In the bustling, mud-caked streets of 12th-century Europe, a quiet revolution was taking place. This wasn’t a war fought with swords and shields, but one waged with books, ideas, and fierce debate. Amidst the rising spires of new cathedrals and the growing hum of urban commerce, a new kind of institution was clawing its way into existence: the university. Far from being a sudden invention, the university was the culmination of centuries of intellectual preservation and a direct response to a continent awakening from a long slumber. It was here, in the lecture halls of Bologna, Paris, and Oxford, that the foundations of the Western intellectual tradition were laid.

From Cloister to Cathedral Square

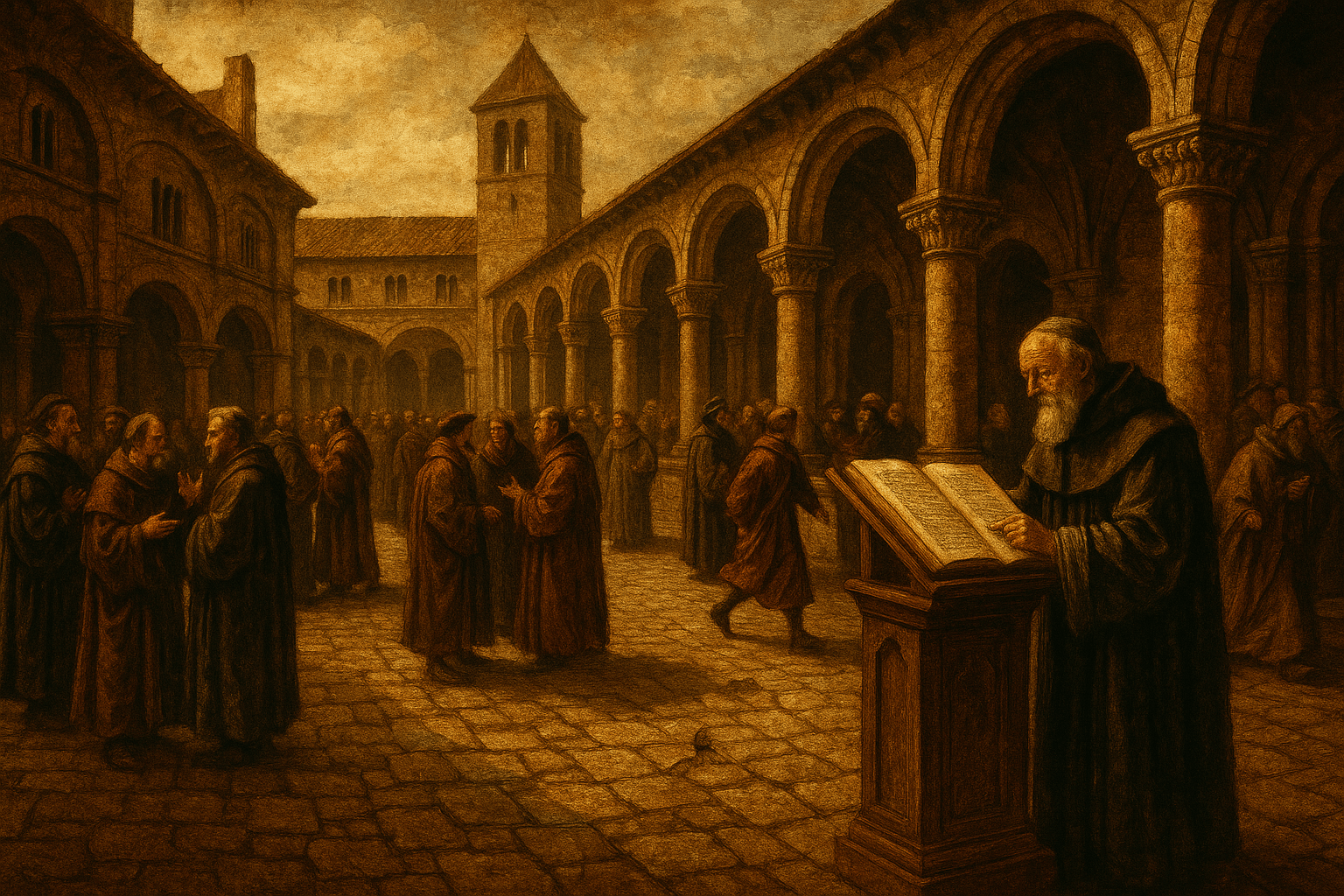

For centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, the flickering flame of classical learning was kept alive primarily within the stone walls of monasteries. Monks, particularly of the Benedictine order, painstakingly copied manuscripts, preserving works of philosophy, science, and literature that would have otherwise been lost. These monastic schools, however, were largely inward-facing, designed to train novices for a life of religious devotion. Their purpose was preservation, not innovation.

The real shift began around the 11th century with the rise of the cathedral schools. As Europe’s population grew and towns swelled into cities, cathedrals replaced monasteries as the centers of religious and, increasingly, intellectual life. Attached to major cathedrals like Notre Dame in Paris and Chartres, these schools were created to train secular clergy—the priests and administrators who served the growing populace. Unlike their monastic counterparts, they were located in vibrant urban centers, attracting ambitious young men not just from the clergy but also from the growing ranks of the laity who sought knowledge and career advancement.

These schools became magnets for renowned masters, whose fame could draw students from across the continent. This created a volatile, dynamic environment—a critical mass of scholars and students hungry for more than what the traditional curriculum could offer.

The Birth of the Universitas

The final catalyst for the university’s birth was a perfect storm of social and intellectual developments. A more stable political climate and renewed trade routes, especially with the Byzantine and Islamic worlds, led to a flood of new—or rather, rediscovered—knowledge pouring into Europe. Works of Aristotle, advanced medical texts from Arabic physicians like Avicenna, and, most crucially, a complete copy of Justinian’s Corpus Juris Civilis (a compilation of Roman law) were translated into Latin.

This explosion of information overwhelmed the old cathedral school structure. A single master could no longer teach everything. Specialized knowledge demanded specialized teachers. In response, scholars and students began to band together to protect their own interests, forming guilds in the same way that stonemasons or weavers did. This guild was called a universitas, a Latin term meaning “a whole” or “a corporation.” Initially, the term had nothing to do with a physical place of learning; it was a legal entity, a guild of masters and/or students.

The universitas gave them the collective power to negotiate with local authorities—both town officials and bishops—for rights, privileges, and, most importantly, autonomy. This legal “charter” is what formally distinguished a university from its cathedral school predecessors. Two dominant models for this new institution quickly emerged.

The Bologna Model: A Student-Run Corporation

The first true university is widely considered to be the University of Bologna in Italy, which emerged in the late 11th century. Its origin story is a fascinating tale of consumer power. Bologna was the center for the study of Roman Law, attracting mature students from across Europe who were often already men of some standing in their home communities.

These students organized themselves into a powerful universitas scholarium (a guild of students). In this model:

- The students hired the professors directly.

- They paid the professors’ salaries and could collectively fire them for poor performance.

- Students fined professors for being late, for failing to cover the entire curriculum, or for skipping over difficult passages in a text.

This student-led model, focused on the practical and lucrative study of law, became the blueprint for most universities in southern Europe, including those in Spain, Portugal, and other parts of Italy.

The Paris Model: A Guild of Masters

In northern Europe, a different model took shape. The University of Paris grew out of the renowned cathedral school of Notre Dame and its cluster of famous teachers, including the celebrated and controversial Peter Abelard. Here, it was the masters who formed a guild, the universitas magistrorum (a guild of masters), to protect themselves from the meddling of the local bishop and chancellor of the cathedral.

In 1231, after a violent clash between students and city authorities led the masters to suspend lectures for two years (an academic strike!), Pope Gregory IX issued the bull Parens Scientiarum (“Mother of Sciences”). This document is often considered the Magna Carta of universities, as it granted the University of Paris the right to self-governance, control its own curriculum, and issue its own degrees, largely free from local episcopal control. This master-led model, with its strong focus on theology and philosophy, became the standard for northern universities, most famously for the University of Oxford, which itself was formed by English masters who left Paris after a dispute in 1167.

Life at a Medieval University

What was it like to be a student in the 13th century? Imagine a young man, perhaps only 14 or 15, traveling hundreds of miles to a foreign city. He would find lodging in a rented room, surrounded by boisterous colleagues from different lands. Classes were held in hired halls, with students sitting on straw-covered floors while a master, robed and seated, read from a rare, precious manuscript.

The core of the curriculum was the Seven Liberal Arts, divided into:

- The Trivium: Grammar, rhetoric, and logic—the arts of language and argument.

- The Quadrivium: Arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—the arts of number and quantity.

After completing a Bachelor of Arts, a student could move on to the higher faculties: Law, Medicine, or the most prestigious of all, Theology, the “Queen of the Sciences.” The primary teaching methods were the lectio (lecture) and the disputatio (disputation), a formal, structured debate where students and masters would test their logical and rhetorical prowess on complex questions. This system of formal study, progressive degrees, and academic debate is the direct ancestor of the university system we know today.

An Enduring Legacy

The rise of the medieval university was a pivotal moment in world history. These institutions were not just centers of learning; they were powerful, self-governing corporations that created a pan-European intellectual community. By standardizing curricula and degrees, they ensured that a scholar from Oxford could be understood in Bologna or Salamanca. They championed a new way of thinking, grounded in logic and rigorous inquiry, that would fuel the Renaissance, the Scientific Revolution, and the Enlightenment. When you walk onto a modern university campus, you are stepping into an institution with a nearly thousand-year-old legacy, born in the dynamic and intellectually fervent world of the High Middle Ages.