The Rhythm of Eight: Understanding the Nundinal Cycle

The term nundinae derives from the Latin phrase novem dies, meaning “nine days.” This immediately raises a question: why was it an eight-day week? The answer lies in the Romans’ penchant for inclusive counting. They counted both the start and end dates in a sequence. So, a new market day occurred every ninth day, but the cycle itself consisted of eight distinct days. Imagine a cycle labeled A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H. The next market day would fall on ‘A’ again, which was the ninth day from the previous ‘A’. This system was so ingrained that early Roman calendars, or fasti, had a column of letters from A to H, marking which day of the nundinal cycle it was, much like we have days of the week.

This eight-day rhythm was deeply ancient, predating even the founding of Rome itself and likely inherited from the Etruscans. According to the writer Macrobius, who wrote in the 5th century AD, the legendary Roman king Romulus was credited with first introducing this market cycle to encourage a balance between rural labor and urban commerce.

“It was a custom… for the country-folk to work in the fields for seven days and on the eighth day (since this was the market-day, or nundinae) to come to Rome to trade and also to take part in public business.” – Macrobius, Saturnalia

For most of the Roman Republic and the early Empire, this eight-day clock was the one that mattered most to ordinary people.

The Market Day: A City’s Weekly Rebirth

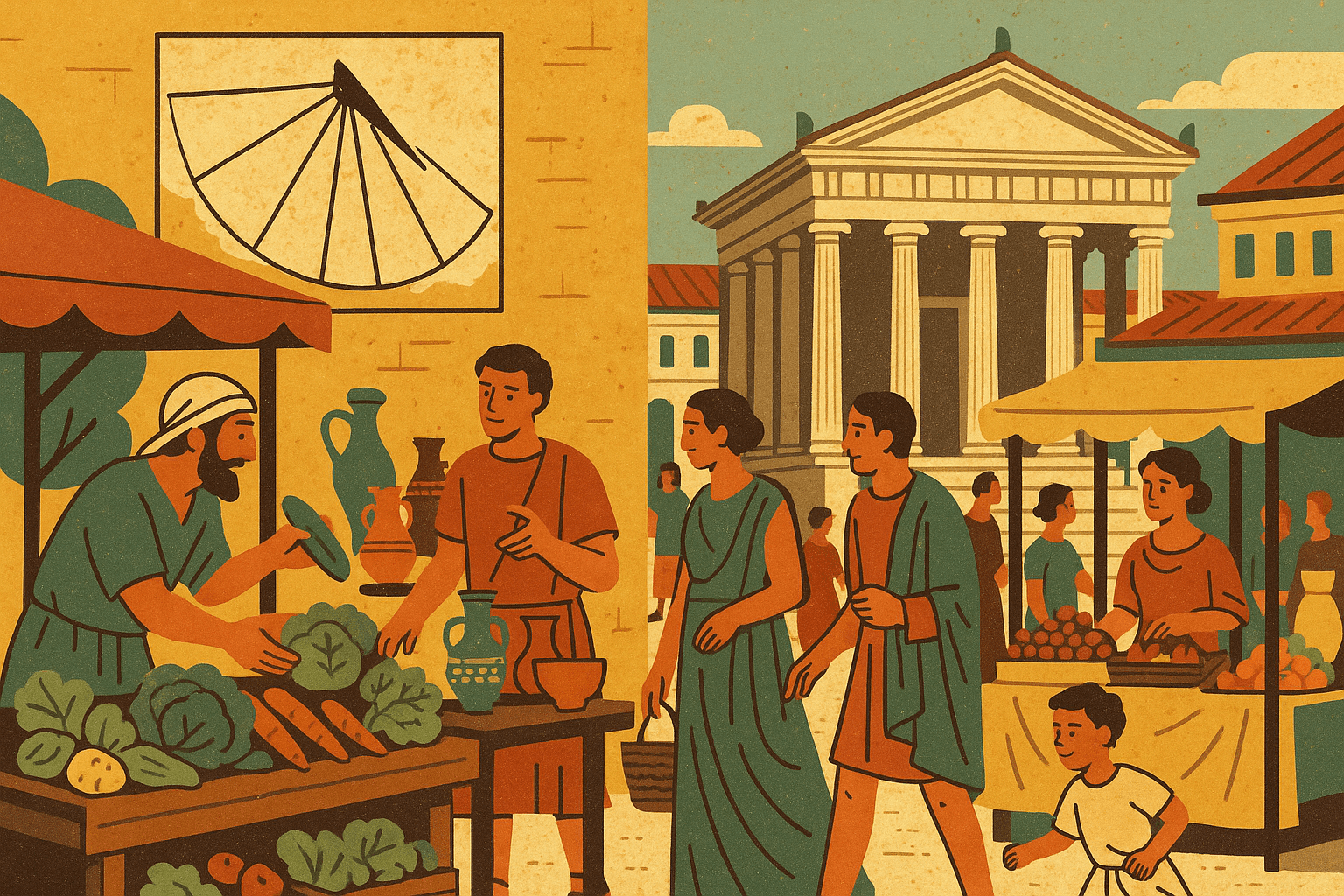

The eighth and final day of the cycle was the nundinae proper—the market day. On this day, the gates of the city would swing open to a flood of humanity. Farmers from the surrounding countryside, who spent the previous seven days tending their fields and livestock, would haul their goods into town. The air in the Roman Forum, and later in specialized forums and marketplaces, would become thick with the smells of fresh produce, baked bread, livestock, and the sweat of hard labor.

This was the primary engine of the Roman economy. Here, urban dwellers could buy everything they needed directly from the producers:

- Grains like spelt and wheat

- Olives, olive oil, and wine

- Cheeses, fruits, and vegetables

- Live poultry and other small animals

- Tools, pottery, textiles, and other crafted goods

The nundinae ensured a constant, predictable flow of essential goods from the agricultural hinterland to the consuming urban centers. It was a day for rural folk to sell their surplus, earn coin, and in turn purchase items they couldn’t produce themselves, like fine pottery or metal tools. This regular interaction was crucial for the economic integration of Roman territory, preventing cities from becoming isolated islands adrift in a sea of farmland.

More Than a Market: A Social and Political Hub

To see the nundinae as just a day for shopping is to miss its profound social importance. The crowds that gathered were a captive audience, making market day the perfect occasion for all manner of public and private business.

A Social Nexus: For the isolated farmer or rural villager, the nundinae was the main social event of the week. It was a time to see relatives, catch up on gossip, share news from distant parts of the region, and even arrange marriages. It was the day the community came together, reinforcing social bonds and a shared identity.

A Political Stage: Roman magistrates took full advantage of the assembled populace. Important edicts and public announcements were made on market days to ensure the widest possible dissemination. Furthermore, proposed laws had to be publicly posted for a period of a trinundinum—three nundinal cycles, or roughly 24 days—before a vote could be held. This ensured that even the rural citizenry, who were only in town on market days, had a chance to be informed about pending legislation that might affect them.

A Day for Justice: In the early Republic, court cases were often heard and settled on market days, as it was the one time all relevant parties and potential witnesses could be expected to be in one place. While rules later fluctuated, with some periods designating the nundinae as dies nefasti (days on which official legal or political business was forbidden), its informal role as a day to settle accounts and disputes remained.

The Sun Sets on the Eight-Day Week

So what happened to this ancient and enduring system? The answer lies in the East. As the Roman Empire expanded, it absorbed a vast array of cultures and ideas, including a different way of marking time: the seven-day week. This system, with its roots in Babylonian astronomy and Jewish tradition, assigned each day to a celestial body: the Sun, the Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn.

Soldiers stationed in Eastern provinces, merchants trading along the Silk Road, and followers of mystery cults like Mithraism began to bring the seven-day week back to the heart of the Empire. It gained traction throughout the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, existing alongside the traditional nundinae. For a time, a Roman might have known both that it was the day of Saturn (*dies Saturni*) and that it was, for example, day ‘C’ of the nundinal cycle.

The final shift came with the rise of Christianity. The Emperor Constantine the Great, in 321 AD, issued a famous edict that made Sunday (*dies Solis*, “the day of the venerable Sun”) an official day of rest for city dwellers and judges. While this was likely a move to accommodate both Christians who revered the Lord’s Day and followers of the popular Sol Invictus (“Unconquered Sun”) cult, it cemented the seven-day week into imperial law. The eight-day nundinae, while it may have persisted in some rural pockets for a time, lost its official significance. The steady, ancient rhythm that had governed Roman life for a millennium faded into history, replaced by the one we know today.

The story of the nundinae is a fascinating reminder that even the most fundamental structures of our lives, like the week itself, are not universal truths but cultural creations, shaped by the unique needs of a civilization.