A Culture Forged in Isolation

For centuries, the Chatham Islands, a remote archipelago some 800 kilometers east of mainland New Zealand, were a world unto themselves. The ancestors of the Moriori were Polynesian explorers who settled the islands around 1500 CE. adapting to the cold, windy, and resource-scarce environment. Unable to cultivate the tropical crops of their Polynesian homeland, they became masterful hunter-gatherers and fishers. Their society was small, with a population that likely never exceeded 2,000 people.

This isolation and the harsh realities of their environment forged a unique culture. Resources were precious, and survival depended on cooperation, not conflict. This pragmatism was codified into the central tenet of their society.

Nunuku’s Law: A Covenant of Peace

According to Moriori oral tradition, a revered ancestor named Nunuku-whenua witnessed the horror and waste of inter-tribal warfare. In a moment of profound wisdom, he established a sacred law that would define his people for generations. The law was simple and absolute: “Ka kore ano a muri, a te toto”, which translates to “No more fighting, no more killing.”

This wasn’t just a suggestion; it was a foundational moral and social code. Disputes would no longer be settled with lethal weapons. Instead, conflicts were resolved through ritual combat (tch-re huta), where participants fought with long staves. The fight would end as soon as the first blood was drawn, even a minor scratch. After the ritual, the matter was considered settled, and harmony was restored. For nearly 500 years, the Law of Nunuku governed the Moriori, creating a stable and genuinely peaceful civilization.

The Arrival of War

The Moriori’s isolation was shattered in 1791 with the arrival of the first European ship, the HMS Chatham. While initial contact was fraught with misunderstanding and some violence, it was the events of the 1830s that sealed their fate. European sealers and whalers began frequenting the islands, and in a catastrophic twist of fate, the brig Rodney brought news of the Chathams back to Māori iwi (tribes) in the Wellington and Taranaki regions of New Zealand.

At this time, mainland New Zealand was in the throes of the Musket Wars, a period of intense and brutal inter-tribal conflict fueled by newly acquired European firearms. Two displaced iwi, Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Tama, heard stories of the Chathams—a land of abundant resources and, crucially, a population that did not know how to fight. Desperate for a new home and seeing an opportunity, they organized an invasion.

In November 1835, the Rodney was hijacked and forced to carry 500 Māori warriors to the islands. A second ship followed in December with another 400. They arrived armed with muskets, clubs, and tomahawks, bringing a concept of total war (pakanga) that was utterly alien to their unsuspecting hosts.

The Fateful Decision

The Moriori were vastly outnumbered and completely unprepared for the ferocity of the newcomers. They gathered at a council at Te Awapātiki to decide how to respond. The younger generations argued for resistance, believing the Law of Nunuku should not apply to an external invader. However, the elders prevailed.

They argued that the Law was a sacred moral principle, a core part of their identity that could not be abandoned, no matter the circumstance. To break it would be to cease being Moriori. One elder, Tapata, is recorded as saying:

“…the law of Nunuku was not a strategy for victory; it was an emblem of who they were.”

Trusting in their traditions, the Moriori offered the newcomers peace, friendship, and a share of the islands’ resources. This peaceful overture was interpreted by the invaders not as a sign of moral strength, but as a confirmation of weakness.

The response was cataclysmic. On December 1, 1835, Ngāti Tama and Ngāti Mutunga began a systematic campaign of conquest. They swept across the islands, killing hundreds of Moriori men, women, and children. It was a massacre. Those who were not killed immediately were enslaved (becoming taurekareka), subjected to brutal treatment, forced labor, and cannibalism. They were forbidden from marrying or having children with each other, a deliberate policy to extinguish their lineage. The Law of Nunuku had been met with a level of violence its creators could never have imagined.

A Legacy Reclaimed

The devastation was almost total. Of the estimated 2,000 Moriori in 1835, only 101 remained by 1862. Their culture was shattered, their freedom lost, and their lands confiscated. For over a century, a false narrative, often called the “extinction myth”, was perpetuated. This story claimed the Moriori were an inferior, lazy race who had died out naturally. This revisionist history served to justify their dispossession and erase the truth of the genocide.

However, the Moriori did not die out. Their descendants have fought tirelessly to correct the historical record and revitalize their culture. Through research, advocacy, and submissions to the Waitangi Tribunal (a New Zealand commission that investigates treaty breaches), they have successfully reclaimed their identity and story.

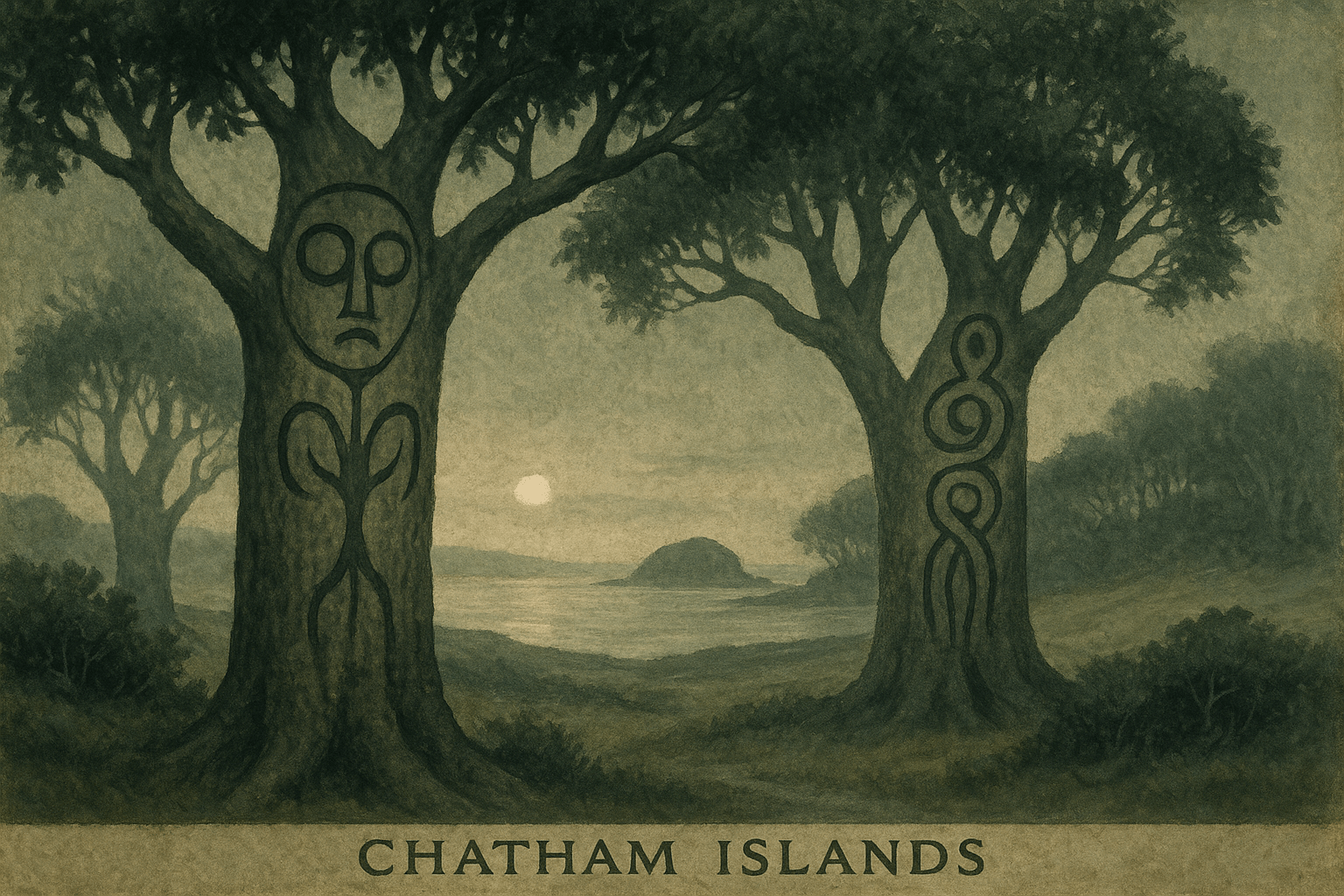

Today, Moriori culture is experiencing a powerful renaissance. Their language is being revived, their ancient tree carvings (rākau momori) are being preserved, and their traditions are being taught to new generations. The story of the Moriori is no longer just one of victimhood; it is a story of resilience, cultural survival, and the enduring power of identity.

The tragedy of the Moriori remains a profound and disturbing lesson. It highlights the vulnerability of a peaceful society in a world that does not uniformly value peace. But it is also a powerful testament to a people who, faced with annihilation, chose to uphold their most sacred principle. Their commitment to peace was not a weakness, but a conscious, deeply held belief that defined them—and continues to define their descendants today.