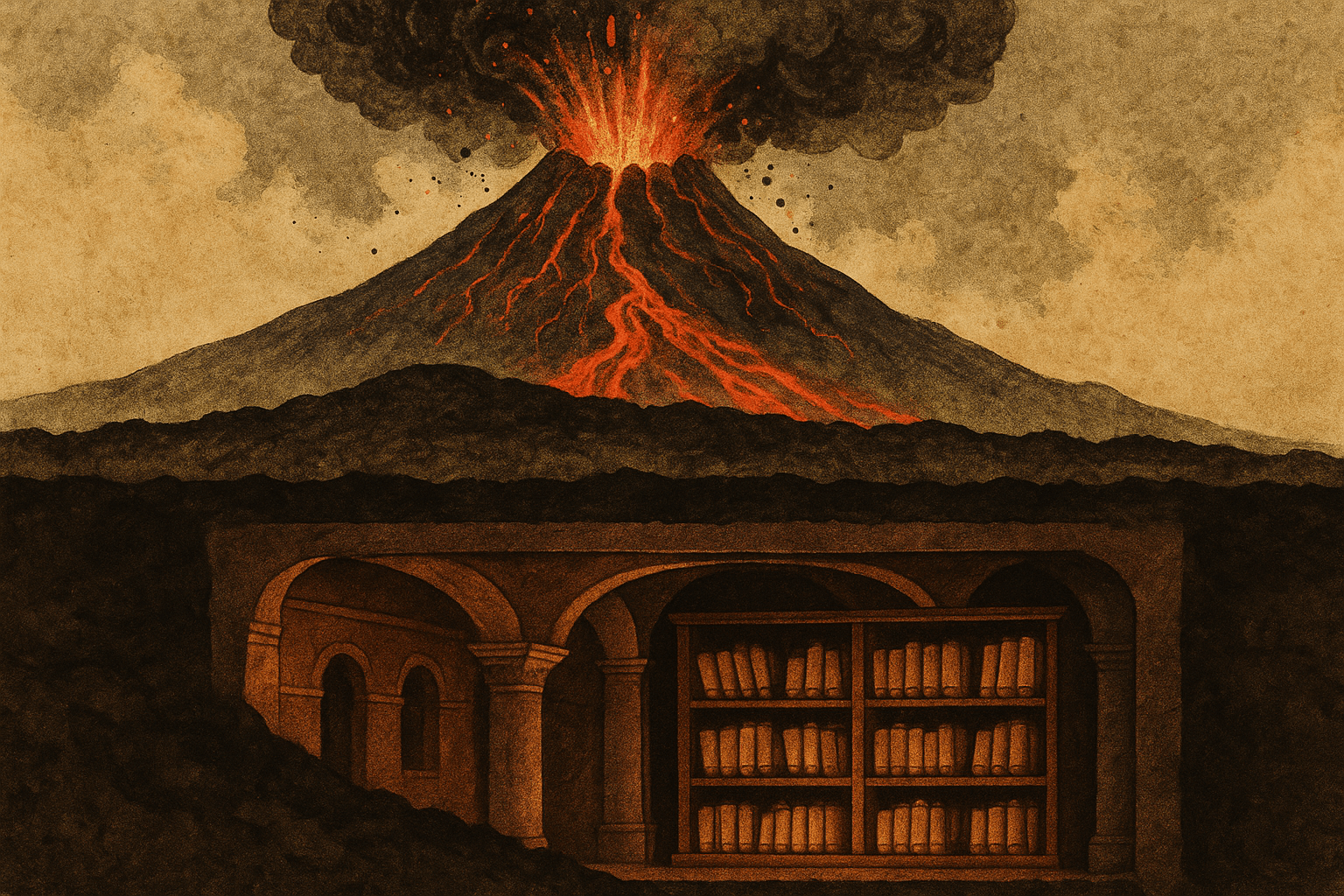

When we think of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, our minds immediately conjure images of Pompeii—of bodies frozen in ash, of a city preserved in a moment of terror. But just a few miles away, the neighboring coastal town of Herculaneum suffered a different, and in some ways, more extraordinary fate. While Pompeii was slowly buried under a rain of pumice and ash, Herculaneum was slammed by a series of superheated pyroclastic surges. The intense heat, reaching over 500°C (930°F), instantly carbonized organic materials, turning wood, food, and even people into charcoal before entombing the city under 20 meters of solidified volcanic rock. This cataclysm, a destroyer of life, was also an unparalleled preserver of history. And nestled within a magnificent seaside villa, it preserved the greatest of all historical treasures: the only intact library to survive from the classical world.

A Palace of Learning Buried in Fire

The story of the library begins with the villa that housed it. Discovered in the 1750s during early, haphazard tunneling explorations, the sheer scale and luxury of the “Villa of the Papyri” stunned its finders. This sprawling estate, stretching down to the ancient coastline, was one of the most opulent homes in the Roman world. Its gardens were adorned with a spectacular collection of bronze and marble sculptures, many of which are now masterpieces of museum collections.

Historians believe the villa belonged to Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, a wealthy Roman aristocrat and, most notably, the father-in-law of Julius Caesar. Piso was a known patron of philosophy, particularly of the Epicurean school. This connection became startlingly clear when excavators, sifting through the layers of hardened mud and rock, found what they first believed to be simple logs or lumps of charcoal. Many were discarded or broken apart before one was accidentally dropped, revealing faint markings on the inside. They weren’t logs; they were papyrus scrolls, flash-cooked by the volcano’s heat into brittle, carbonized cylinders.

Suddenly, the excavators realized they had stumbled upon something unprecedented. They had found a Roman library. An entire room, a small study off the main peristyle, was packed with shelves holding over 1,800 scrolls. It was a time capsule of ancient knowledge.

The 250-Year Challenge: Reading the Unreadable

The euphoria of the discovery quickly gave way to a formidable challenge. How could anyone possibly read these scrolls? They were as black as coal and so fragile that the slightest touch could cause them to crumble into dust. The ink used by the Romans was also carbon-based, made from soot and gum. This created the ultimate archaeological puzzle: black ink on a black, carbonized background. Visually, they were almost identical.

Early attempts at unrolling were heroic, if often destructive. In the 18th century, an ingenious friar named Antonio Piaggio invented a machine that could gently pull the layers of the papyrus apart, millimeter by millimeter, over a period of years. While he had some success, the process frequently destroyed as much text as it revealed. Later experiments involving chemicals or attempts to slice the scrolls open proved even more disastrous.

For over two centuries, the majority of the scrolls remained silent, their contents a mystery. The fragments that had been painstakingly unrolled revealed a specific collection: a library almost entirely dedicated to the works of a single Greek philosopher, Philodemus of Gadara. He was an Epicurean philosopher-in-residence at the villa, and the scrolls contained his treatises on ethics, music, rhetoric, and death. While this was a monumental recovery of a Hellenistic thinker’s work, it left scholars wondering: where were the famous authors? Where were Plato, Aristotle, Homer, or the lost plays of Sophocles?

Virtual Unwrapping: AI and the Synchrotron

The breakthrough came not from a new mechanical device, but from a radical leap in technology. In the 21st century, scientists began to apply advanced imaging techniques to the problem. They turned to particle accelerators, known as synchrotrons, which can produce X-rays billions of times brighter than those in a hospital.

Using a technique called X-ray phase-contrast tomography, researchers could scan a still-rolled scroll and create a detailed 3D digital model. Critically, these powerful X-rays could detect not the color of the ink, but its subtle physical difference from the papyrus. The ink sat on the surface of the papyrus fibers, creating a minute change in texture and height, sometimes just a few microns thick. The X-rays could pick up this tiny topographical difference, revealing the ghost of the writing hidden within the carbonized mass.

However, detecting the ink was only half the battle. The resulting data was a chaotic mess of overlapping layers. This is where artificial intelligence and machine learning entered the picture. Initiatives like the “Vesuvius Challenge” have crowdsourced the problem, offering prizes to computer scientists and enthusiasts who can develop algorithms to “virtually unwrap” the scrolls. These AI models are trained to recognize the subtle patterns of the ink, segment the coiled layers of papyrus, and flatten them into a readable image. In 2023, this approach yielded its first major success: the word “πορφύρας” (porphyras), meaning “purple”, was clearly read from a previously unopened scroll, proving the method’s incredible potential.

What Secrets Still Lie Within?

The successful application of AI has opened the floodgates. Teams are now working to decipher entire passages and scrolls, promising a new golden age of discovery for the classics. While many more works of Philodemus are expected, the true dream is what else might be hidden.

The current collection appears to be a highly specialized personal library of a Greek philosopher. Many archaeologists speculate that the villa’s main library, which would have contained the more famous Latin works of history, poetry, and oratory, has yet to be found. The villa has only been partially excavated through tunnels; the vast majority of it remains buried. Might there be another room, a grander library, waiting for future archaeologists? In it could be:

- The lost books of Livy’s History of Rome

- Aristotle’s lost second book of Poetics on comedy

- The complete poems of Sappho, of which only fragments survive

- Lost plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides

- Original Roman works we don’t even know existed

The Library of the Villa of the Papyri is more than just a collection of ancient texts. It is a direct bridge to the intellectual world of ancient Rome. For centuries, it has been a tantalizing promise, a locked room in the house of history. Now, thanks to the fusion of archaeology and artificial intelligence, we are finally finding the key. The words that were silenced by Vesuvius are beginning to speak again, and we are only just beginning to listen.