Imagine the Age of Sail. A merchant vessel, heavy with cargo from the colonies, plods across the Atlantic. On the horizon, a swift, heavily-armed ship appears, flying no national flag. Its crew is a hardened pack of sea wolves. Is it a pirate, bent on plunder and murder? Or is it a naval warship, enforcing a blockade? For a terrifying period, the answer could be a third, more ambiguous option: the privateer.

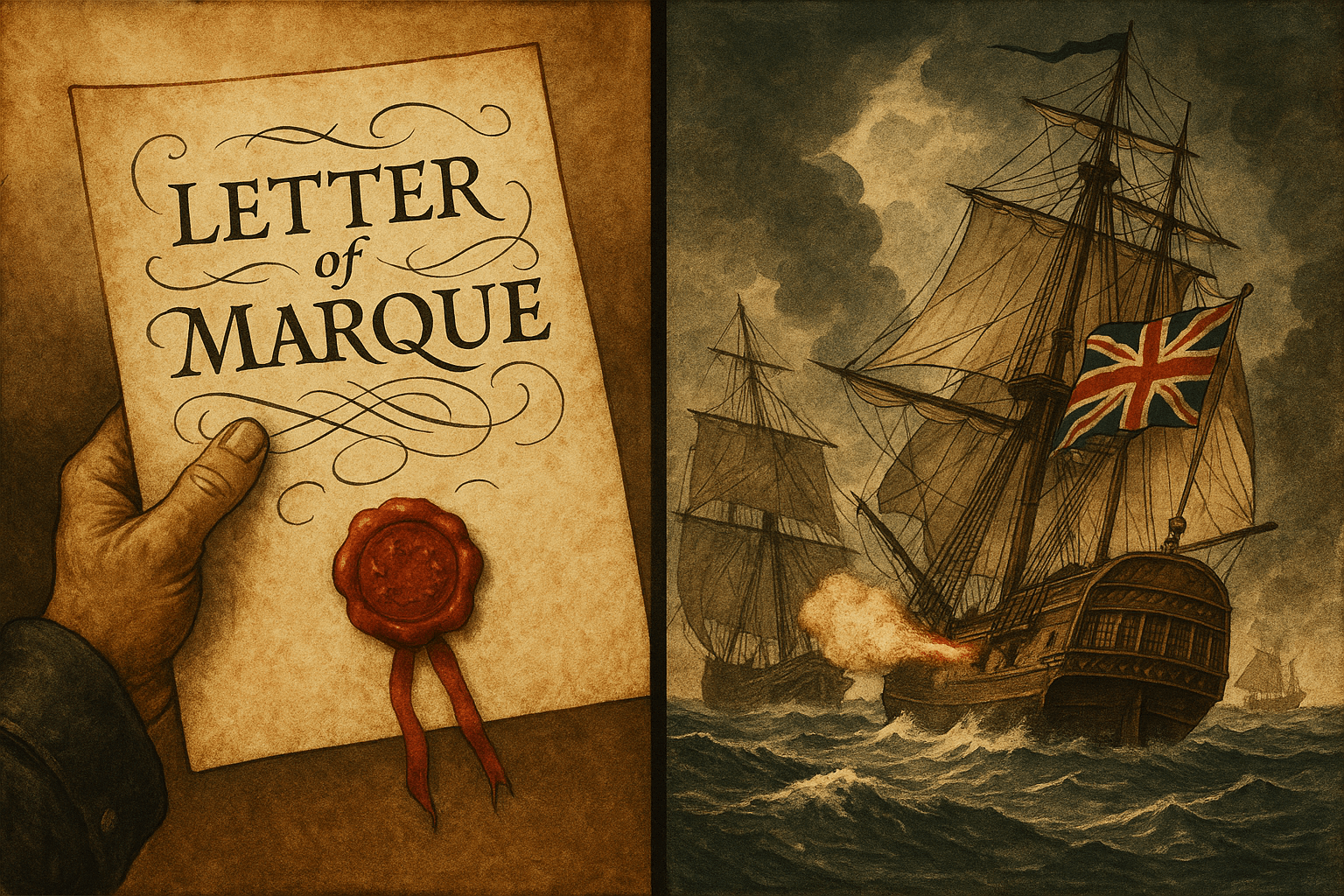

These were not common pirates, nor were they enlisted sailors of a national navy. They were private citizens, captains of their own ships, who operated under a special license from their government: the Letter of Marque. This single document was the thin, often-smudged line separating a celebrated patriot from a hanged pirate, turning the high seas into a theater of legalized, profit-driven warfare.

What Exactly Was a Letter of Marque?

In its simplest form, a Letter of Marque and Reprisal was a government commission authorizing a private individual to attack and capture vessels belonging to an enemy nation. The concept originated in the medieval period as a form of judicial “reprisal.” If a merchant from one kingdom had their goods stolen by a subject of another, and their government refused to provide justice, the merchant’s own sovereign could issue a letter authorizing them to “make a reprisal” and seize goods of equal value from any ship of the offending nation.

By the 16th and 17th centuries, this evolved from specific retaliation into a general tool of naval warfare. During a declared war, a government would issue broad Letters of Marque to any ship owner willing to arm their vessel and hunt the enemy. The captured ships and their cargo, known as prizes, were then the privateer’s to keep—after a chunk was given to the government and the courts, of course.

The Rules of the Game: Privateering vs. Piracy

So, what truly separated a heroic privateer like Sir Francis Drake (to the English) from a villainous pirate like Blackbeard? The difference, while crucial, often depended on whose flag you were sailing under. Legally, however, the distinctions were clear.

- Authorization: A privateer operated with the explicit, written permission of a sovereign government. A pirate had no authority but their own greed and the cannon at their side.

- Legitimate Targets: Privateers were only legally permitted to attack shipping from nations with which their country was at war. Attacking a neutral ship or a vessel from their own country was an act of piracy. Pirates, by contrast, saw every ship as a potential target.

- Adjudication: This was the key. When a privateer captured a prize, they couldn’t just sail off with the loot. The captured ship had to be brought to a friendly port and put before an Admiralty or “Prize Court.” The court would examine the ship’s papers and the privateer’s Letter of Marque to determine if the capture was legal. Only after the prize was “condemned” by the court could the ship and its cargo be sold and the profits distributed.

- Treatment of Prisoners: A captured privateer was, in theory, to be treated as a prisoner of war by the enemy. A captured pirate could expect a short trial and a long drop from the gallows.

Of course, on the violent, lawless expanse of the ocean, these rules were often bent or broken. A privateer whose Letter of Marque expired with a peace treaty might be tempted to continue their profitable enterprise, instantly becoming a pirate in the eyes of the world.

A Win-Win for Cash-Strapped Kingdoms

Why would a government essentially outsource its naval warfare to profit-seeking entrepreneurs? The answer is simple economics and strategy. Building, crewing, and maintaining a large, state-funded navy was astronomically expensive. Privateering offered a brilliant solution.

It acted as a massive force multiplier. With the stroke of a pen, a nation could unleash hundreds of armed vessels against its enemy’s merchant fleet, strangling their trade and crippling their economy at virtually no cost to the state treasury. The private investors and ship owners shouldered all the financial risk of arming the ship and paying the crew. The government simply sanctioned the activity and took a percentage of the profits.

The lure of prize money was a powerful incentive. It attracted the most skilled and daring sailors, who might otherwise have avoided the navy, and encouraged merchants to convert their ships for war. For a nation like the fledgling United States during the American Revolution, with its tiny Continental Navy, privateers were indispensable. They captured hundreds of British ships, providing much-needed supplies and wreaking havoc on British commerce.

Famous Faces of Licensed Piracy

History is filled with famous privateers whose legacies are a mix of heroism and opportunism.

Sir Francis Drake was Queen Elizabeth I’s favored “sea dog.” While England and Spain were not officially at war for much of his career, Elizabeth secretly encouraged and funded his raids against Spain’s treasure fleets in the New World. To the English, he was a knighted hero who brought back immense wealth. To the Spanish, he was nothing more than a detestable pirate, El Draque.

Another fascinating figure is Jean Laffite. Operating out of the swamps of Louisiana in the early 19th century, he ran a massive smuggling and privateering empire. The United States government declared him an outlaw. Yet, during the War of 1812, Laffite and his men provided crucial support—including cannon and experienced gunners—to Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans, helping to secure a stunning American victory against the British. In return, he and his men received a full pardon, transforming from pirates to patriots overnight.

The End of an Era

As the 19th century progressed, the world began to change. Nations built larger, more professional, and more disciplined navies. The actions of unpredictable privateers, who might accidentally attack a neutral ship and spark a diplomatic crisis, became more of a liability than an asset.

The final death knell for privateering came in 1856. Following the Crimean War, the major European powers signed the Declaration of Paris. One of its main articles was the formal abolition of privateering. While the United States, wanting to keep its options open, never formally ratified the declaration, the age of the licensed privateer was effectively over. The world had moved on to state-controlled navies and clearer lines of international conflict.

The Letter of Marque remains a fascinating relic of a time when the boundaries of war, commerce, and piracy were dangerously blurred. It was a pragmatic tool of statecraft that unleashed the ambition and greed of private individuals for national gain, creating legends and nightmares on the high seas in equal measure.