It was a rash act, but not an entirely uncommon one in a medieval university city. What happened next, however, was anything but common. This single, ill-tempered dispute over a pint of wine would ignite a simmering feud that would engulf the entire city in flames, turning the streets of Oxford into a three-day battlefield.

Town vs. Gown: A Feud Forged in Privilege

To understand how a bar fight could escalate into urban warfare, we must first understand the deeply fraught relationship between “Town” and “Gown.” This was the term for the perennial conflict between a city’s local inhabitants (the Town) and the university’s scholars and masters (the Gown, named for their academic robes).

The University of Oxford wasn’t just an educational institution; it was a powerful, semi-autonomous state within a state. Its scholars, many of whom were teenagers or young men from wealthy families across England and Europe, were granted “benefit of clergy.” This meant they were subject to the far more lenient Church courts, not the local civil courts. A student could commit a serious crime, even assault or murder, and often escape with a light penance, while a towns-person would face the full, brutal force of secular law.

This created a two-tiered justice system that bred immense resentment. The townsfolk saw the students as arrogant, privileged troublemakers who drank heavily, chased local women, ran up debts, and then hid behind their clerical status. Economic tensions also ran high. The university’s presence drove up prices for rent and food, and its charters gave it control over many local markets, directly impacting the livelihoods of local merchants and artisans.

For their part, the “Gown” often looked down on the “uneducated” locals with disdain. Riots and brawls were a regular feature of life in Oxford, but on St. Scholastica’s Day in 1355, the powder keg finally exploded.

From Tavern Brawl to Urban Warfare

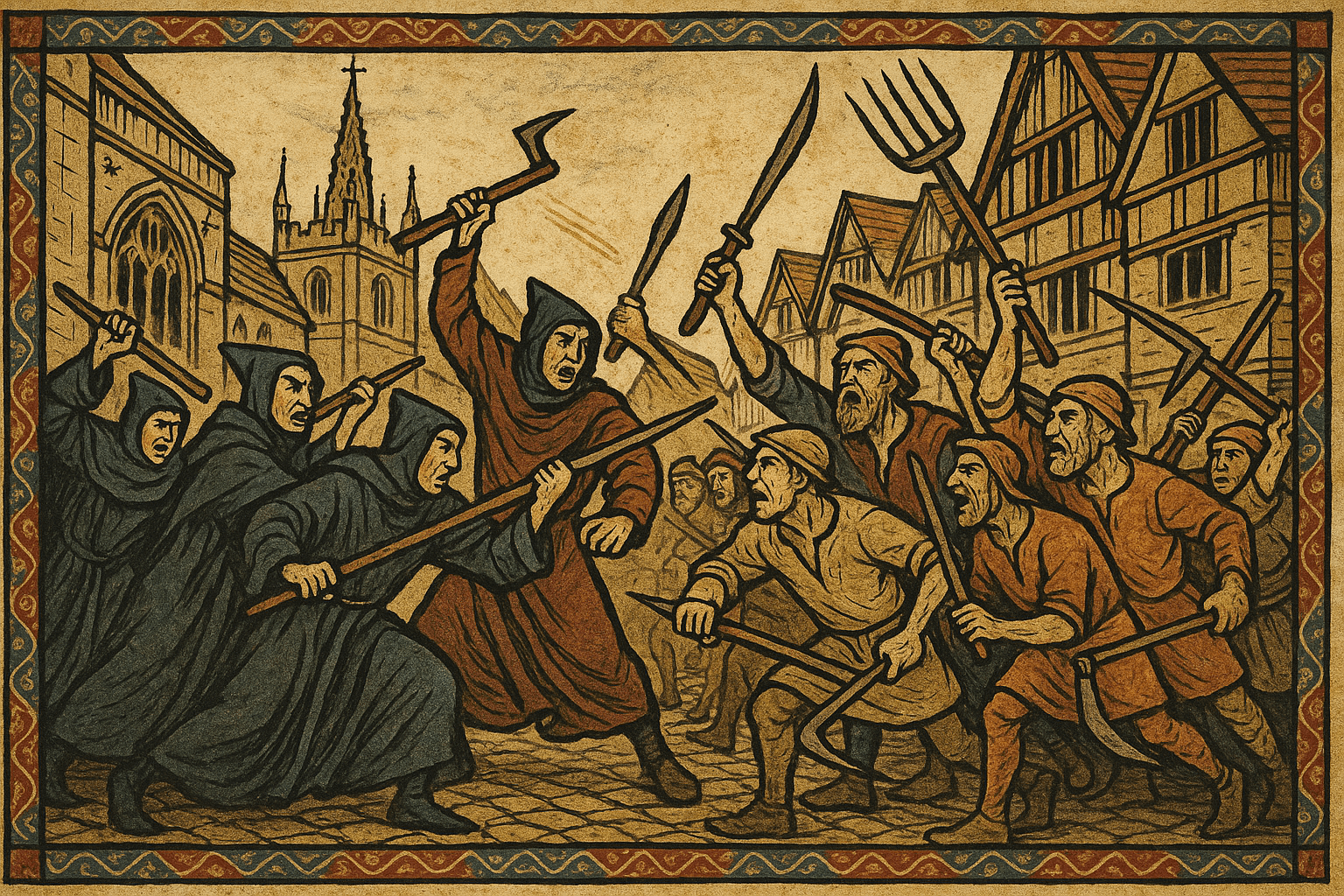

After the initial assault in the tavern, John Croidon rallied his neighbors. Other townsfolk, hearing the commotion, joined in. A brawl erupted between students and locals. The conflict might have ended there, but Oxford’s mayor, John de Bereford, escalated the situation dramatically. He reportedly rode to the nearby countryside, urging villagers to come to Oxford and “do what damage they could to the scholars.”

A crucial moment came when the city and university bells began to ring. The bell of the town’s church, St. Martin’s, pealed to summon the townsfolk. In response, the bell of the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin rang out, calling the scholars to arms. The lines were drawn.

What followed was a three-day massacre.

- Day One (Feb. 10): The initial brawls were chaotic but relatively contained. Scholars armed themselves with bows and arrows, firing on the mayor and his men from the tower of St. Mary’s.

- Day Two (Feb. 11): This was the bloodiest day. Around two thousand men from the countryside, reportedly shouting “Havoc! Havoc! Smyt fast, give gode knocks!”, poured into Oxford. They joined the townsfolk in a full-scale assault on the university’s academic halls and inns. They broke down doors, hunting for scholars. Those they found were beaten, maimed, or killed. Priceless books and manuscripts were torn apart and burned. An Augustinian friary was ransacked. Chroniclers reported horrific acts of violence, including scholars being scalped in mockery of their clerical tonsures.

- Day Three (Feb. 12): The violence continued, with roving bands of townsfolk hunting down any remaining scholars who hadn’t fled the city. By the time the bloodshed subsided, an estimated 63 scholars and about 30 locals were dead, though the true numbers are likely higher.

The King’s Justice and an Enduring Penance

When news of the riot reached King Edward III, he was furious. He immediately sent judges to investigate and dispense justice. Crucially, the King’s sympathies lay entirely with the university. The Crown saw institutions like Oxford and Cambridge as vital for training the administrators, lawyers, and clergy needed to run the kingdom. The town was, in his view, expendable.

The punishment for the town of Oxford was swift and severe.

The mayor and the town’s bailiffs were arrested and imprisoned. The city was placed under an interdict, meaning all religious services were suspended. A massive fine was levied against the town. Most importantly, a new Royal Charter was issued that solidified the university’s power for centuries to come. The university was granted jurisdiction over almost all aspects of city life: control of the markets, regulation of weights and measures, the power to tax bread and ale, and legal authority over all criminal cases involving students.

The town’s attempt to assert its rights had resulted in its complete and total subjugation. The final humiliation was the annual penance. Every year on St. Scholastica’s Day, for the next 470 years, the mayor of Oxford and 62 leading citizens had to march bareheaded through the city to the University Church, attend a Mass for the souls of the slain scholars, and pay a fine of one penny for each life lost. This ignominious tradition continued until 1825.

The Legacy of the Riot

The St. Scholastica Day Riot stands as the most extreme and violent episode in the long history of “Town vs. Gown” conflict. It’s a gripping, brutal story, but it’s more than just a medieval street fight. It’s a stark window into the social structures of the Middle Ages, revealing the deep resentments created by privilege, legal inequality, and economic power. The riot wasn’t truly about bad wine; it was about pride, power, and a desperate, bloody struggle for control that the town was destined to lose.