Before the arrival of Columbus in 1492, the Taíno were the principal inhabitants of the Greater Antilles—islands we now know as Cuba, Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico, and Jamaica. Theirs was a sophisticated society with complex political structures, a rich spiritual life, and vibrant cultural traditions. At the very center of this culture was Batey.

The Court and the Game: How Batey Was Played

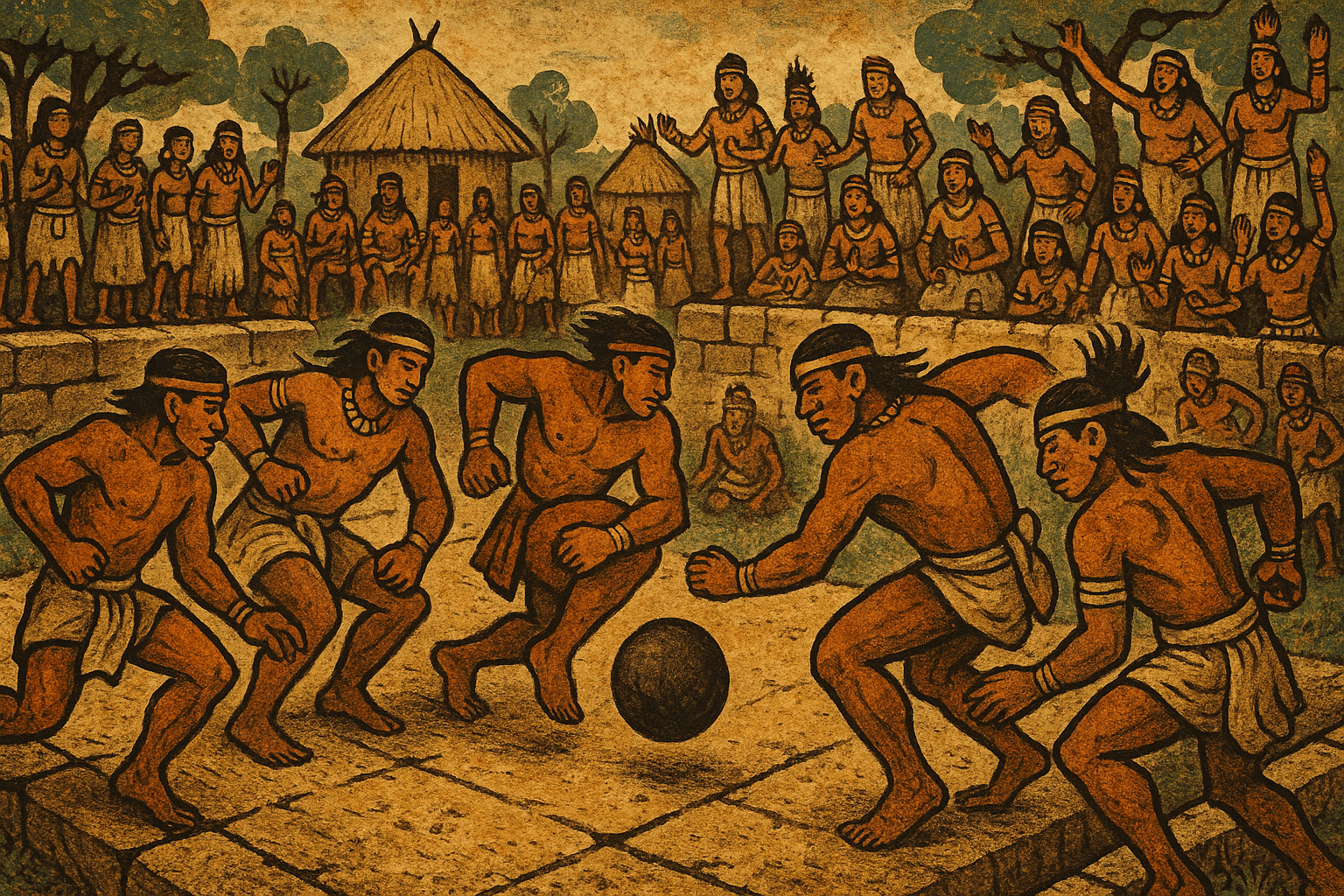

The game took place on a designated court, also called a batey. These were not simply flattened patches of dirt; they were carefully constructed ceremonial centers. Often rectangular in shape, the courts were enclosed by upright stone monoliths, some of which were intricately carved with petroglyphs depicting cemís—the gods, spirits, and ancestors central to Taíno religion. The Caguana Ceremonial Ball Courts Center in Puerto Rico, one of the most important archaeological sites in the Caribbean, features ten magnificent bateyes of varying sizes, standing as a testament to the game’s importance.

The rules of Batey share fascinating similarities with other ancient Mesoamerican ball games, though with distinct Taíno characteristics. Here’s a breakdown of the basics:

- The Teams: Two teams, with anywhere from 10 to 30 players each, would face off. While primarily played by men, historical accounts from Spanish chroniclers note that women also played, sometimes on their own teams and sometimes even against men.

- The Ball: The ball, called a batú, was made of solid rubber, crafted from the resin of the caoutchouc tree. This made it dense and bouncy, requiring immense skill to control.

- The Objective: The goal was to keep the ball in motion, volleying it back and forth between teams. The key rule was that players could not use their hands or feet. Instead, they used their hips, thighs, knees, shoulders, back, and head—any part of the body except the extremities.

The gameplay would have been a spectacular display of agility and power. Players would dive, spin, and contort their bodies to strike the heavy ball, propelling it toward the opposing team. A point was scored when the opposing team failed to return the ball or allowed it to touch the ground. The game was fast, physical, and captivating.

More Than a Sport: A Tool for Politics and Justice

While entertaining, the true significance of Batey lay far beyond the court. It was a deeply embedded socio-political institution that helped maintain harmony and order across the Taíno world.

One of its most critical functions was as a mechanism for dispute resolution. Instead of resorting to open warfare, which was costly and destructive, rival chiefdoms (cacicazgos) could settle their differences on the batey. A conflict over territory, hunting rights, or a personal grievance could be decided by the outcome of a game. The losing chief and his village would be honor-bound to accept the result. In this sense, Batey was a form of ritualized combat, a substitute for war that saved lives and preserved vital resources.

The game was also a powerful political tool for a cacique (chief). Hosting a Batey tournament was a way to display wealth, power, and prestige. A cacique would invite neighboring leaders, forging and reinforcing alliances through the shared experience of the game, the accompanying feasts, and ceremonial dances known as areytos. These events brought communities together, fostering a sense of collective identity and strengthening the social fabric of the islands.

The Spiritual Heart of the Game

Batey was inseparable from Taíno spirituality. The court itself was a sacred space, with the carved stones serving as a conduit for the cemís to witness and oversee the event. The game wasn’t just played for the community; it was performed for the gods.

Some historians and archaeologists theorize that the game held deep cosmological meaning. The movement of the rubber ball across the court may have symbolized the movement of the sun, moon, or other celestial bodies. The struggle between the two teams could represent mythical battles between gods or the dualistic forces of day and night, life and death. The players weren’t just athletes; they were participants in a sacred cosmic drama.

Unlike some of the more brutal ball games of mainland Mesoamerica (like the Mayan pitz), there is little conclusive evidence that Taíno Batey involved ritual human sacrifice. While some early Spanish accounts hint at it, the archaeological record has not confirmed this practice. For the Taíno, the “stakes” of the game were more often political and social rather than life and death for the players themselves.

The End of an Era and an Enduring Legacy

The arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 marked the beginning of the end for Batey and for Taíno society as a whole. The Spanish conquest brought disease, enslavement, and systematic violence that decimated the Indigenous population. As their culture was suppressed, traditions like Batey were driven to extinction.

Yet, echoes of the game and its world remain. The word batey survived in Caribbean Spanish, evolving to describe the open, cleared areas in sugar mill villages where workers gathered—a ghostly reminder of the original ceremonial plazas.

Today, as people across the Caribbean work to reclaim and revitalize their Indigenous heritage, there is a renewed interest in Batey. Cultural groups and descendants of the Taíno are studying the historical records and recreating the game, bringing its athletic grace and powerful spirit back to life. These revivals are more than historical reenactments; they are a powerful affirmation of cultural survival and identity.

The story of Batey is a poignant reminder of a lost world. It was a sport, a court of law, a political summit, and a religious ritual all in one. It demonstrates that for the Taíno people, a simple ball game could be the very thing that held their world together.