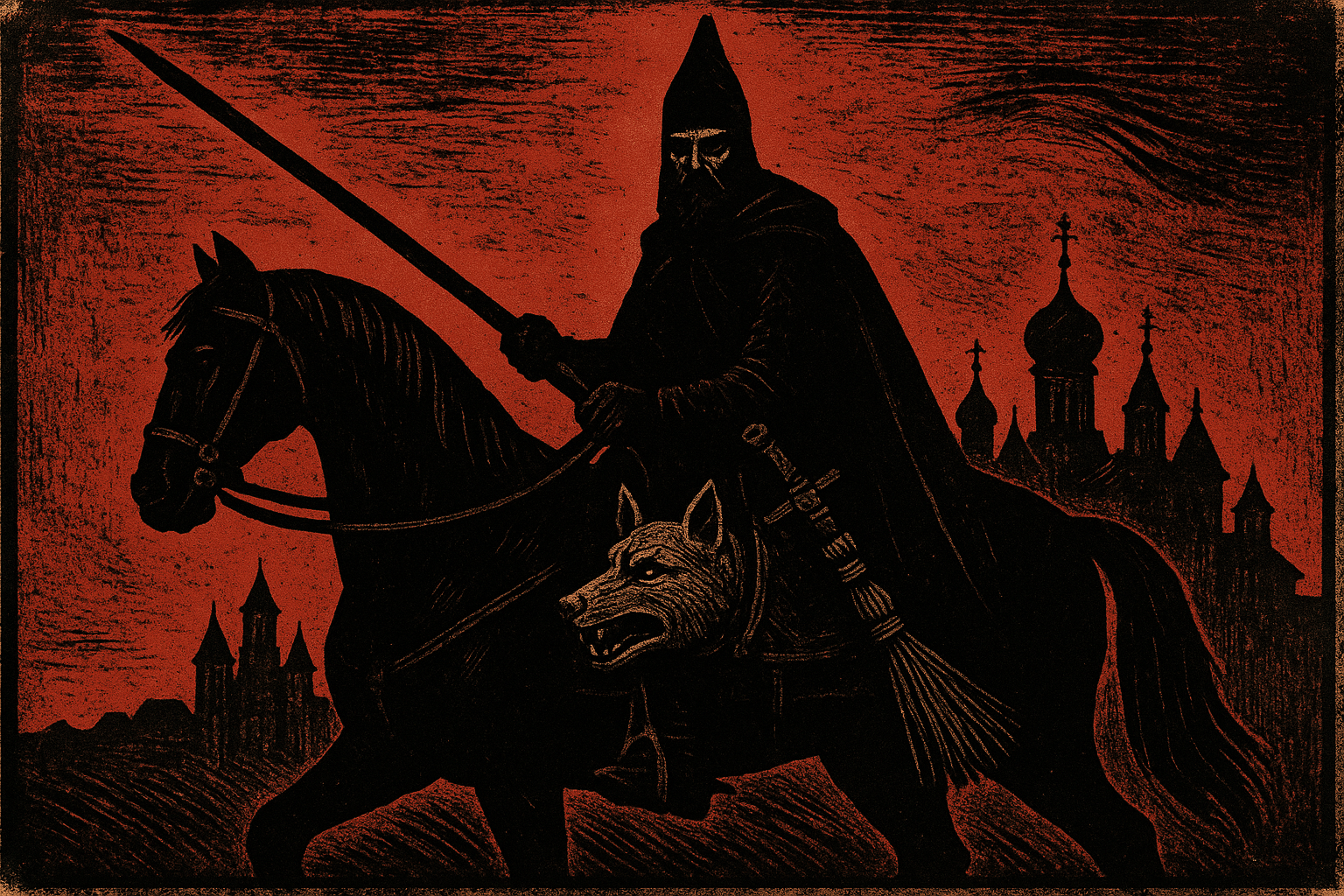

Imagine a black-clad rider thundering across the frozen Russian steppe. He sits astride a jet-black horse, and from his saddle hangs a gruesome trophy: the severed head of a dog. In his other hand, he clutches a broom. This is not a creature from a dark folktale, but a very real agent of the Tsar. This is an Oprichnik, and his arrival means terror, confiscation, and death. From 1565 to 1572, these men were the instruments of one of history’s most infamous and brutal state policies: the Oprichnina of Ivan IV, better known as Ivan the Terrible.

The Tsar’s Descent into Paranoia

To understand the Oprichnina, one must first understand the mind of the man who created it. Ivan IV’s early reign was promising. He was a reformer, a legislator, and a military conqueror who captured the great Tatar strongholds of Kazan and Astrakhan, significantly expanding Russian territory. Yet, a dark cloud of paranoia was gathering over the Tsar.

The pivotal moment came in 1560 with the death of his beloved first wife, Anastasia Romanovna. Ivan was convinced she had been poisoned by the boyars—the powerful, hereditary nobles of Russia. This suspicion, coupled with betrayals by some of his trusted advisors and military setbacks in the long-running Livonian War, plunged Ivan into a deep and vengeful paranoia. He saw traitors everywhere, especially within the ranks of the ancient aristocratic families who he believed sought to undermine his authority.

Birth of a State Within a State

In December 1564, Ivan stunned the country. In a masterful act of political theatre, he packed his treasures and his family, left Moscow, and secluded himself in the fortress of Aleksandrov Sloboda. From there, he issued two letters. The first, addressed to the high clergy, accused the boyars of treason and corruption. The second, read aloud to the common people of Moscow, assured them that they were not the object of his wrath. The effect was immediate. Panic gripped the capital. Fearing both a boyar takeover and a complete collapse of governance, a delegation of clergy and commoners journeyed through the snow to beg their Tsar to return.

Ivan agreed, but on his own terrifying terms. He demanded the power to punish traitors and evildoers with absolute authority—executing them and seizing their lands without interference from the Boyar Duma or the Church. To do this, he would divide the entire Russian state into two parts:

- The Zemschina: The majority of the country, which would continue to be administered by the traditional boyar institutions.

- The Oprichnina: A new territory, or “separate court”, taken under the Tsar’s direct and personal control. This domain comprised some of the wealthiest and most strategic lands in Russia, including districts within Moscow itself.

This was, in effect, a state-within-a-state, carved out of the heart of Russia and ruled solely by Ivan’s decree.

The Oprichniki: Hounds of the Tsar

To police his new domain and carry out his will, Ivan created a new force of about 1,000 (later growing to 6,000) loyal men: the Oprichniki. Dressed like dark monks in all black, they swore a personal oath of allegiance not to Russia, but to Ivan himself. They were his personal guard, his secret police, and his executioners, operating entirely outside the law.

Their symbols were deliberately terrifying:

- The Dog’s Head: This represented their mission to sniff out and bite the heels of traitors to the Tsar.

- The Broom: This symbolized their duty to sweep treason and corruption from the land.

Led by ruthless figures like the infamous Malyuta Skuratov, the Oprichniki were given free rein. They rode through the country, dispossessing established boyar families of their estates and giving the land to themselves. Resistance was met with swift and brutal violence. Torture, public execution, and murder became the order of the day.

A Reign of Terror Unleashed

The Oprichnina quickly spiraled from a tool of political intimidation into a full-blown reign of terror. While the boyars were the initial target, the violence soon spread to anyone who fell under the Tsar’s suspicion. One of the most prominent victims was Metropolitan Philip, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. When Philip publicly condemned the Oprichnina’s brutality during a service, Ivan had him deposed, imprisoned, and eventually murdered in his cell—strangled, according to tradition, by Malyuta Skuratov himself.

The terror reached its horrific apex in 1570 with the Massacre of Novgorod. Convinced that the ancient and proud city was plotting to defect to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Ivan led a massive Oprichnik army to confront the supposed treason. What followed was not an investigation, but a month-long orgy of destruction. For weeks, the Oprichniki tortured and slaughtered the city’s inhabitants. Thousands of men, women, and children were rounded up, tied together, and thrown into the freezing Volkhov River daily. Chroniclers estimate the death toll in the tens of thousands, a catastrophic blow from which the great city would never fully recover.

The End of an Era and its Lasting Scars

By 1571, the Oprichnina had become a force of pure chaos. It had shattered the Russian economy, depopulated vast tracts of land, and created an atmosphere of pervasive fear. Its military uselessness was laid bare that same year when a Crimean Tatar army bypassed the Oprichnik forces, sacked and burned Moscow to the ground, and carried off thousands of captives while Ivan’s “elite” guard proved utterly ineffective.

Seeing the catastrophic failure, Ivan the Terrible did what only an absolute autocrat could do. In 1572, he abruptly abolished the Oprichnina. The lands were reintegrated, the force was disbanded, and some of its key leaders were executed. Ivan even went so far as to forbid the very mention of the word “Oprichnina”, as if to erase his monstrous creation from memory.

But the scars remained. The Oprichnina achieved its primary political goal: it utterly broke the power of the old boyar aristocracy, eliminating any potential rivals to the Tsar. In doing so, it centralized power in the hands of the monarch to an unprecedented degree, laying the foundation for the absolute autocracy that would define Russia for centuries. It left behind a devastated economy, a traumatized populace, and a dark legacy of unquestioning submission to the violent power of the state—a shadow that would loom long over Russian history.