The First Law of the Land

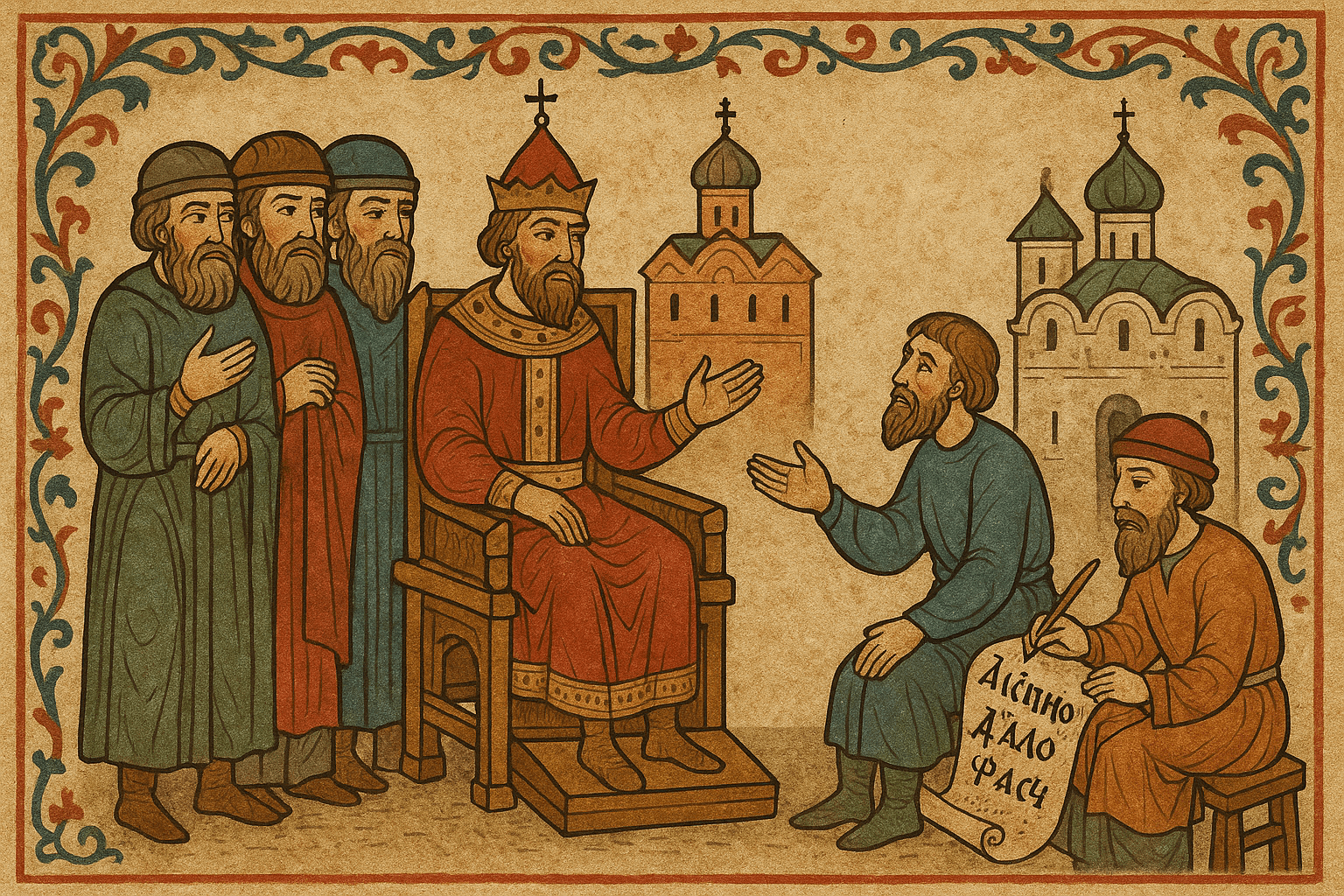

The Russkaya Pravda isn’t a single book of law handed down from on high. Instead, it’s a living document, a compilation of statutes, judicial precedents, and customary laws collected and amended over several generations. Its origins are traditionally linked to the great rule of Yaroslav the Wise (c. 978-1054), a grand prince who oversaw a golden age in Kievan Rus’.

The earliest version, known as the Short Pravda, dates to Yaroslav’s time and is refreshingly direct. It was later expanded upon by his sons, creating the Expanded Pravda, which addressed the needs of a more complex and stratified society. Unlike the Roman-inspired law that dominated Western Europe, the Russkaya Pravda grew from native Slavic and Scandinavian traditions, reflecting the Viking (or Varangian) origins of the Kievan Rus’ ruling dynasty.

A Price for Everything: The Vira System

The most striking feature of the Russkaya Pravda is its near-total avoidance of capital and physical punishment for most crimes. While medieval Europe was replete with hanging, beheading, and mutilation, the Rus’ primarily relied on a system of fines. At the heart of this was the vira, a blood-fine paid to the prince for the murder of a free man.

This wasn’t about letting a killer buy his freedom in the modern sense. It was a state-regulated mechanism to prevent the endless cycle of blood feuds between clans. Instead of seeking personal revenge, the victim’s family was compensated for their loss, and the prince’s treasury was enriched for the disruption to social order. The system was meticulously detailed:

If a man kills a man, the brother is to avenge the brother, or the son the father, or the cousin, or the nephew; if no one is to avenge him, then 40 grivnas for the head.

— Russkaya Pravda (an excerpt illustrating the transition from blood feud to vira)

The amount of the vira was not uniform; it was a direct reflection of the victim’s social standing. This is where the code becomes a mirror, revealing the deeply hierarchical nature of Kievan society.

A Mirror to Society: Social Hierarchy in the Code

By studying the fines, we can reconstruct the social ladder of the Kievan Rus’. The life of every person had a price, and that price told you exactly where they stood.

- The Elite: At the top were the prince’s inner circle—his military retainers (druzhina) and high-ranking officials (knyazhiy muzh). The vira for killing one of them was a “double vira” of 80 grivnas, an enormous sum that highlighted their importance to the state.

- The Freemen: The standard vira of 40 grivnas was set for an ordinary free man (lyudin). This category included merchants, artisans, and land-owning peasants who formed the backbone of Rus’ society. Interestingly, the life of a free woman was valued at a “half-vira” of 20 grivnas.

- The Dependent Classes: Lower on the scale were people like the smerdy (state peasants) and zakupy (individuals working off a debt). Their lives were valued at a mere 5 grivnas, as their death was primarily an economic loss to their lord or creditor.

- The Slaves: At the very bottom were the slaves (kholopy). As property, they had no vira. Killing a slave was not legally considered murder; it was property damage. The owner was compensated for their economic loss, typically 5 grivnas for a male slave and 6 for a female slave (likely due to her reproductive value).

This stratified system demonstrates a society that was pragmatic and deeply concerned with status. Justice was not blind; it was keenly aware of who you were.

Beyond Murder: Regulating Daily Life and Honor

The Russkaya Pravda governed far more than just homicide. It was a comprehensive guide to navigating daily life and commerce, providing a rich tapestry of societal values.

Property was paramount. There were specific fines for stealing horses (a crucial military and agricultural asset), boats, and even beehives, reflecting the importance of beekeeping for honey and wax. If a thief was caught and killed in the act of nighttime robbery, it was not considered a crime—a rare exception to the fine-based system.

Honor was tangible. One of the most telling laws concerned personal insults. The act of pulling a man’s beard or moustache was a grave offense, seen as a direct attack on his honor and virility. The fine for this public humiliation was a steep 12 grivnas—the same as the fine for cutting off a finger!

The code also laid out legal procedures. While it relied on witnesses (vidoki), it also employed trial by ordeal, a common medieval practice. To prove their innocence, an accused party might be forced to carry a piece of hot iron or be dunked in water. Divine judgment, it was believed, would protect the innocent from harm.

The Enduring Legacy

The Russkaya Pravda remained the foundational legal text for East Slavic principalities for centuries, influencing the legal codes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and, later, Muscovy. When it was eventually superseded by more centralized and punitive legal systems in the 15th and 16th centuries, the age of the vira came to a close, replaced by the state’s monopoly on corporal and capital punishment.

Today, the Russkaya Pravda is more than just a dusty legal document. It is a vital historical source that allows us to look past the grand narratives of princes and battles and see the inner workings of a medieval civilization. It shows us a society grappling with the balance between revenge and order, status and justice, and a world where law was less about abstract morality and more about restoring a fragile social harmony, one fine at a time.