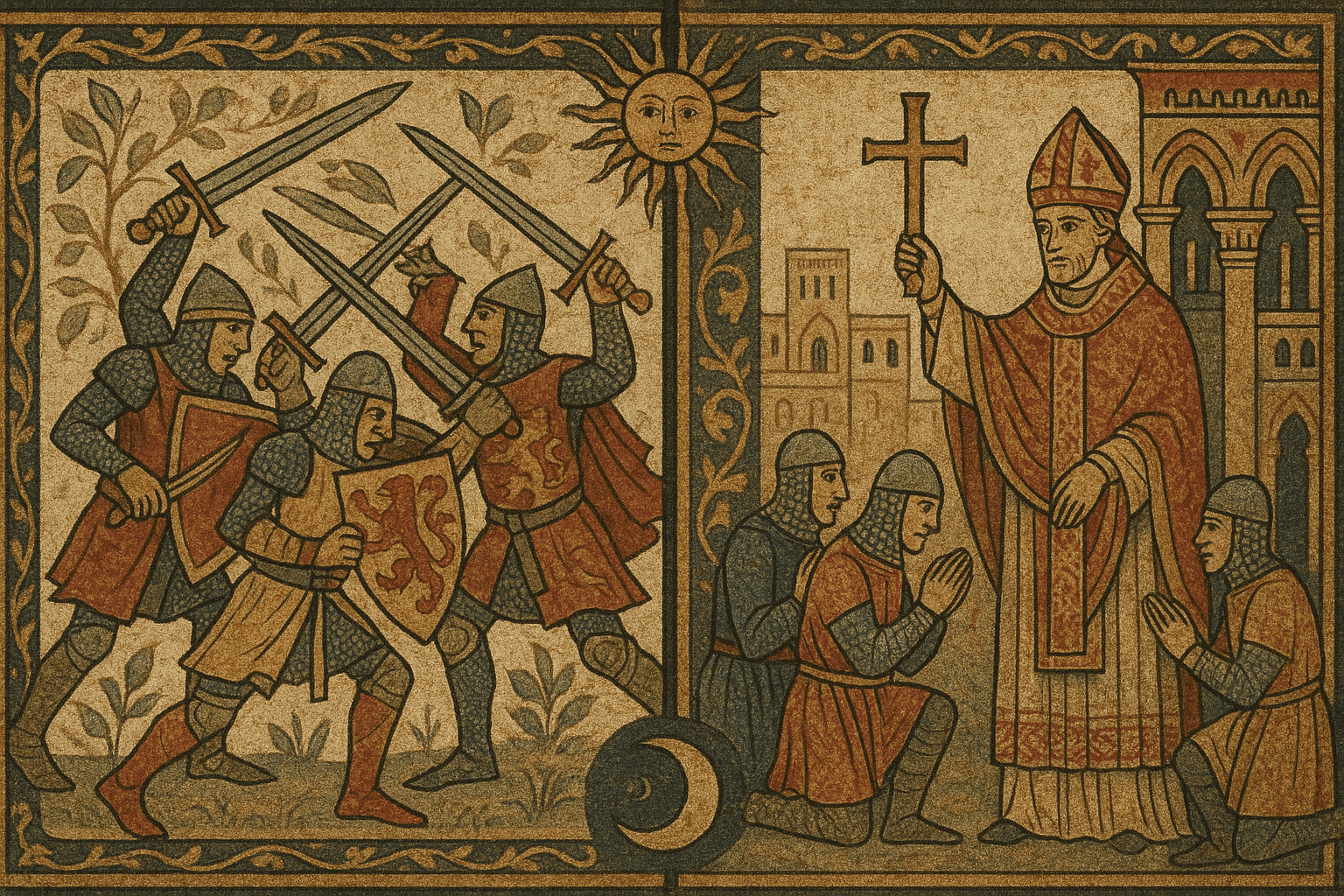

The Truce of God, or Treuga Dei in Latin, was not the Church’s first attempt to curb the endless violence. It grew out of an earlier, related movement known as the Peace of God (Pax Dei). First emerging in southern France at the end of the 10th century, the Peace of God was essentially a set of rules protecting non-combatants. Church councils declared that knights and lords who attacked unarmed clerics, peasants, merchants, women, or children—or who damaged church property, mills, and farms—would face divine wrath and the immediate penalty of excommunication.

The Peace of God was a crucial first step. It sought to create safe zones and protect the vulnerable backbone of society from the warrior class. However, it did little to stop the warriors from fighting each other. A lord could honor the Pax Dei scrupulously, leaving priests and peasants unharmed, while still spending his week waging a destructive private war against his neighbor. A new solution was needed, one that tackled the act of fighting itself. This was the Truce of God.

The Sacred Calendar of Conflict

The Truce of God was revolutionary in its simplicity and its audacity. Instead of designating who was off-limits, it designated when was off-limits. The movement began in the 1020s in Catalonia and quickly spread. Initially, it simply forbade warfare on Sundays, the day of the Lord’s resurrection. But as the movement gained momentum, its scope expanded dramatically.

By the mid-11th century, the Truce of God had reached its most common form. Fighting was typically forbidden from the ninth hour on Saturday until the first hour on Monday. Soon, this was extended further. A council in 1041 extended the period to run from sunset on Wednesday to sunrise on Monday. This meant that any kind of fighting, from a full-scale siege to a simple armed skirmish, was prohibited for more than half the week.

Furthermore, the Truce covered entire seasons of the liturgical year. All military activity was to cease during:

- Advent: The period of preparation leading up to Christmas.

- Christmastide: The season celebrating the birth of Jesus.

- Lent: The forty days of penance before Easter.

- Eastertide: The fifty days of celebration following Easter Sunday.

When you combined the weekly prohibitions with the long seasonal ones, a significant portion of the year—perhaps more than two-thirds of it—was theoretically rendered free of conflict. This attempted to fundamentally alter the rhythm of medieval life, subordinating the patterns of warfare to the calendar of the Church.

Enforcing God’s Ceasefire

Declaring a truce is one thing; enforcing it is another entirely. The Church lacked a standing army or a police force. Its primary weapon was spiritual, but it was a weapon that held immense power in a deeply religious society: the threat of excommunication.

For a medieval noble, excommunication was not a trivial matter. It meant being outcast from the community of the faithful. An excommunicated lord could not receive the sacraments, be married in a church, or be buried in consecrated ground. His oaths of fealty could be declared void, encouraging his vassals to rebel. His rivals could feel justified in attacking him as an enemy of God. At local councils, bishops would have entire assemblies of knights swear oaths on holy relics to uphold and enforce the Truce. Breaking such a public, sacred oath was a grave sin that put one’s immortal soul in peril.

The movement also gained support from powerful secular rulers who saw it as a useful tool. A king or powerful duke could use the Truce of God to consolidate his own authority and crack down on the private wars of his unruly vassals. William the Conqueror, for instance, successfully imposed the Truce in his Duchy of Normandy, helping to make it one of the most stable and centralized territories in Europe before he even set his sights on England.

A Double-Edged Legacy: Peace at Home, War Abroad

So, was the Truce of God successful? The answer is complex. It certainly did not end medieval warfare. Ambitious and powerful lords frequently ignored it when it suited their purposes, and enforcement remained inconsistent. The “public” wars waged by kings against other kingdoms were generally considered exempt.

However, the Truce was far from a failure. It significantly reduced the level of day-to-day anarchic violence. It gave communities breathing room, allowing agriculture and commerce to stabilize. It powerfully reinforced the moral authority of the Church, positioning it as the ultimate arbiter of right and wrong, even in matters of war.

Perhaps most profoundly, the Truce of God helped to channel the martial energies of the European knightly class. It was a key element in the development of the chivalric code, which fused warrior status with Christian duty and the concept of righteous violence. If a knight’s violent impulses were to be constrained at home, they needed an outlet elsewhere.

This led directly to one of the most defining events of the Middle Ages. In 1095, at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II gave a fiery sermon. In that same speech, he both reaffirmed the Truce of God for all of Christendom and called upon the knights of Europe to redirect their swords. He urged them to stop fighting their Christian brothers and instead embark on an armed pilgrimage to the Holy Land to liberate it from Muslim control. The First Crusade was born.

The Truce of God, therefore, stands as a monumental medieval effort to manage human conflict. While it did not create a utopia of peace, it successfully curbed local violence, reshaped the ethics of war, and inadvertently set the stage for the pan-European military campaigns of the Crusades. It was a testament to the Church’s bold vision of a more ordered world, a sacred pause in an age of ceaseless war.