Imagine a tomb, sealed not by stone and curses, but by the biting, eternal cold of the Siberian frontier. A tomb so perfectly frozen that it preserves not only the shimmer of gold but the very skin, hair, and even the last meals of people who lived over 2,500 years ago. These are not fantasies from a fiction novel; they are the Scythian kurgans of the Altai Mountains, nature’s own cryo-chambers that provide an unparalleled window into a lost world.

Who Were the Scythian Horse-Lords?

Before we venture into the ice, we must first meet the people who lie within. The Scythians were a nomadic people who dominated the vast Eurasian steppe from roughly the 9th to the 2nd century BCE. To settled civilizations like the Greeks and Persians, they were the stuff of legend and fear—fierce, horse-mounted archers who seemed to emerge from the endless grasslands, fight with terrifying skill, and vanish just as quickly. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote of them with a mixture of awe and revulsion, describing their nomadic lifestyle, their martial prowess, and what he considered their “barbaric” customs.

For centuries, these external accounts were all we had. The Scythians left behind no cities and no written records of their own. Their story was told by their enemies. But in the high peaks of the Altai Mountains, where Russia, China, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia converge, archaeology has allowed the Scythians to finally speak for themselves.

The Kurgans: Monuments on the Steppe

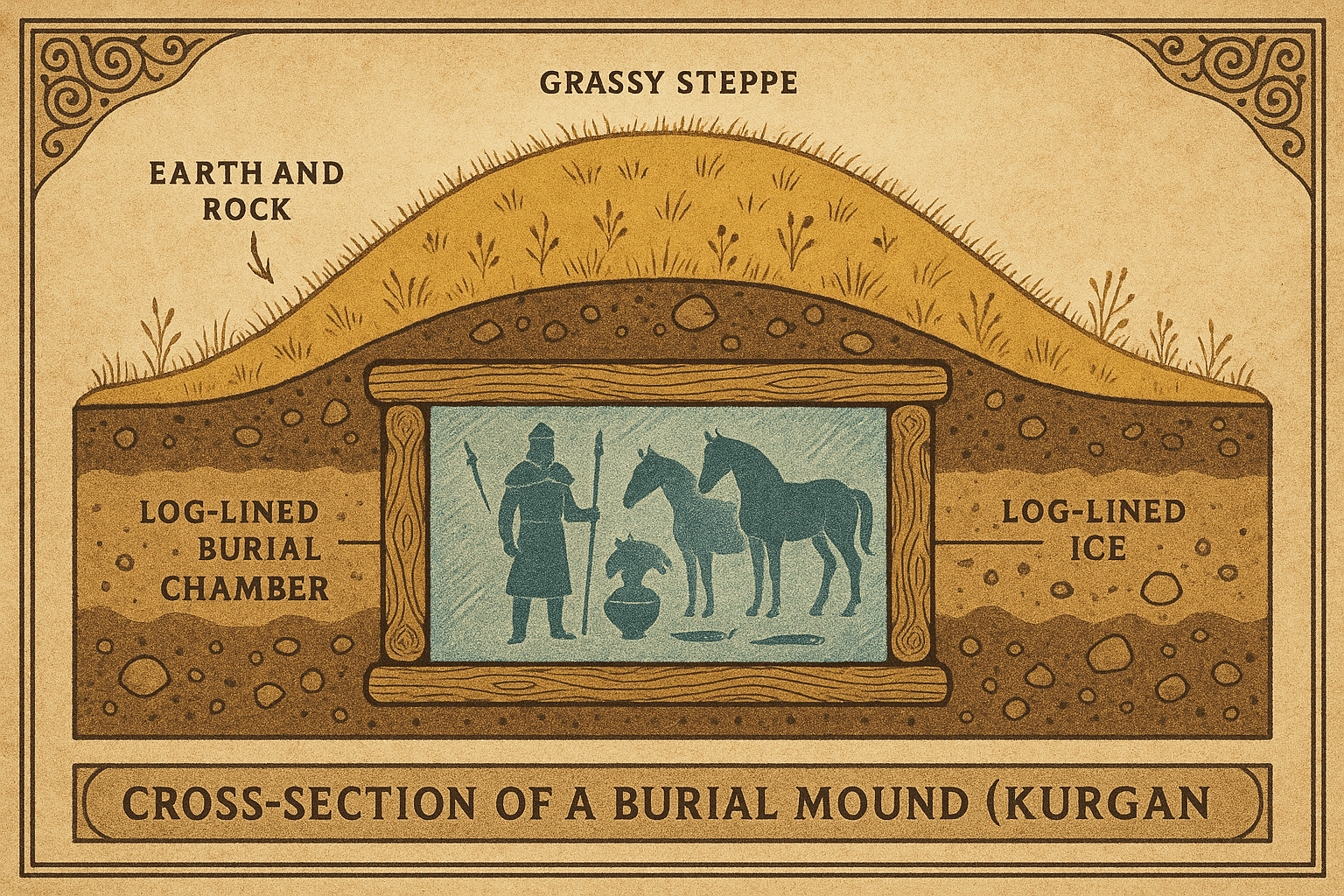

Across the steppe, the most visible legacy of the Scythians are their kurgans—earthen burial mounds that punctuate the landscape. These were not simple graves. A kurgan was a monumental undertaking, a statement of power and a sacred link between the living, the dead, and the cosmos. The deceased, typically a high-status individual like a chieftain or priestess, would be interred in a deep timber-lined chamber.

This chamber was a home for the afterlife, furnished with everything the deceased might need. After the funeral rites were complete, the chamber was roofed with logs and sealed. Above it, a massive mound of earth and stone was raised, creating a permanent landmark on the horizon. It is the unique combination of this architecture and the Altai’s climate that led to an archaeological miracle.

Nature’s Cryo-Chamber: The Miracle of the Permafrost

When the Scythians constructed these kurgans in the high Altai valleys, they inadvertently created perfect time capsules. Water seeped through the porous mound and into the sealed burial chamber below. In this high-altitude environment, the ground is in a state of permafrost. The water that entered the tomb quickly froze solid, encasing the chieftain, their attendants, and all their grave goods in a block of ice.

The great earthen mound above acted as a giant insulator, protecting the frozen core from the brief warmth of the summer months. While grave robbers, both ancient and modern, often tunneled into the kurgans to steal precious metals, they rarely disturbed the entire frozen context. What they left behind—the organic materials they deemed worthless—has become priceless to historians.

Treasures From the Ice: More Than Just Gold

The discoveries made in the frozen kurgans, particularly the famous Pazyryk burials, have revolutionized our understanding of Scythian culture. While the goldwork is stunning, confirming their mastery of the iconic “Animal Style” art, it is the perishable items that truly tell the story.

The “Siberian Ice Maiden” and Her Tattoos

Perhaps the most famous discovery is the “Princess of Ukok”, a 25-year-old woman unearthed in the 1990s. Buried with six horses, she was clearly a person of high status, possibly a revered priestess. But the most astonishing feature was her skin. Perfectly preserved by the ice, her shoulders, arms, and hands were covered in intricate tattoos depicting mythical creatures, including a deer with a griffin’s beak. These were not crude markings but sophisticated works of art that spoke of identity, status, and spiritual belief. They proved that tattooing was a high art form, challenging the long-held association of tattoos with lower social classes in the ancient world.

The World’s Oldest Carpet and Intricate Textiles

Among the ice-bound artifacts of the fifth Pazyryk kurgan was a textile of breathtaking beauty and importance: the Pazyryk Carpet. Dating to the 5th century BCE, it is the oldest known pile carpet in the world. Its weave is dense and its patterns—a procession of deer, griffins, and horsemen—are incredibly detailed. Its artistry suggests a highly sophisticated weaving tradition, while its stylistic similarities to Persian art hint at the vast cultural and trade networks the Scythians were part of. Alongside it were vibrant felt wall hangings, Chinese silk (proving a “Silk Road” existed long before it was formally named), and clothing made of fur and finely woven wool.

Chariots, Horses, and the Afterlife

The horse was central to Scythian life, and this is vividly reflected in the kurgans. Elite individuals were buried with their favorite mounts, which were sacrificed and interred with them. These horses were not just thrown in; they were adorned with elaborate bridles, saddles, and fantastical masks that transformed them into mythical beasts for the journey to the next world. Even more surprisingly, archaeologists found entire wooden chariots. These large vehicles were carefully disassembled to fit into the burial chambers, indicating they were crucial ceremonial objects, perhaps used in funeral processions, rather than tools of war.

Rewriting the Narrative of the “Barbarian”

The contents of the ice tombs paint a picture far removed from the one-dimensional “barbarian” described by Herodotus. The Scythians of the Altai were a people of immense sophistication.

- Their art was not just decorative but deeply symbolic, encoding a complex mythology on everything from gold plaques to human skin.

- They possessed advanced technology in everything from weaving to woodworking.

- They were key players in a transcontinental network of exchange, trading with Persia, China, and the Greek world.

- Their spiritual life was rich, with elaborate beliefs about the afterlife that demanded immense resources and ritual preparation.

Today, these incredible sites are under threat. Climate change is causing the permafrost to thaw at an alarming rate, risking the destruction of any remaining kurgans and their fragile contents. The race is on to discover and preserve these frozen echoes of the past before they melt away, taking the true story of the Scythian horse-lords with them.