From 224 to 651 AD, the Sassanian Empire was the other superpower of the ancient world. It was a realm of immense wealth, sophisticated culture, and formidable military might, ruled by a line of emperors who called themselves the Shahanshah, or “King of Kings.” This was not a barbarian horde at the gates; this was a clash of civilizations, a titanic struggle between two empires that saw themselves as the rightful rulers of the world.

The Rise of a New Persian Dynasty

The story begins with the decline of the Parthian Empire, which had ruled Persia for centuries. The Parthians were a decentralized, feudal kingdom, and by the early 3rd century AD, their power was waning. In the province of Persis (modern Fars), the historical heartland of the ancient Achaemenid Persians, a local priest and governor named Ardashir I rose in rebellion.

Ardashir was ambitious and charismatic. He claimed descent from the legendary Achaemenid kings like Cyrus and Darius the Great, positioning himself as the restorer of Persian glory. In 224 AD, at the Battle of Hormozdgan, Ardashir decisively defeated the last Parthian king, Artabanus V. He then marched to the capital, Ctesiphon, and was crowned Shahanshah, inaugurating a new dynasty that would bear the name of his ancestor, Sasan.

Unlike the Parthians, Ardashir built a highly centralized state. He established Zoroastrianism as the state religion, using its powerful priesthood (the Magi) to unify his diverse realm under the concept of Iranshahr, the “Domain of the Aryans.” This new, aggressive, and ideologically unified Persia immediately came into conflict with its great western neighbor: Rome.

A Clash of Superpowers: The Roman-Sassanian Wars

The Roman-Sassanian wars were some of the longest and most destructive conflicts in human history. For 400 years, the border along the Euphrates River was a near-constant warzone. These were not mere border skirmishes; they were existential struggles for dominance.

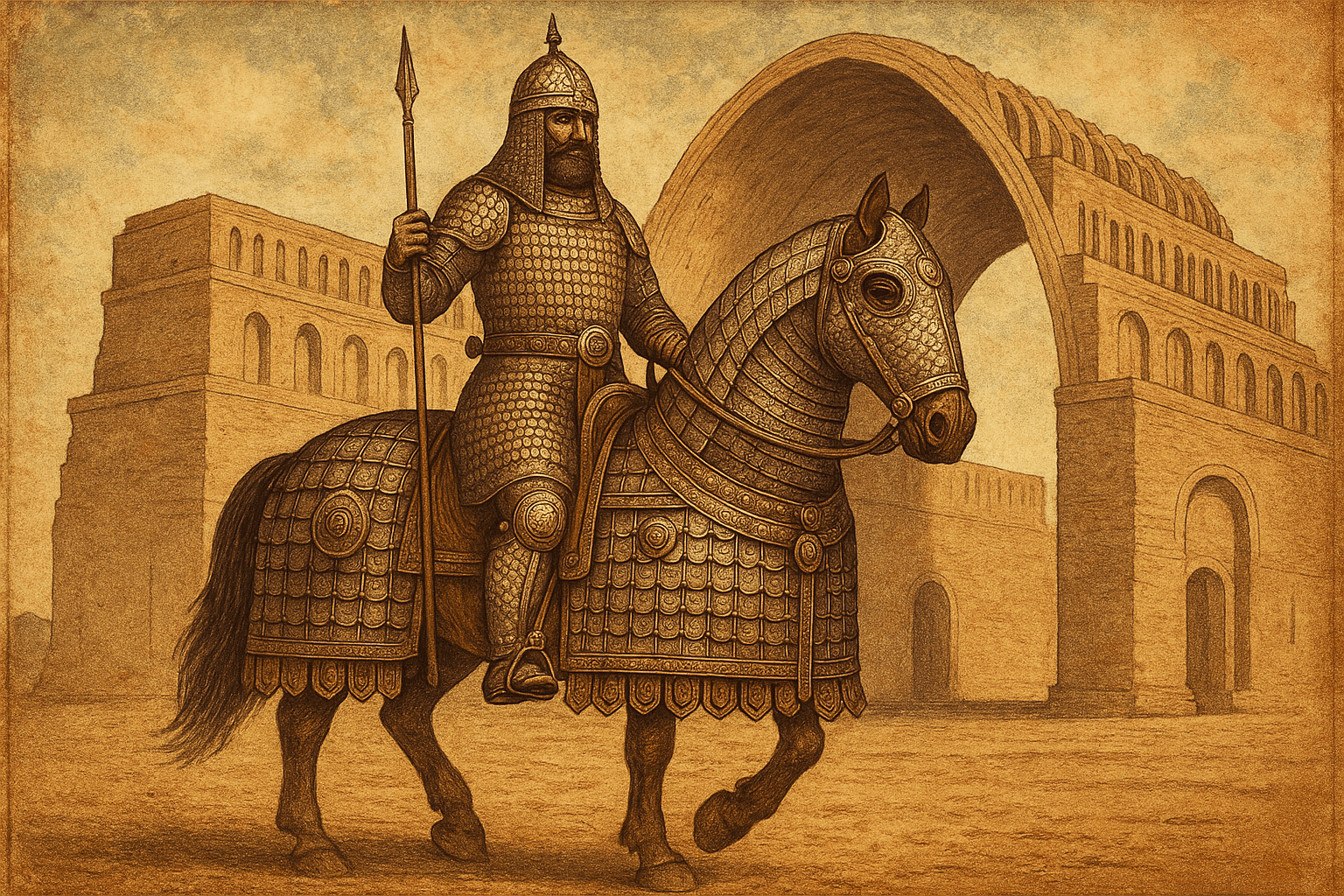

One of the most stunning moments came under Ardashir’s son, Shapur I. In 260 AD, during a major battle near Edessa, Shapur achieved the unthinkable: he defeated a massive Roman army and captured the Roman Emperor Valerian himself. Valerian became a prisoner for the rest of his life, a humiliation Rome would never forget. The event was immortalized in massive, triumphal rock reliefs at Naqsh-e Rustam in Iran, showing the Roman emperor kneeling before the mounted Shahanshah—one of the most potent pieces of political propaganda ever created.

The pendulum swung back and forth. A century later, in 363 AD, the ambitious Roman Emperor Julian “the Apostate” launched a massive invasion of Persia, hoping to end the Sassanian threat for good. He reached the walls of the capital, Ctesiphon, but was outmaneuvered and killed in a skirmish. His army was forced into a humiliating retreat and had to cede significant territory to the Sassanians just to escape annihilation.

The final and most devastating act of this long drama was the Byzantine-Sassanian War of 602–628. Spurred by revenge, the Shahanshah Khosrow II launched an invasion that nearly destroyed the Byzantine Empire. Sassanian armies conquered Syria, Palestine, and Egypt, and in 626, they laid siege to Constantinople itself alongside their Avar allies. But in a brilliant counter-offensive, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius took the war deep into Persia, leading to Khosrow’s overthrow and a peace treaty that restored the old borders. It was a Pyrrhic victory. Both empires were left utterly exhausted, financially ruined, and militarily depleted.

Inside the Empire of the Shahanshahs

Beyond the battlefield, the Sassanian Empire was a complex and vibrant civilization. Society was organized into a rigid caste system: priests, warriors, scribes, and commoners. At the pinnacle was the Shahanshah, an absolute monarch whose authority was believed to be granted by the supreme Zoroastrian god, Ahura Mazda.

Zoroastrianism was the empire’s ideological glue. This ancient religion posited a cosmic struggle between the forces of good and light (led by Ahura Mazda) and evil and darkness (led by Ahriman). Sacred fires, tended by priests in fire temples, burned eternally as a symbol of purity and the divine presence. While Zoroastrianism was the state faith, the empire was also home to large and ancient communities of Jews and various Christian denominations. Their treatment varied from tolerance to brutal persecution, often depending on the political climate and whether they were seen as a fifth column for Christian Rome.

A Golden Age of Culture and Science

The Sassanian period was a golden age for Persian culture. Their art and architecture were magnificent, characterized by opulent silver-gilt plates depicting royal hunts, intricate stucco reliefs, and colossal structures. The most famous ruin is the Taq-i Kasra in Ctesiphon, which still boasts the largest single-span brick arch in the world—a testament to their engineering genius.

Perhaps their most enduring contribution was in the realm of knowledge. The Academy of Gondishapur, in southwest Iran, became one of the most important intellectual centers of the late ancient world. When the Byzantine Emperor Justinian closed the School of Athens in 529 AD, its pagan philosophers found refuge at Gondishapur. There, Greek philosophers, Jewish scholars, Nestorian Christian physicians, and Indian mathematicians came together under royal patronage. They translated and synthesized medical and scientific texts from Greek, Syriac, and Sanskrit, preserving ancient knowledge and making new discoveries. It was through Sassanian Persia that many Indian concepts, including the game of chess and the numerals that would become our “Arabic numerals”, journeyed westward.

The Unexpected Fall and Lasting Legacy

The final, apocalyptic war between Heraclius and Khosrow II left a power vacuum. Both empires were broken shells of their former selves, ripe for a new, unforeseen force. Erupting from the Arabian Peninsula, Arab armies united by the new faith of Islam fell upon the weakened giants.

The exhausted Sassanian Empire, plagued by internal strife following the war, could not mount an effective defense. At the decisive Battle of al-Qadisiyyah in 636 AD and the Battle of Nahavand in 642 AD (“the Victory of Victories”), the Sassanian army was shattered. The last Shahanshah, Yazdegerd III, became a fugitive in his own land and was assassinated in 651, bringing 400 years of Sassanian rule to an end.

But the empire did not simply vanish. Its legacy was profound. The new Arab Caliphates, particularly the Abbasids, heavily modeled their courts, administration, and traditions of kingship on Sassanian practices. Persian became the language of literature and high culture in the Islamic world for centuries. The cultural identity of “Iran” had been so deeply forged by the Sassanians that it survived the conquest and the conversion to Islam, creating the unique synthesis that is modern Persian culture.

The Sassanian Empire is a critical, often-overlooked chapter of world history. It was the bridge between ancient Persia and the Islamic world, the superpower that stood equal to Rome, and a civilization whose ideas, art, and legacy helped shape the world long after its great fire temples had gone cold.