When you think of ancient law, one name almost inevitably springs to mind: Hammurabi. His famous code, with its “eye for an eye” philosophy, is etched into the bedrock of world history as a monumental step towards organized justice. But here’s a secret history buffs know well: Hammurabi was not the first. He was the culmination of a legal tradition that had been brewing in the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia for centuries. He stood on the shoulders of legal giants, kings and reformers who had already begun the hard work of turning abstract ideas of fairness into written, public law.

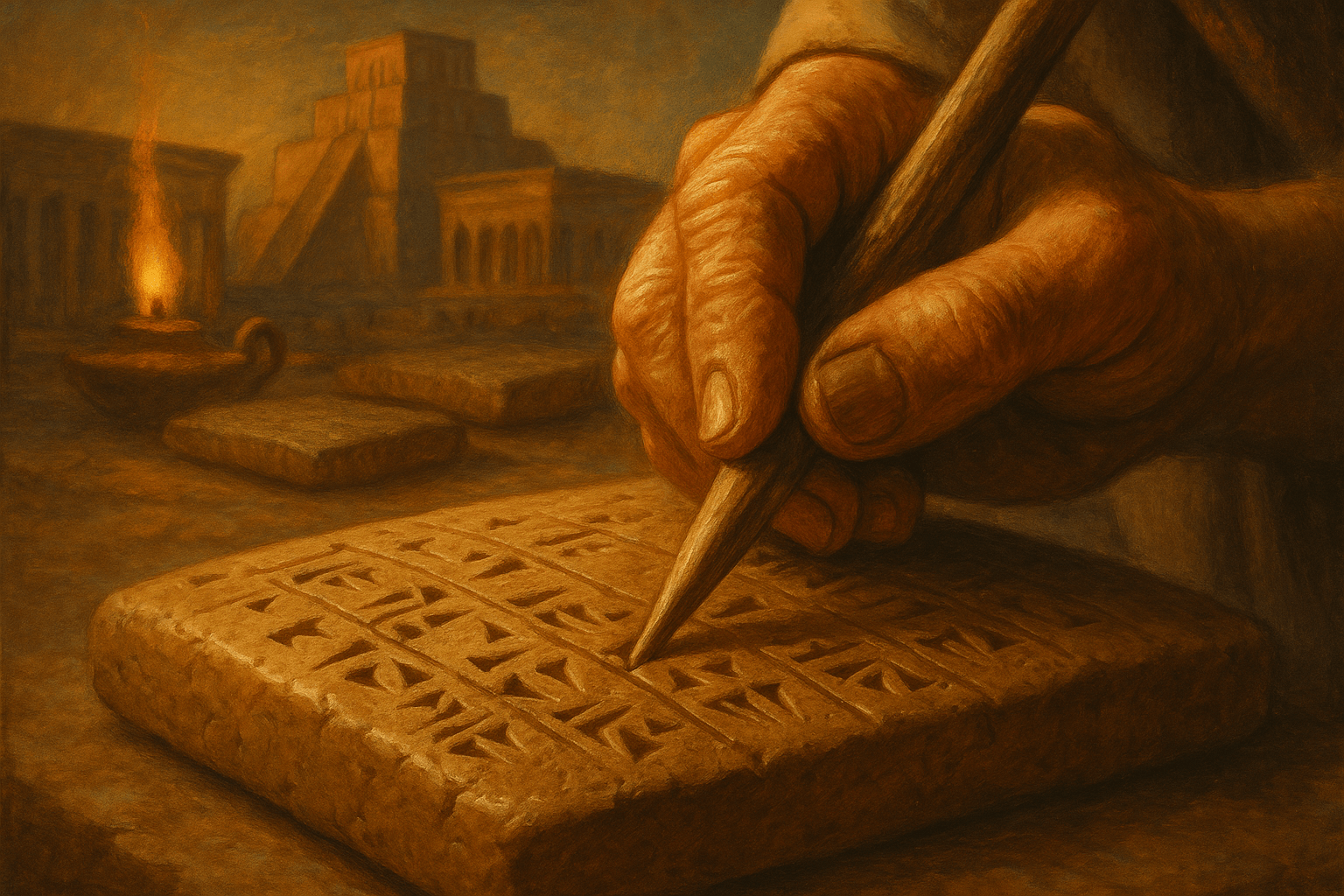

To truly understand the evolution of justice, we must travel back past Babylon circa 1754 BCE and explore the world of Hammurabi’s predecessors. This is a journey into the very dawn of codified law, where the concepts of social order, punishment, and royal responsibility were first chiseled into clay.

A Cry for Justice: The Reforms of Urukagina

Our first stop is the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, around 2400 BCE. Here we meet a ruler named Urukagina. He wasn’t writing a comprehensive law code in the way we think of it today; instead, he was a reformer, a man who saw a system riddled with corruption and sought to fix it. Inscriptions from his reign paint a grim picture of his city before he took power. Priests and wealthy officials were exploiting the common people, levying exorbitant taxes and seizing property at will.

As the inscriptions tell it, “the boatmen, their boats were seized. The shepherds, their sheep and donkeys were seized… The temple overseers were taking the fruit from the gardens of the poor.” It was a society where the powerful preyed on the vulnerable.

Urukagina’s reforms were a direct response. He declared that he had made a “covenant with the god Ningirsu” to end this injustice. His decrees aimed to:

- Protect widows and orphans from exploitation.

- Curb the power of foremen and priests, preventing them from seizing the property of “the sons of a poor man.”

- Cancel debts for those forced into servitude.

- Establish that when a “man of high rank” wanted to buy the house of a commoner, he had to pay a fair price in silver, and the commoner had the right to refuse the sale.

While not a formal law code, the Reforms of Urukagina represent a monumental first step. It was a public declaration that justice was the king’s responsibility and that the state had an obligation to protect its weakest members from the powerful. It established a principle that would echo through all subsequent Mesopotamian law.

The Oldest Surviving Law Code: The Code of Ur-Nammu

Roughly 300 years after Urukagina, around 2100 BCE, we arrive at the great city of Ur. Its founder, King Ur-Nammu, presided over a period of peace and prosperity known as the “Sumerian Renaissance.” To maintain this stability, he promulgated what is now recognized as the oldest surviving law code in history.

Written in Sumerian on clay tablets, the Code of Ur-Nammu is far more structured than Urukagina’s reforms. It begins with a prologue that establishes the king’s divine right to rule and his mission: to “establish justice in the land, to banish malediction, violence, and strife.”

What’s most striking about this code is its approach to punishment. Unlike the brutal retaliatory justice of Hammurabi, Ur-Nammu’s code primarily relied on monetary compensation. Consider these examples:

- “If a man knocks out the eye of another man, he shall weigh out one-half mina of silver.”

- “If a man knocks out a tooth of another man, he shall pay two shekels of silver.”

- “If a man, in the course of a scuffle, smashes the limb of another man with a club, he shall pay one mina of silver.”

This is a world away from “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” The focus was on restitution, not retribution. The code also dealt with matters of divorce, witchcraft, and runaway slaves, always with a clear set of penalties—usually fines. The only capital offenses mentioned are for murder, robbery, deflowering another man’s virgin wife, and adultery, indicating that while justice was tempered, it was not soft on the most severe crimes.

A More Complex Society: The Code of Lipit-Ishtar

Continuing our journey forward in time, we land in the city of Isin around 1930 BCE. The Sumerian power of Ur has faded, and a new Amorite king, Lipit-Ishtar, is on the throne. His code, written in Sumerian, serves as a crucial bridge between the compensatory laws of Ur-Nammu and the later severity of Hammurabi a century and a half later.

The Code of Lipit-Ishtar is more detailed and extensive than Ur-Nammu’s, reflecting an increasingly complex society. Fragments of the code, many of which survived as copies used by student scribes for practice, give us insight into a wide range of legal issues:

- Property and Contracts: It contains detailed laws about boat rentals, the hiring of oxen, and responsibilities for rented property. For example, if a man rented an ox and damaged its eye, he had to pay half its price in silver.

- Family Law: The code addresses inheritance rights, the status of children from second wives and slave women, and false accusations of marital infidelity.

- Land Use: There are specific laws concerning the upkeep of orchards. If a man trespassed on another’s orchard and was caught there for stealing, he had to pay ten shekels of silver.

Like his predecessors, Lipit-Ishtar’s prologue states that he was called by the gods “to establish justice in the land… and to bring well-being to the Sumerians and Akkadians.” He also proudly states in his epilogue that through his justice, “the orphan did not fall prey to the rich, the widow did not fall prey to the powerful.” The thread of social justice that began with Urukagina remains strong.

The Legacy of Hammurabi’s Predecessors

When Hammurabi of Babylon finally carved his famous 282 laws onto a towering black diorite stele, he was not inventing the concept of royal justice; he was perfecting and, in some ways, hardening it. He inherited a tradition that was already centuries old.

The evolution is clear:

- Urukagina (c. 2400 BCE): Established the principle of the king as a protector against injustice and corruption.

- Ur-Nammu (c. 2100 BCE): Created the first true law code, emphasizing financial compensation over physical retaliation.

- Lipit-Ishtar (c. 1930 BCE): Expanded the scope of the law to cover a more complex urban society, while maintaining a mix of fines and other penalties.

Hammurabi’s code was more systematic, more comprehensive, and famously, more brutal. His shift toward lex talionis (“the law of retaliation”) marks a significant change in legal philosophy from the fines of Ur-Nammu. Perhaps this reflected the more militaristic and consolidated nature of his Babylonian empire, or perhaps it was seen as a stronger deterrent.

By studying these earlier codes, we see that Hammurabi’s Code was not a sudden flash of legal genius. It was the product of a long, evolving conversation about fairness, order, and the role of a ruler—a conversation started on clay tablets in Sumerian cities long before Babylon became the master of Mesopotamia. These ancient lawgivers were the true pioneers, taking the first audacious steps to build a society governed not by whim, but by written law.