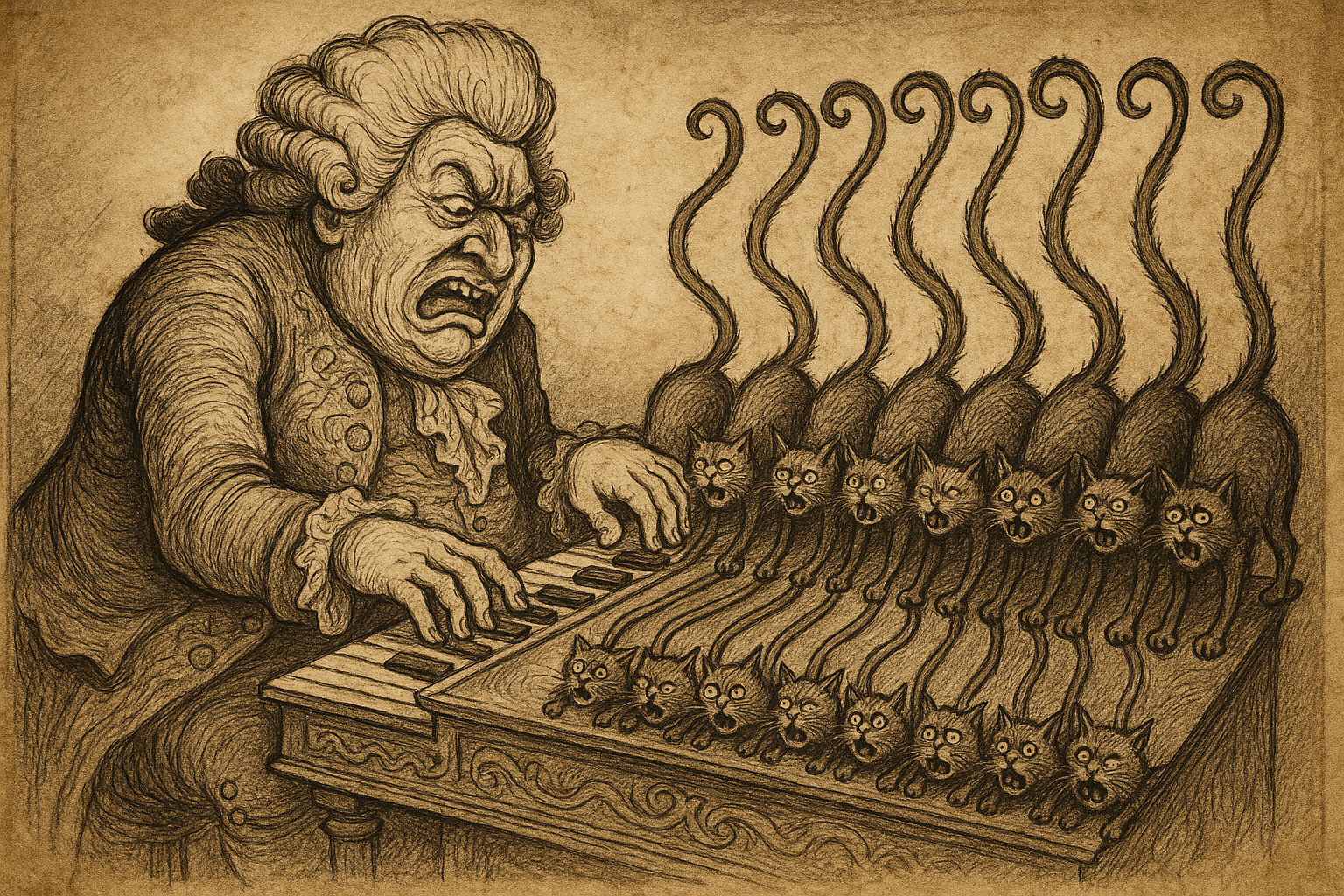

History is filled with strange inventions, gruesome tales, and ideas so bizarre they blur the line between fact and fiction. Few legends, however, are as uniquely macabre and unsettling as that of the Katzenklavier, or “Cat Organ.” The concept is as simple as it is horrifying: a musical instrument composed of a row of live cats, their tails trapped beneath a keyboard, who are made to shriek in specific pitches when a player strikes the keys. But did this monstrous creation ever truly exist? Or was it a dark figment of the imagination, a satirical critique born from an era of casual cruelty?

The First Detailed Account: Athanasius Kircher’s Bizarre Cure

The most famous and detailed description of a cat organ comes from the brilliant but eccentric 17th-century German Jesuit scholar, Athanasius Kircher. In his 1650 magnum opus on music and acoustics, Musurgia Universalis, Kircher describes the instrument with unnerving precision. He paints a picture of a large box containing a line of live cats, carefully selected and arranged “according to the pitch of their natural voices.” The cats are confined in small cages with only their tails sticking out, positioned beneath a keyboard. Each key is connected to a sharp spike or nail.

When a musician presses a key, the mechanism drives the spike into the corresponding cat’s tail. The animal’s subsequent cry of pain serves as the musical “note.” According to Kircher, the purpose of this diabolical contraption was not to create beautiful symphonies. Instead, he presents it as a form of shock therapy, allegedly constructed to treat a melancholic prince who had fallen into a deep, catatonic stupor.

As the story goes, the prince was placed before the Katzenklavier. When the organist began to play, the resulting cacophony of feline shrieks was so shocking and absurdly horrifying that the prince burst into laughter, breaking his catatonic state and returning to his senses. For Kircher, the instrument was a success—not as a musical device, but as a psychological tool designed to jolt a mind from its despair through an overwhelming spectacle of the bizarre.

Tracing the Legend’s Roots

While Kircher provided the most enduring image of the cat organ (complete with a gruesome illustration), he may not have invented the idea. The concept appears in earlier, though more ambiguous, forms. The 19th-century French musicologist Jean-Baptiste Weckerlin, in his book Musiciana, extraits d’ouvrages rares ou bizarres, claimed that such an instrument was used during a festival in Brussels in 1549 to entertain the future Philip II of Spain.

Weckerlin describes a parade float featuring a bear playing a “pipe organ” made of about twenty cats. Levers pulled on the cats’ tails to produce the “music.” However, Weckerlin was writing more than 300 years after the alleged event, and his sources are often shaky. This account feels less like a functional instrument and more like a carnivalesque spectacle, designed for a one-off shock rather than repeatable musical performance.

The theme of animal cruelty as spectacle was, unfortunately, common in early modern Europe. Events like public cat-burnings (kattesinnes) and bear-baiting were considered legitimate forms of entertainment. In this context, a cat organ, while extreme, fits within a known cultural pattern of using animal suffering for human amusement.

A Thought Experiment in Cruelty and Satire

So, was it real? All evidence points to “no.” No physical remains of a cat organ have ever been discovered. No reliable, firsthand eyewitness accounts exist. The stories are always presented as historical oddities or second-hand reports. Beyond the lack of physical proof, the practical challenges of building a functional Katzenklavier are immense:

- Tuning:** How could one possibly find enough cats whose natural meows corresponded to a musical scale? A cat’s voice is not a fixed, stable pitch.

- Performance:** A cry of pain is a shriek, not a clean, sustained musical note. The resulting sound would be a chaotic, atonal mess, not the “lamentable music” Kircher described.

- Endurance:** The cats would quickly become hoarse, frenzied, or unconscious from terror and pain, rendering the “instrument” useless after only a few moments.

Given these impossibilities, it is far more likely that the cat organ existed as a thought experiment or a piece of biting satire. By imagining the most absurdly cruel instrument possible, writers like Kircher were potentially engaging in several layers of commentary.

First, it serves as a critique of cruelty itself. By taking the era’s casual disregard for animal life to its most grotesque and illogical conclusion, the cat organ highlights the senselessness of such attitudes. It’s a reductio ad absurdum of the idea that animals exist solely for human use and entertainment.

Second, it can be read as a satire on the pursuit of novelty. The Renaissance and Baroque periods were ages of invention, filled with scholars and mechanics creating “wondrous machines” and cabinets of curiosities. The cat organ mocks this impulse, parodying the drive to create ever more elaborate and “ingenious” devices, regardless of their moral or practical implications. It asks: just because we can imagine something, does that make it a worthy pursuit?

Why the Macabre Legend Endures

The Katzenklavier was almost certainly a phantom of the historical imagination—a dark joke, a satirical sketch, a legend passed down as a bizarre “what if.” Yet, the story continues to fascinate and horrify us centuries later. Its power lies not in its reality, but in what it represents.

The legend of the cat organ is a stark reflection of a past where the boundaries of empathy were drawn much differently. It serves as a powerful, if grotesque, landmark in the history of animal welfare, reminding us how far attitudes have shifted. It taps into a primal fear of suffering and the perversion of art, making us question the very nature of music, creativity, and human ingenuity.

Ultimately, the cat organ is a ghost story from the history of science and music. It’s a chilling reminder that the darkest creations are often not made of wood and wire, but are constructed entirely within the human mind.