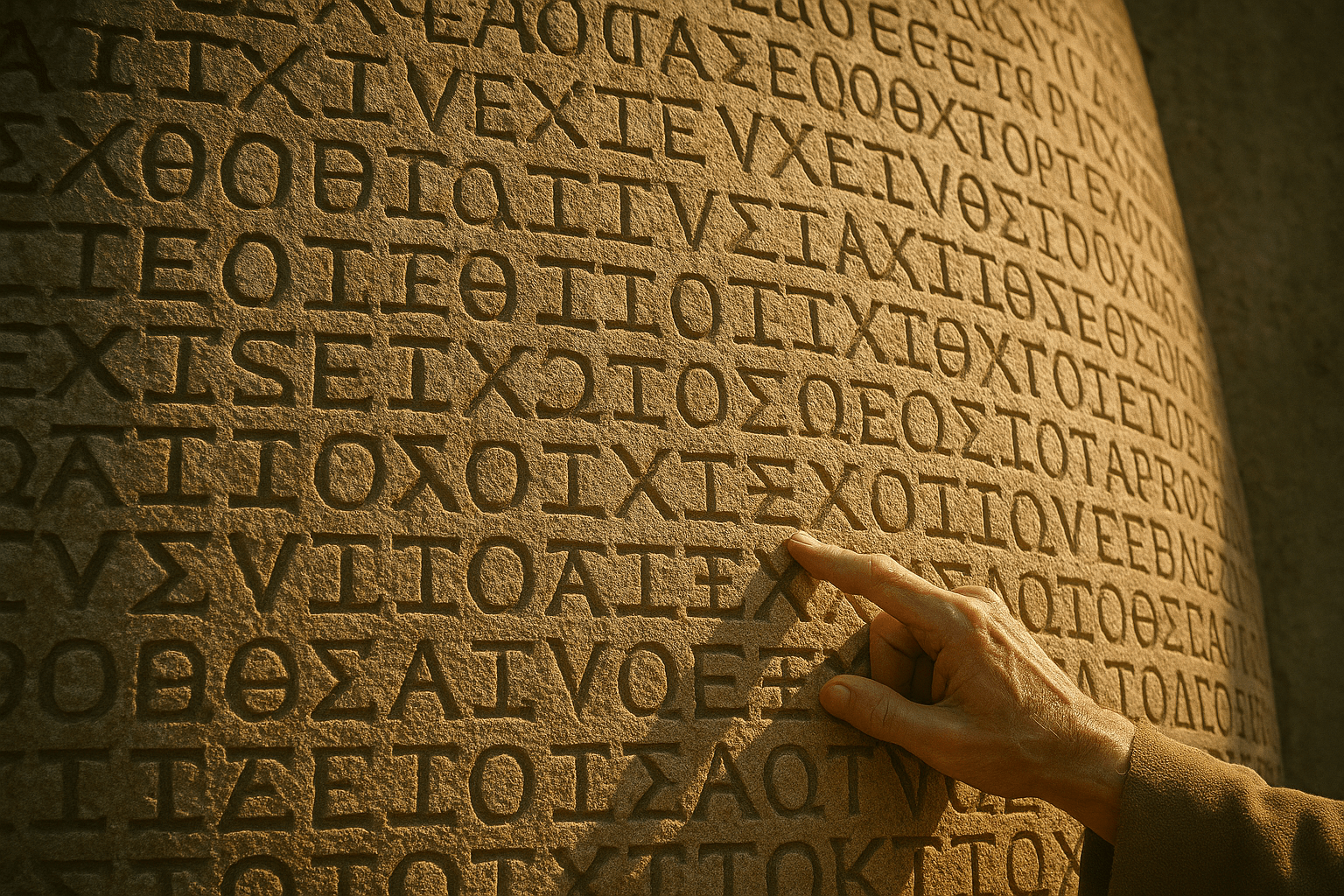

Imagine wandering through the ruins of an ancient city on the island of Crete. Among the weathered stones and olive trees, you come across a curved wall, twelve massive stone blocks covered from top to bottom with intricate carvings. This isn’t decorative art; it’s a legal document. You’re looking at the Gortyn Code, the oldest and most complete code of law ever discovered in Europe, a stone-etched window into a society that vanished over two and a half millennia ago.

Dating back to approximately 450 BCE, the Great Code of Gortyn is a monumental inscription that once adorned a public space, possibly the city’s agora (marketplace) or a courthouse. Unlike the systematic and abstract legal philosophies we might expect, the Gortyn Code is astonishingly specific, practical, and deeply concerned with the everyday lives of its people. It’s not a constitution of high-minded ideals, but a rulebook for real-life disputes.

Written in Stone, For All to See

One of the most fascinating aspects of the code is its physical form. The text is written in an archaic Cretan Doric dialect and inscribed in a style known as boustrophedon. This literally means “as the ox turns” when plowing a field. The lines of text alternate direction: one line reads right to left, the next left to right, and so on. This public display was a radical concept. It meant that law was no longer the exclusive knowledge of priests or aristocrats, whispered in secret chambers. It was a fixed, public record, accessible to any literate citizen.

This act of monumental inscription represents a crucial step towards the rule of law. It implies that justice should be consistent, transparent, and based on written statutes rather than the whims of a powerful individual. The code begins not with a divine proclamation but with a simple, direct command: “Whosoever may be minded to contend in law about a freeman or a slave, shall not seize him before trial.” From its very first sentence, the code establishes a core principle: due process.

A Society of Status: Freemen, Serfs, and Slaves

The Gortyn Code paints a vivid picture of a rigidly stratified society. Justice was not blind; it depended heavily on your social standing. The laws meticulously differentiate between three main classes: freemen (the citizen class), voikeus (a class of rural serfs tied to the land), and slaves. The penalty for a crime varied dramatically based on the status of both the perpetrator and the victim.

Take the crime of rape, for example. The code sets out a detailed schedule of fines:

- The rape of a free man or woman incurred a fine of 100 staters (a silver coin).

- The rape of an apetairos (a lower-class freeman) incurred a fine of 10 staters.

- If a slave raped a free man or woman, the fine was double (200 staters).

- If a free man raped a female serf (voikeus), the fine was a mere 5 staters.

While abhorrent to modern sensibilities, this sliding scale of fines reveals a society where social status was paramount. Yet, even within this strict hierarchy, the code contains surprises. Slaves, while considered property, were not without rights. They could own property of their own, enter into a legally recognized marriage, and pass their possessions on to their children. A slave’s testimony could even be considered in some legal cases, albeit under specific circumstances. This was a degree of legal personality unheard of in many other parts of the ancient world, including classical Athens.

Family, Divorce, and the Rights of Women

Perhaps the most progressive and detailed sections of the Gortyn Code deal with family law. The rules surrounding marriage, divorce, adoption, and inheritance are spelled out with incredible clarity, and they grant women a surprising degree of financial autonomy.

While men held primary authority, women had clear rights to property. A woman’s dowry remained her own property throughout the marriage. In the event of a divorce, the law was explicit: she was entitled to her entire dowry back, plus half of the household produce if the divorce was her husband’s fault. Furthermore, she could inherit property, and while sons inherited more than daughters, a daughter was still legally guaranteed a portion of her father’s estate.

Adultery was also addressed with financial penalties rather than corporal punishment. If a man was caught committing adultery with a free woman in her husband’s, father’s, or brother’s house, the fine was 100 staters. If he was caught with her elsewhere, the fine was halved. The law provided a mechanism for the cuckolded husband to detain the adulterer and publicly demand the fine, a form of institutionalized public shaming and financial retribution.

The Legacy of the Gortyn Code

The Gortyn Code is more than just a legal curiosity. It is a foundational document in the history of European law. It predates the famous Twelve Tables of Rome by a few years and provides our most complete insight into the legal framework of any Greek city-state. It shows us a society grappling with complex issues of justice, property, and personal rights, and attempting to solve them through a codified, public system.

The laws inscribed on that ancient wall reveal a world that is both alien and strangely familiar. We see a society obsessed with status and honor, yet also one that valued order, process, and the principle that disputes should be settled in a court, not by force. The men and women of Gortyn may be long gone, but their intricate, pragmatic, and surprisingly nuanced laws remain, etched in stone as a testament to their enduring quest for a just society.