Before the first Spanish ships anchored off its coast, before the first movie studio was built, and long before the freeways wove their concrete tapestry across the landscape, Southern California was a world of profound natural abundance and human ingenuity. For thousands of years, this land, known to its people as Tovaangar, was the exclusive home of the Tongva. Their story is not a prelude to the history of Los Angeles; it is the foundational epic upon which all subsequent chapters are written.

A Land of Abundance: The World of Tovaangar

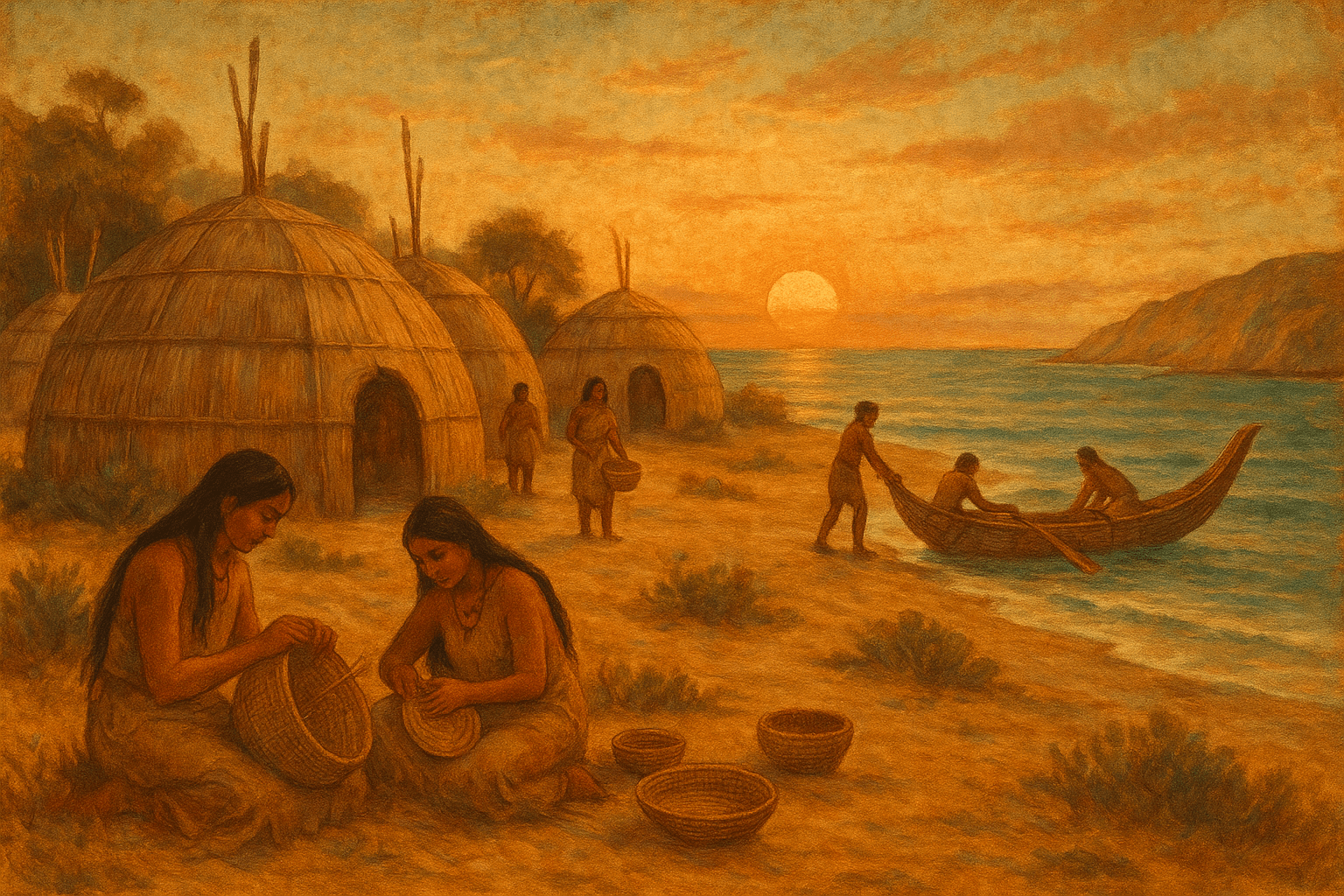

The Tongva territory was vast and diverse, stretching from the San Gabriel Mountains to the Pacific Ocean and encompassing the Southern Channel Islands, including Pimu (Santa Catalina) and Kinkipar (San Clemente). This was not a wilderness to be tamed, but a home to be lived in partnership with. The Tongva were masters of this environment, their lives intricately tied to the rhythms of the land and sea.

Their society was sustained by a deep ecological knowledge. Inland, the mighty oak tree was a cornerstone of life. The Tongva harvested acorns in massive quantities, developing a sophisticated process to leach out the bitter tannins, grinding the nuts into a flour that served as a nourishing staple for porridge and bread. Their understanding of botany was extensive, and they utilized a wide array of plants for food, medicine, and tools, including:

- Yucca: The fibers were used for making sandals and rope, while the root was a source of soap.

- Elderberries and Chia Seeds: Valued as important food sources.

- White Sage (Qas’ily): A sacred plant used for spiritual cleansing and ceremonies.

On the coast and islands, the Tongva were expert mariners. Their most remarkable technological achievement was the te’aat, a sewn-plank canoe. Unlike dugout canoes, these vessels were crafted from driftwood planks, which were painstakingly shaped, sewn together with plant fibers, and sealed with a natural asphaltum (tar) that seeped up from the ground. The te’aat was light, fast, and seaworthy, enabling the Tongva to navigate open ocean channels, fish for tuna and swordfish, hunt sea mammals, and maintain a vibrant trade network with the island communities.

A Complex and Ordered Society

Far from the simplistic stereotype of “hunter-gatherers”, the Tongva lived in a highly organized and stratified society. Their world was a network of as many as 100 autonomous, yet interconnected, villages. One of the largest and most significant was Yaanga, situated near what is now Union Station in downtown Los Angeles.

Each village was governed by a Tomyaar, a hereditary chief who held political and religious authority. This leadership was not despotic; the Tomyaar governed with the counsel of village elders. Society also included a wealthy elite, a middle class of artisans and workers, and a system of lineage and kinship that dictated social standing.

Commerce was central to Tongva life. They were part of a sprawling trade network that extended to the Mojave Desert, the Colorado River, and beyond. The currency of this economy was the shell bead, meticulously crafted from Olivella shells. Using their te’aat canoes, island Tongva traded high-quality steatite (soapstone) bowls and effigies, which were prized on the mainland. In return, mainland villages offered acorns, seeds, and animal hides. This constant exchange of goods also meant an exchange of ideas, news, and culture, binding the disparate villages of Tovaangar together.

The Spirit World: The Chinigchinich Religion

Spirituality was the heartbeat of Tongva existence, informing every aspect of their lives from harvesting practices to social customs. At the center of their religious world was the god Chinigchinich. Born, according to oral tradition, in the village of Puvunga (now the site of California State University, Long Beach), Chinigchinich provided the Tongva with a moral code and a set of laws for righteous living.

He taught that there were consequences for one’s actions, both in this life and the next. His laws outlined social prohibitions and dictated the proper way to live in balance with the cosmos. Important ceremonies and rituals were conducted in a sacred, circular enclosure known as the yovaar. Here, under the guidance of shamans and priests, the community would dance, sing, and make offerings to honor Chinigchinich and maintain cosmic order. This belief system fostered a deep respect for all living things and reinforced the idea of a reciprocal relationship with the natural world.

The Great Disruption: Contact and Colonization

The arrival of Spanish explorers in 1769, and the subsequent founding of the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel in 1771, marked a cataclysmic turning point for the Tongva. The Spanish forcibly relocated diverse village populations to the missions, stripping them of their autonomy and attempting to erase their identity. It was here that the Spanish renamed them based on the nearest mission, calling them “Gabrieliño” and “Fernandeño.”

Within the mission walls, the Tongva were subjected to forced labor, cultural suppression, and devastating European diseases to which they had no immunity. Their population, once estimated to be between 5,000 and 10,000, plummeted. The Mexican and American periods that followed only intensified the loss of land, life, and sovereignty. The rich world of Tovaangar was systematically dismantled.

Enduring Legacy: The Tongva Today

For many years, the Tongva were spoken of only in the past tense. But they were never gone. Today, their descendants are fighting to reclaim their heritage and their voice. Despite the immense challenges, including the lack of federal recognition which denies them many rights afforded to other Native American tribes, the Tongva community is vibrant and resilient.

Cultural leaders are working tirelessly to revitalize the Tongva language, piece by piece, from ethnographic records and the memories of elders. The te’aat is being rebuilt and paddled once more in the waters off the coast. Tongva artists, activists, and educators are ensuring their story is heard, demanding a place at the table in modern Los Angeles.

Their legacy is also written on the very map of Southern California. Place names like Topanga, Tujunga, Cahuenga, and Azusa are all derived from Tongva words, silent reminders of the land’s original inhabitants. As you move through the bustling metropolis of Los Angeles, remember that you are walking on Tongva land. Their story is a powerful testament to survival, resilience, and the unbreakable bond between a people and their earth—the People of Tovaangar.