When we picture the Silk Road, our minds often conjure images of Chinese silk heading for Roman markets or camel caravans silhouetted against a vast desert sunset. But who was actually leading those caravans? Who braved the treacherous mountain passes and negotiated deals in a dozen different languages? For centuries, the answer was overwhelmingly: the Sogdians.

Often overlooked in popular history, the Sogdians were the undisputed masters of the Silk Road. They weren’t conquerors who built a sprawling empire of their own; they were something far more influential. They were the connective tissue, the middlemen, the cultural and economic brokers who made the ancient world’s most famous trade network hum with life. From their homeland in the heart of Central Asia, they created a commercial empire that stretched from the Byzantine Empire to Tang China, becoming the primary agents of cross-continental exchange.

Who Were the Sogdians?

The Sogdians hailed from Sogdiana, a fertile region nestled between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers in modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. This wasn’t a unified kingdom but a collection of dynamic, wealthy city-states, the most famous of which were Samarkand and Bukhara. As an ancient Iranian people, they spoke Sogdian, an Eastern Iranian language that would become a lingua franca along the eastern stretches of the Silk Road.

Their strategic location was their greatest asset. Positioned at the geographical crossroads of Asia, they were perfectly placed to act as intermediaries between four major civilizations: Persia to their west, India to their south, the nomadic steppe empires to their north, and, most importantly, China to their east. Instead of building armies, they built networks. Instead of conquering land, they conquered markets.

The Architects of a Commercial Empire

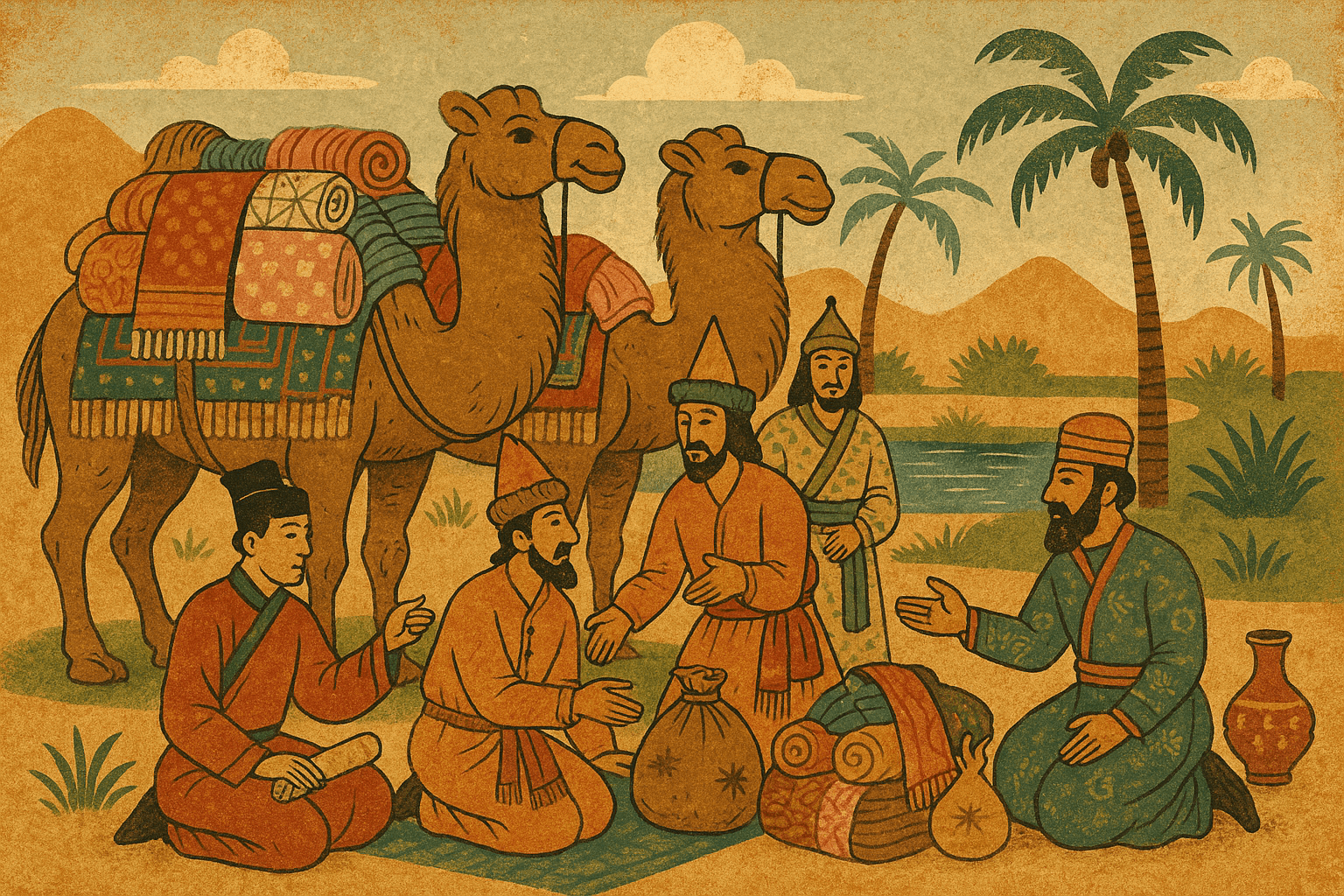

The key to Sogdian success was their sophisticated, diasporic network. All along the Silk Road, from the edges of the Byzantine Empire to the Chinese capital of Chang’an, Sogdians established tight-knit communities. These settlements weren’t just homes away from home; they were crucial logistical hubs. A Sogdian merchant leaving Samarkand could find fellow countrymen in Turfan, Dunhuang, or Luoyang who could provide lodging, storage for goods, fresh camels, local market intelligence, and translation services.

This network allowed them to dominate the trade in luxury goods. Their caravans, often consisting of hundreds of Bactrian camels, were mobile enterprises. They moved:

- From China: Silk was the ultimate prize. The Sogdians were the primary exporters of Chinese silk to the West, a monopoly they guarded fiercely. They also traded in paper, lacquerware, and manufactured goods.

- To China: They brought a world of exotic goods to the Chinese court, including Persian metalwork, Sassanian glassware, fine wines, rare spices and medicines from India, and powerful Central Asian horses, which were highly prized by the Chinese military.

But they were more than just long-distance haulers. The Sogdians were also skilled artisans in their own right, famous for their exquisite textiles and metalwork. Goods labeled as “Persian” or “Western” in Chinese records were often, in fact, Sogdian-made products, a testament to their marketing genius and craftsmanship.

Carriers of Culture, Faith, and Ideas

The Sogdians’ most enduring legacy may not be the goods they traded, but the ideas they carried in their saddlebags. As they moved between civilizations, they became conduits for an incredible exchange of culture, religion, and technology.

Religion: While many Sogdians practiced their native Zoroastrianism, their pragmatic and multicultural nature made them carriers for several world religions. They were instrumental in:

- Buddhism: Sogdian merchants and monks played a crucial role in translating Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit into Chinese and other languages, helping the faith take root in East Asia. Many were devoted patrons, funding the construction of monasteries and the creation of religious art.

- Manichaeism: This dualistic religion, originating in Persia, found some of its most enthusiastic followers among the Sogdians. They carried it eastward, where it became the official state religion of the powerful Uyghur Khaganate, a key Sogdian trading partner.

- Nestorian Christianity: Sogdians also helped transmit Nestorianism further into Asia, with churches ministering to their communities as far away as China.

Language and Art: The Sogdian language, and its versatile Aramaic-derived script, became a common language of commerce. In fact, the Sogdian alphabet became the parent script for several other Central Asian languages, including Old Uyghur, Mongolian, and Manchu, leaving a linguistic footprint that lasted for centuries. Their art, a vibrant fusion of Persian, Indian, and Chinese styles, influenced artistic tastes across the continent. Depictions of Sogdian musicians, dancers (performing the famous “Sogdian whirl”), and merchants can be found in tomb paintings and ceramics from China to Persia.

A Glimpse into Their Lives: The Ancient Letters

How do we know so much about the personal side of their lives? A remarkable archaeological find provides a window into their world. In the early 20th century, a mailbag lost in a watchtower near Dunhuang was discovered. It contained a collection of paper documents from the 4th century CE known as the “Sogdian Ancient Letters.”

These letters are not state documents but personal and business correspondence written by Sogdians living far from home. They speak of business deals, market conditions, and pleas for news. One heartbreaking letter is from a woman named Miwnay, abandoned in Dunhuang by her husband, writing to her mother about her desperate situation. These letters transform the Sogdians from abstract historical figures into real people, with families, ambitions, and anxieties much like our own.

The Fading of a Golden Age

The Sogdian dominance of the Silk Road lasted for nearly five centuries but began to wane in the 8th century CE. The Arab conquests of Central Asia brought Islam to the region, and over time, the Sogdians began to assimilate. They gradually adopted the Persian language (evolving into modern Tajik) and the Islamic faith. Simultaneously, political turmoil, such as the An Lushan Rebellion in China (which was instigated by a general of Sogdian descent), disrupted their networks. Eventually, the rise of maritime trade routes diminished the importance of the overland Silk Road, and the Sogdians’ unique role faded into history.

Though their name may not be as famous as the Romans or the Han Chinese, the Sogdians were the essential gear in the great machine of the Silk Road. They were the world’s great connectors, the circulatory system that pumped not just goods, but beliefs, art, and knowledge across the vast body of the Eurasian continent, shaping the world in ways we are still uncovering today.