A City Born from Refugees

Ragusa’s story begins in the 7th century, amidst the twilight of the Roman Empire. As Slavic tribes pushed into the Balkans, Romanized citizens from the nearby city of Epidaurum (modern-day Cavtat) fled for their lives. They found refuge on a small, rocky island just off the coast, which they named Laus. Across a narrow, marshy channel, a Slavic settlement known as Dubrava (meaning “oak grove”) began to grow. For centuries, these two communities existed side-by-side, one Latin and maritime, the other Slavic and agrarian.

In the 12th century, the channel between them was filled in, creating the magnificent main street we know today as the Stradun. This physical union symbolized the merging of two cultures, creating a unique Slavo-Roman identity that would become one of Ragusa’s greatest strengths. Perched on the edge of empires, it learned early on that survival depended on balancing its heritage and playing all sides.

Navigating the Great Powers: From Byzantium to Venice

Initially, Ragusa operated under the protection of the Byzantine Empire, enjoying considerable autonomy while benefiting from the security of a distant overlord. However, the Fourth Crusade in 1204 shattered the old order. Venice, hungry for control of Adriatic trade routes, emerged as the dominant regional power. From 1205 to 1358, Ragusa fell under Venetian suzerainty.

While often described as a rivalry, this period was more complex. Venice did not rule Ragusa directly but controlled its foreign policy and skimmed profits from its trade. Internally, Ragusa’s noble families continued to manage their own affairs, learning valuable lessons in governance and maritime commerce from their Venetian overlords. The lion of St. Mark, Venice’s symbol, may have flown from the ramparts, but within the walls, the spirit of Ragusan independence was biding its time.

That time came in 1358. With the Treaty of Zadar, Venice was forced to cede its Dalmatian territories to the powerful Kingdom of Hungary. Ragusa skillfully negotiated its new position, agreeing to pay a symbolic tribute to the Hungarian-Croatian king in exchange for complete self-governance. It was now a de facto independent republic, free from Venetian dominance and ready to chart its own course.

The Art of the Deal: The Ottoman Connection

As the Republic of Ragusa entered its golden age, a new, formidable power was rising to the east: the Ottoman Empire. While Venice and other Christian powers engaged in costly and bloody wars against the Sultan, Ragusa chose a radically different path—diplomacy.

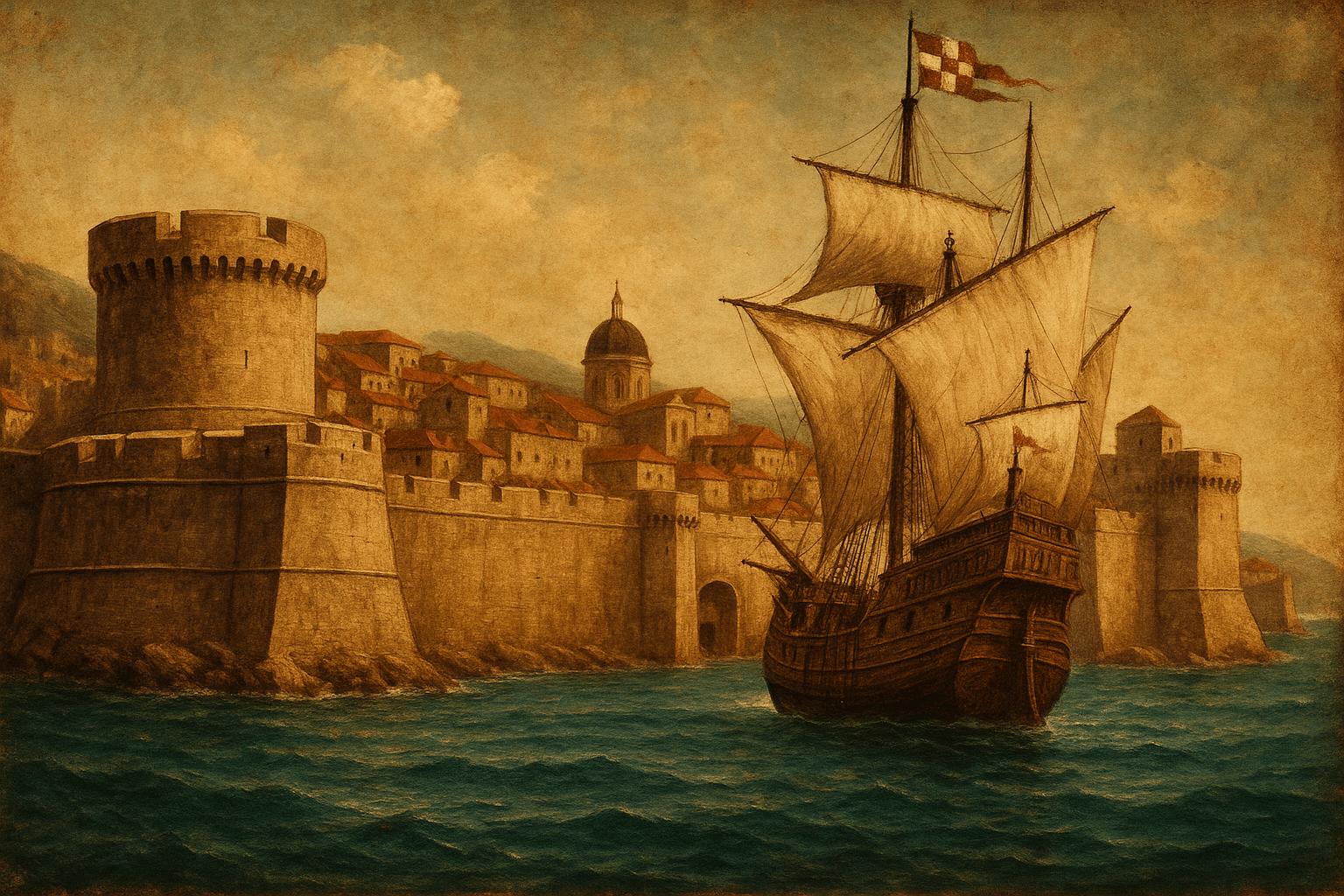

In a masterstroke of political calculation, Ragusa voluntarily became a tributary vassal of the Ottoman Empire. By paying a substantial annual tribute (the harač), its merchants were granted something priceless: privileged and near-exclusive access to trade routes deep within the Ottoman-controlled Balkans. Ragusan caravans could travel safely where Venetian or Genoese traders dared not go, bringing back silver, leather, and wool to be shipped across the Mediterranean from their bustling port.

This arrangement was pure pragmatism. The tribute was, in essence, an insurance policy and a business fee. It secured Ragusa’s landward borders and allowed it to remain neutral in the devastating wars between Venice and the Ottomans. While Venetian galleys fought Ottoman fleets, Ragusan merchant ships sailed peacefully, their hulls filled with profitable cargo. The Ragusans became the indispensable middlemen, serving as the West’s window into the Ottoman world and vice versa.

“LIBERTAS”: The Republic in its Golden Age

Freed from external threats, Ragusa focused on perfecting its internal society during the 15th and 16th centuries. It was an aristocratic republic governed by a rigid class structure of nobles, commoners, and clergy. Power was carefully distributed to prevent any one individual or family from becoming too powerful.

- The Rector (Knez): The head of state was elected for a term of only one month and was confined to the Rector’s Palace during that time, to focus solely on the affairs of the Republic.

- The Councils: Power was divided between the Great Council (all male nobles over 18), the Senate (45 experienced members who set policy), and the Small Council (an executive body).

This stable government fostered a society that was remarkably progressive for its time. Ragusa was at the forefront of social innovation:

- In 1377, it established Europe’s first quarantine system (the lazarettos) to protect against the plague.

- In 1416, it became one of the first states in Europe to formally abolish the slave trade, declaring it “shameful, wrong, and disgusting.”

- It founded one of Europe’s oldest orphanages in 1432 and had a sophisticated public health and pharmacy system.

The word LIBERTAS (Liberty) was inscribed on its fortresses and coins, a constant reminder of the principle that guided the Republic. This was not just freedom from foreign rule, but a commitment to justice, order, and rational governance.

The Earth Shakes and the Tides Turn

The beginning of the end for Ragusa came not from an invading army, but from the ground beneath it. In 1667, a catastrophic earthquake leveled much of the city, killing over 5,000 people, including the Rector. The city was painstakingly rebuilt in the stunning Baroque style we admire today, but the Republic never fully recovered its former wealth or demographic strength.

At the same time, the world was changing. The discovery of the Americas and new Atlantic trade routes shifted the center of global commerce away from the Mediterranean. Ragusa’s role as a key intermediary slowly diminished.

The final blow came with Napoleon Bonaparte. Preaching liberty while bent on conquest, his army entered the city under false pretenses in 1806, claiming they were only passing through. Two years later, in 1808, Marshal Marmont officially dissolved the Republic of Ragusa, extinguishing a flame that had burned brightly for centuries. The motto of “Liberty” was finally silenced.

Today, as millions of visitors walk the walls of Dubrovnik, they are treading on the legacy of a state that mastered the delicate art of survival. Ragusa is a testament to the idea that in a world of empires, a small nation can thrive not with the sword, but with wisdom, diplomacy, and an unshakable belief in its own freedom.