A Border Drawn in Confusion

Our story begins in 1441 in the heart of Renaissance Italy. The Papal States, led by Pope Eugene IV, were financially strained after a long conflict. To refill his coffers, the Pope agreed to sell the town of Borgo San Sepolcro and its surrounding territory to the powerful Republic of Florence for a sum of 25,000 gold florins. The treaty was signed, and all that remained was to mark the new border.

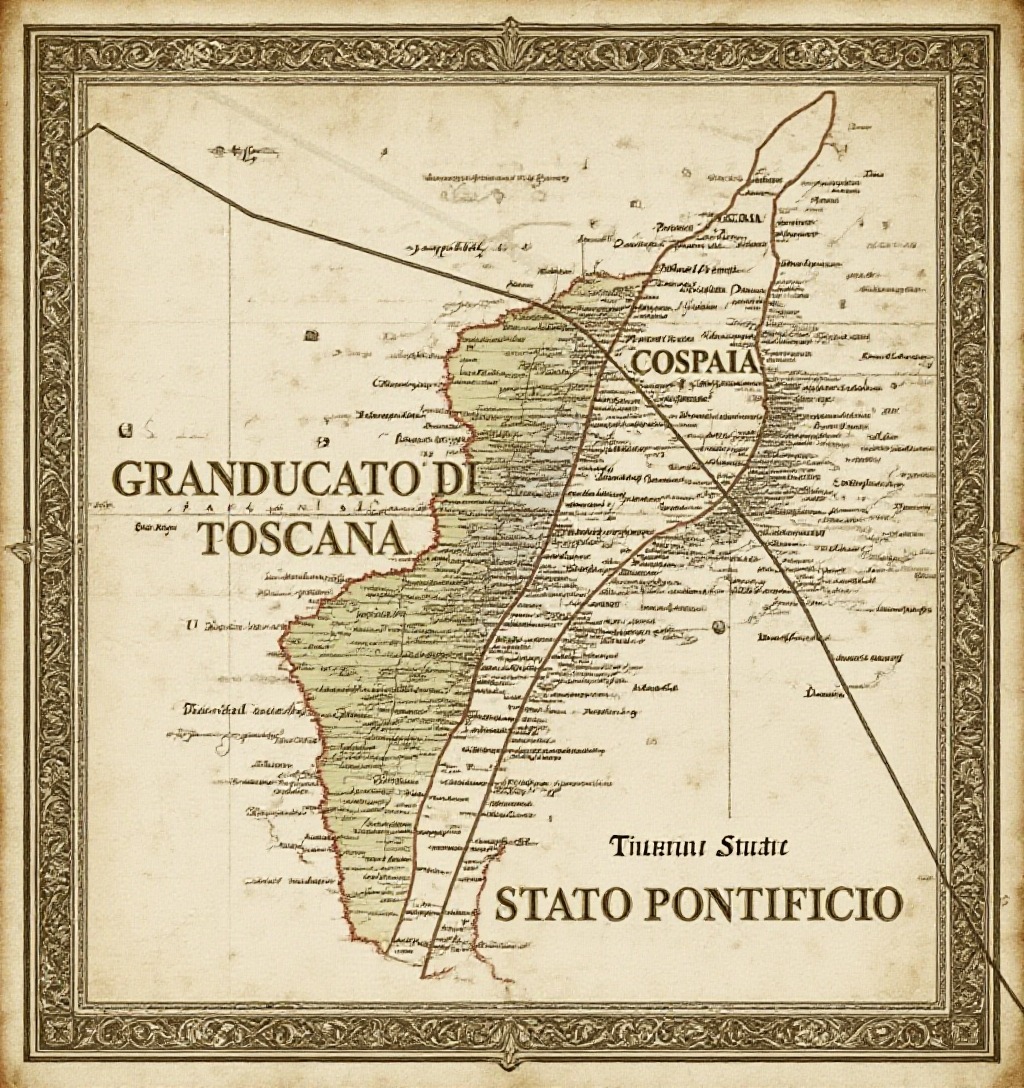

The treaty stipulated that the new boundary would follow a stream named “Rio.” Surveyors from both Florence and the Papal States set out to find this landmark. Here, a simple linguistic oversight turned into a geopolitical anomaly. “Rio” is simply the Italian word for “stream”, and as it happened, there were two different streams with this common name in the area.

The Florentine surveyors went to the northernmost stream, while the Papal surveyors went to one about 500 meters to the south. Each party marked their border and went home, satisfied they had done their job correctly. In doing so, they unknowingly created a narrow, unclaimed strip of land between the two new frontiers. This territory, about 2.5 kilometers long, technically belonged to neither Florence nor the Papal States. It was a sovereign void on the Italian peninsula.

The inhabitants of this tiny new no-man’s-land quickly realized their unique situation. They were no longer subjects of the Pope, nor were they citizens of Florence. Seeing a golden opportunity, they declared themselves an independent republic: the Republic of Cospaia.

Anarchy, Freedom, and a Tobacco Boom

For the next 385 years, Cospaia operated under a unique system that could best be described as organized anarchy. It had no formal government, no army, no police force, no prisons, and, most importantly, no taxes. The republic’s affairs were managed by a “Council of Elders and Heads of Families”, a loose governing body that met to resolve disputes and maintain a semblance of order. Their official motto neatly summed up their existence: Perpetua et firma libertas (“Perpetual and secure freedom”).

For its first century, Cospaia was little more than a historical curiosity. But in the mid-16th century, a new crop arrived in Italy that would change its destiny forever: tobacco. While the surrounding states, like the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (which succeeded the Republic of Florence) and the Papal States, quickly placed heavy taxes and state monopolies on the valuable plant, Cospaia remained a tax-free zone.

This made the tiny republic the perfect place to cultivate tobacco. Cospaia soon became one of the first centers of tobacco cultivation in Italy. The “Cospaiesi” grew high-quality tobacco and, because they paid no duties, could sell it at a fraction of the price of the official, state-sanctioned product. A thriving smuggling industry was born.

The entire economy of Cospaia became centered around this illicit trade. Its citizens became smugglers, moving their valuable product across the borders into Tuscany and the Papal States. This “lawless” reputation also made Cospaia a haven for others on the run. Political exiles, deserting soldiers, and petty criminals flocked to the tiny republic to escape the reach of ducal or papal law. It was a place where one could simply disappear, provided they didn’t cause too much trouble for the locals.

How Did It Last So Long?

One might wonder why two powerful states would tolerate a rogue, smuggling micro-nation on their shared border for nearly four centuries. The answer lies in a combination of inertia and mutual suspicion.

- Insignificant Size: Cospaia was simply too small to be considered a serious threat. For Florence and Rome, the effort required to conquer and administer a few hundred fiercely independent farmers wasn’t worth the trouble.

- A Convenient Buffer: Neither the Papal States nor Tuscany wanted the other to control the territory. Leaving it as a neutral, albeit anarchic, buffer zone was the easiest diplomatic solution. It was a state of mutually assured inconvenience.

- Economic Usefulness: While officially frowned upon, the smuggled tobacco from Cospaia was popular, and some corrupt officials on both sides likely benefited from the cross-border trade.

Thus, Cospaia enjoyed a de facto independence. It wasn’t officially recognized by any other state, but it was left alone, a strange anomaly surviving through the Renaissance, the Baroque period, and the Age of Enlightenment.

The End of a Peculiar Republic

The winds of change that would finally extinguish Cospaia’s perpetual freedom blew from France. The Napoleonic Wars at the turn of the 19th century completely upended the ancient political landscape of Italy. Old fiefdoms and city-states were swept away, and when the dust settled after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the new European order had no patience for quaint, centuries-old anomalies.

The existence of a lawless smuggling hub was no longer acceptable. On June 26, 1826, the fourteen remaining heads of Cospaia’s families signed an act of submission, dissolving their republic. The territory was divided between the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Papal States, finally closing the gap that had been created by a surveyor’s error 385 years earlier.

As a final nod to their unique history and economic importance, the Cospaiesi received a special compensation. Each citizen was awarded a silver papal coin, the “papetto”, as a farewell to their independence. More importantly, they were granted a license to continue cultivating tobacco—a crucial concession that allowed them to preserve their livelihood even after their republic was gone.

Today, the story of Cospaia is a beloved piece of local lore in the area around the modern town of San Giustino. While the republic is gone, its legacy lives on in the region’s strong tobacco-growing tradition. Cospaia stands as a remarkable testament to how history can be shaped not only by grand battles and powerful leaders but also by small mistakes, stubborn independence, and the irresistible allure of a tax-free life.