The Grisly Legend of the Tanchagem

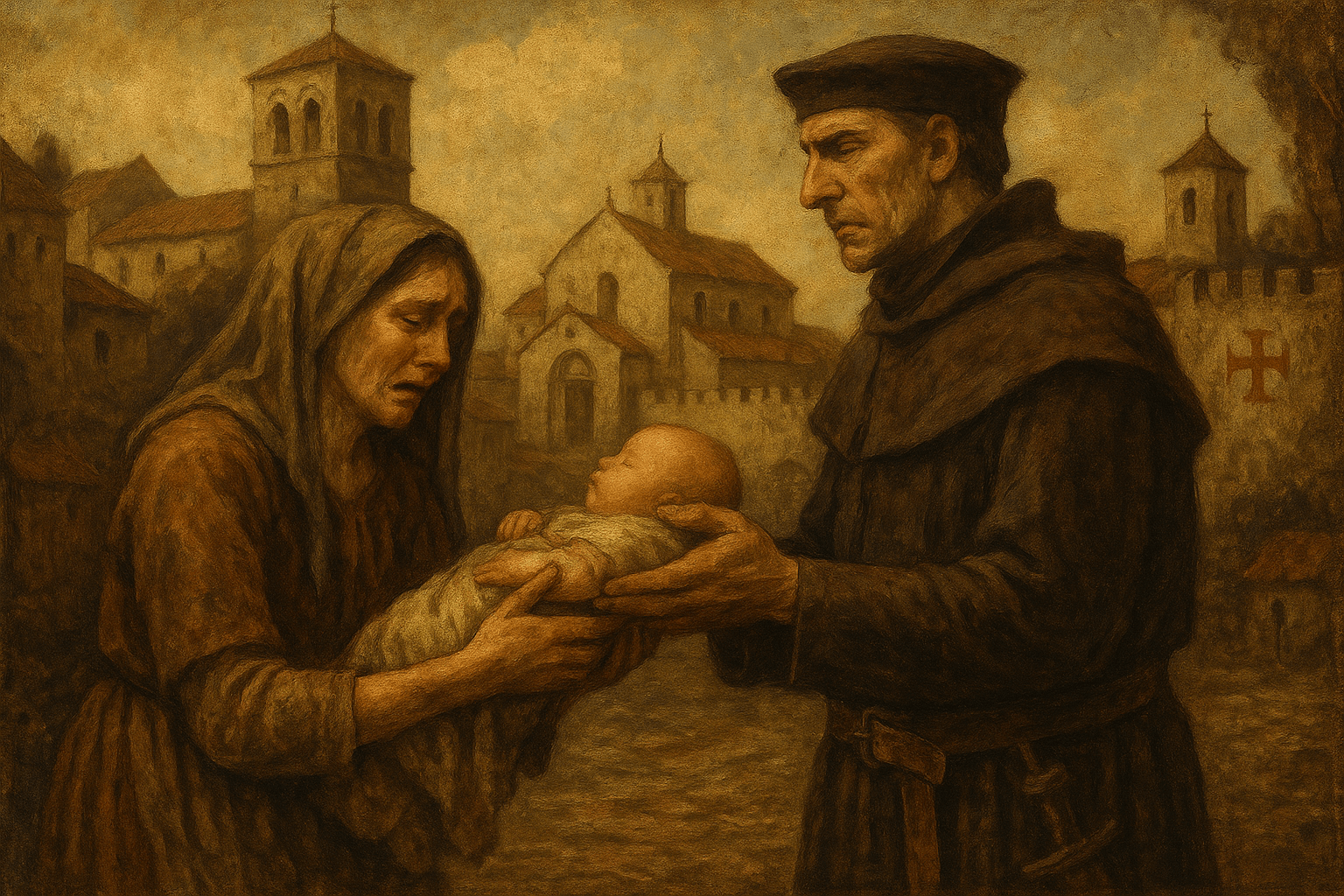

The story, as it has been told for nearly two centuries, centers on the remote northern Portuguese town of Castro Laboreiro. According to the legend, the town’s medieval charter, or foral, contained a unique and terrifying clause. When a peasant woman married and gave birth to her first child, the local lord had the right to take the infant as a form of tax. The parents’ only recourse was to “redeem” their own child by paying a hefty fee, effectively buying their baby back from the man who owned their land.

This horrifying practice was brought to popular attention by one of Portugal’s most celebrated historians, Alexandre Herculano, in his monumental 19th-century work, História de Portugal. Herculano, a product of the Romantic era that often painted the Middle Ages in the darkest possible hues, described the tanchagem as a “barbaric tribute”, an example of the absolute and arbitrary power wielded by a decadent feudal nobility over a helpless peasantry.

Coming from a figure of Herculano’s stature, the story stuck. It became a powerful symbol of feudal oppression, often cited alongside the equally infamous (and largely mythical) droit du seigneur—the supposed “right of the first night.” But is the story true?

A Tale of Historical Misinterpretation?

For modern historians, the electrifying tale of a “baby tax” raises immediate red flags. When they went back to the primary source Herculano used—the 12th-century foral of Castro Laboreiro—they found a more ambiguous picture. A foral was a royal charter that established a council’s rights, privileges, and, crucially, its tax obligations. These documents were legalistic and often written in dense, abbreviated Latin or Old Portuguese.

The clause in question refers to a woman who “fecerit tanchagem” (performs the tanchagem) with her firstborn. The entire controversy hinges on the meaning of that single, obscure word: tanchagem.

Herculano interpreted it in its most brutal, literal sense. But there was no other evidence from anywhere else in Portugal or Europe of a tax paid with human children. While lords had immense control over their serfs’ lives—dictating who they could marry, where they could live, and what labor they must perform—the systematic seizure of infants was a step too far, an act that would have destroyed the very workforce a lord depended on. This lack of corroborating evidence has led most scholars to conclude that Herculano, influenced by his anti-feudal biases, had made a dramatic misinterpretation.

What Was the Tanchagem in Reality?

If not a human sacrifice to the lord’s treasury, what was the tanchagem? The likely answer is far more mundane, though it still sheds light on the social dynamics of the time. The root of the word, tanchar or tancar, means “to fix”, “to secure”, or “to close.” Based on this, historians have proposed several more plausible explanations.

A Tax on Marriage or Lineage

The most widely accepted theory is that the tanchagem was a monetary fee related to securing the legal status of the firstborn child. It may have been one of the following:

- A Registration Fee: The payment could have been a fee to formally register the firstborn as a legitimate heir, ensuring their right to inherit their family’s meager possessions and their place within the community. In this sense, it was a tax to “secure” the child’s lineage.

- A Fine for Out-of-Wedlock Births: Some interpretations suggest the tanchagem was a penalty levied on a woman who had her first child outside of marriage, a way for the lord to “close” the legal and moral transgression.

- A Fee for Marrying Outside the Domain: Like the French formariage, it might have been a tax paid when a woman married a man from outside the lord’s territory, compensating the lord for the “loss” of a subject and her future children.

In all these scenarios, the payment was in coin or kind (like a head of livestock), not a person. The reference to the “firstborn child” was not because the child was the payment, but because the child’s birth was the event that triggered the payment.

Why Did the Myth Take Hold?

If the tanchagem was just a peculiar local tax, why did the story of baby-stealing lords become so popular? The answer lies in the 19th century’s relationship with the past. The Romantic movement and rising liberal thought idealized the nation-state and viewed the feudal era as a time of tyrannical, fragmented power that had to be overcome.

A story like the tanchagem was the perfect propaganda. It painted feudal lords not just as economically oppressive, but as morally monstrous. It created a clear narrative of good versus evil—the suffering peasant family versus the predatory noble—that resonated with a public eager to believe in the progress of their own “enlightened” age. Herculano’s immense reputation cemented the myth in the national consciousness, and its sheer shock value ensured its survival.

A Lesson in History

The formal practice of the tanchagem, whatever it truly was, was officially abolished in the early 16th century when King Manuel I reformed and standardized the forais across Portugal. By then, the custom itself had likely fallen into disuse.

Today, the story of the tanchagem serves as a fascinating historical case study. It reminds us that the past is not a fixed storybook but a field of interpretation, where the biases of historians can be as influential as the sources themselves. The legend of the “ritual tax” tells us less about the specific laws of medieval Castro Laboreiro and more about the deep-seated anxieties surrounding power, family, and survival in the feudal world. It’s a chilling reminder of the lord’s reach into the most intimate corners of peasant life, even if that reach didn’t extend to the cradle.