The Sasanian Empire (224-651 AD) was a powerhouse of the ancient world, a rival to Rome and later Byzantium, stretching from Mesopotamia to the fringes of India. While they left behind monumental rock reliefs and impressive architecture, it is their portable art, particularly their magnificent silverwork, that provides one of the most intimate glimpses into their imperial ideology.

A Glimpse into the Royal Treasury

Sasanian silver plates were not for serving dinner. They were luxury objects of the highest order, reserved for the royal court and the highest echelons of the aristocracy. Crafted from high-purity silver, they were often decorated using a combination of sophisticated techniques:

- Repoussé: Hammering the design into the plate from the reverse side to create a raised relief.

– Chasing: Refining and adding detail to the design from the front with specialized tools.

– Gilding: Applying a thin layer of gold, often using a mercury amalgam process, to highlight key figures and details, especially the king.

– Inlay: Adding niello, a black metallic alloy, to create contrast and define lines.

These plates served multiple functions. They were symbols of immense wealth and status, displayed at court to impress visitors. They were also crucial diplomatic gifts, sent to foreign rulers and tribal leaders on the empire’s frontiers as a tangible representation of Sasanian magnificence and power. Their discovery in burial hoards as far away as the Ural Mountains in Russia attests to their value as prestige goods across a vast network of trade and diplomacy.

The King as the Hero: Symbolism in Action

The scenes depicted on these plates are a tightly controlled set of themes designed to project a very specific image of the monarch. The Sasanian ruler was not merely a political leader; he was the Shahanshah (King of Kings) and the earthly guarantor of divine order.

The Royal Hunt

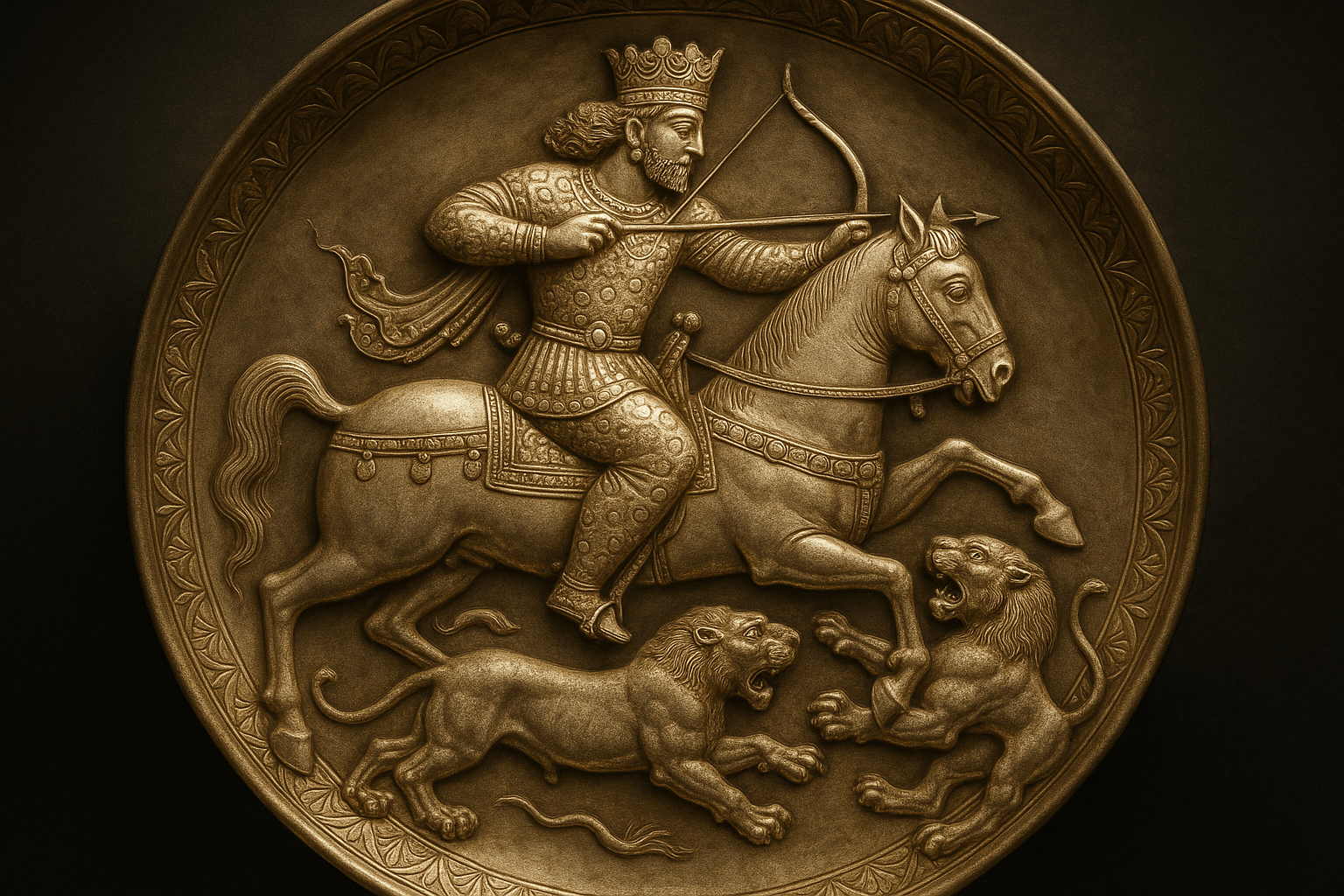

The most iconic and frequently depicted scene is the royal hunt. On a famous plate attributed to Shapur II (r. 309-379 AD), the king is shown on horseback coolly dispatching two stags with a single arrow. On others, kings like Khosrow II (r. 590-628 AD) single-handedly take on powerful beasts like lions and boars. These are not simple sporting scenes.

In Zoroastrian cosmology, which heavily influenced Sasanian thought, the world was a battleground between order (asha) and chaos (druj). Wild, dangerous animals like boars and lions were physical manifestations of this chaotic principle. The king, by hunting and effortlessly defeating them, was symbolically reenacting his divine duty to vanquish chaos and maintain order in the cosmos. His serene expression and flawless posture amidst the violent struggle emphasized that his victory was preordained, a result of his divine grace, known as khvarenah.

The Enthroned King and Courtly Life

Another key theme is the king enthroned, sometimes holding an audience or presiding over a banquet. These scenes are formal, static, and rigidly hierarchical. The king is always the central and largest figure, seated frontally on a magnificent throne, a picture of absolute, unshakeable authority. He is surrounded by smaller, often identical-looking court attendants, their positions relative to the king signifying their rank. These plates were a visual representation of the Sasanian state itself: a perfectly ordered universe with the King of Kings at its undisputed center.

The Artistry of Power

The artistic style of the plates was just as important as the subject matter in conveying the imperial message. Sasanian artists developed a unique visual language to deify their ruler.

The most critical element was the king’s crown. Each Sasanian king wore a unique and elaborate crown, a design which was his alone. This practice allows historians to identify the king and accurately date many of the plates. More than just a hat, the crown was the primary symbol of his legitimacy and divine connection.

Another key feature is the fluttering ribbons (pativ) that flow from the king’s crown, his shoulders, and even the harnesses of his horse. These ribbons were the visual manifestation of the khvarenah—that divine glory and fortune bestowed by the gods that legitimized his rule. The king is literally radiating divine grace. The combination of the unique crown, the king’s calm demeanor, and the flowing ribbons created an unmistakable icon of a divinely sanctioned ruler.

A Legacy in Silver

When the Sasanian Empire fell to the Arab conquests in the mid-7th century, its political power vanished, but its cultural influence endured. The new Islamic Caliphates, particularly the Abbasids, were deeply influenced by Persian courtly traditions. The imagery of the royal hunt and the enthroned ruler continued to be a potent symbol of power for centuries.

The Sasanian silver plates, therefore, are far more than just beautiful artifacts. They are a masterclass in political branding. Each gilded figure and hammered detail was part of a sophisticated visual program to communicate a clear message: the Sasanian king was the center of the world, the protector of order, and the chosen vessel of the divine. They are a shining testament to an empire that understood that an image, crafted in eternal silver and gold, could be just as powerful as an army.